Julius Jones: Oklahoma governor stops execution with last-minute decision for life sentence

Jones will instead get a life sentence without the possibility of parole

One hundred years ago, the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre broke out in Oklahoma, one of the worst acts of racist violence in US history, when a white lynch mob razed a prosperous section of Tulsa known as Black Wall Street and killed as many as three hundred people. One hundred years later, the state’s governor stopped an execution that criminal justice activists said would mark another “lynching” in the state.

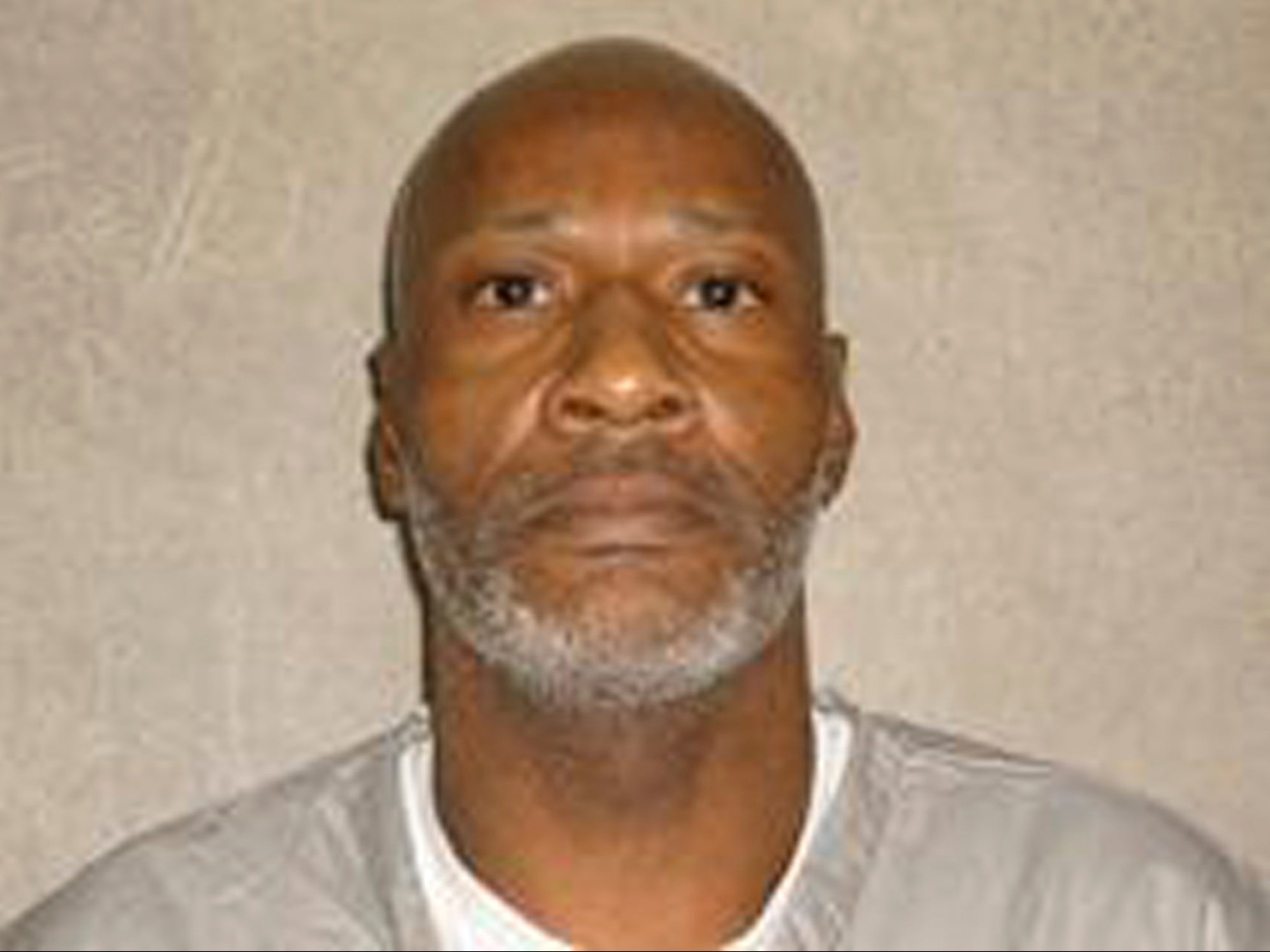

On Thursday, Oklahoma governor Kevin Stitt called off the execution of Julius Jones, a Black death row inmate who has long maintained his innocence in the 1999 murder that put him behind bars. The announcement came just hours before Jones was set to die by lethal injection.

“After prayerful consideration and reviewing materials presented by all sides of this case, I have determined to commute Julius Jones’ sentence to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole,” Governor Stitt said in a statement.

The Jones family, as well as supporters of the large “Justice for Julius” movement, were at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in the town of McAlester when they learned the news, the culmination of a two-decade campaign to free Julius.

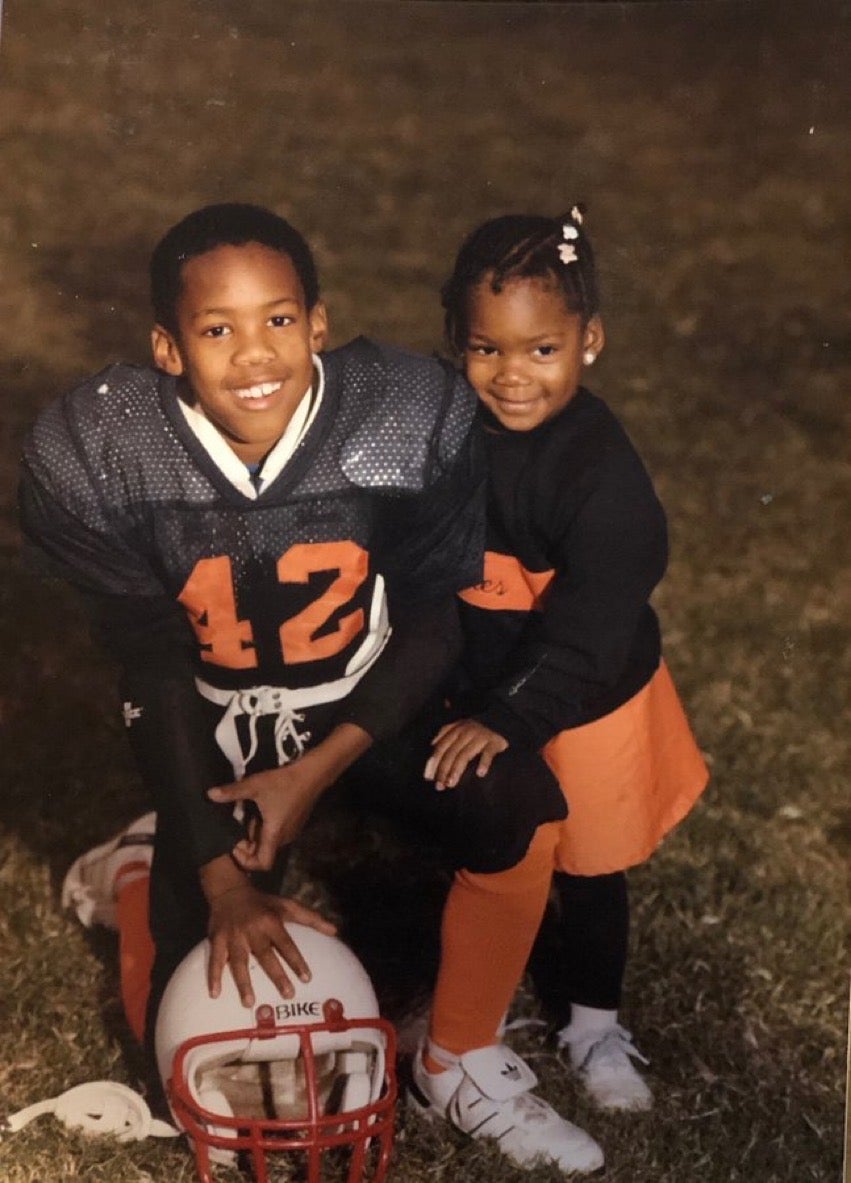

“I feel lighter, at peace. It’s not over,” Antoinette, Julius’s sister, told The Independent. “This is still just the beginning. The fight, we press on.”

She said that when her mother Madeline heard the announcement, she praised God.

“She did not want to see a lynching today,” Antoinette said, adding, ““I want to thank all the people around this country. It takes us all to save an innocent Black man’s life.”

Cheers erupted outside the prison and the Oklahoma state house, as well, where demonstrators had been holding vigils, trying to persuade Governor Stitt to stop the execution.

A nation divided

Jones was sentenced to death for the 1999 murder of businessman Paul Howell in the Oklahoma City suburbs, shocking the local community and traumatising Mr Howell’s sister and two young daughters, who witnessed the slaying up close. The case eventually became the centre of a nationwide debate about race, the death penalty, and fairness in the criminal justice system.

Supporters of the Justice for Julius movement range from Kim Kardashian to the European Union. They argue Jones never got a fair chance to clear his name, owing to what they saw as an ethically suspect police investigation, poor legal representation, and a state criminal justice system with a well documented bias against Black men, particularly when it come to the death penalty.

“People should care because we’re living in the era of George Floyd,” Justice for Julius activist Cece Davis-Jones told The Independent. “We saw in horror what happened to that man, how the system had its knee on George Floyd’s neck. We see now that the system has its knee on another man’s neck.”

The Howell family, as well a number of current and former Oklahoma law enforcement officials, have long maintained that Jones was rightly convicted, and had ample chances to prove his innocence already, in a review process that spanned two decades, 13 different judges, and proceedings at the state, federal, and US Supreme Court level. In their view, Jones is not another casualty to a racist system, but rather a man who has exploited the sympathy of celebrities and the public at large to cover up a horrific crime.

“We know Governor Stitt had a difficult decision to make,” the Howell family said in a statement on Thursday. “We take comfort that his decision affirmed the guilty of Julius Jones and that he shall not be eligible to apply for, or be considered for, a commutation, pardon, or parole for the remainder of his life.”

“Julius Jones forever changed our lives,” they added.

The murder of Paul Howell

On 28 July, 1999, Paul Howell, a 45-year-old insurance executive, spent the evening shopping for school supplies and getting ice cream with his young daughters, before returning to the wealthy, white Oklahoma City suburb of Edmond. As they pulled into Mr Howell’s parents’ house, a group of masked men approached, shooting Paul in the head and stealing his SUV.

Megan Tobey, Paul Howell’s sister, was the only eyewitness to the slaying, and said the shooter was a young Black man with a red bandanna, who had a few inches of hair coming out from under a skull cap.

The circumstances of the killing — a pair of urban Black youths accused of murdering a successful white man in a wealthy town, at the height of the “Tough on Crime” era — set off a panic in the Oklahoma City suburb of Edmond with arguably racist undertones. Officials were calling for the death penalty within days of the killing, well before the investigation had finished.

“The message behind this was, you were right to leave Oklahoma City and go to Edmond,” John Thompson, who taught Julius Jones in high school, told The Independent. “Because look, even the best of ‘em, can commit a crime.”

Police eventually singled out Jones, a 19-year-old university student at the time, as the one who pulled the trigger. They based their conclusion off of eyewitnesses who said they saw Jones driving the stolen SUV and confessing to the murder, as well as police searches which uncovered the murder weapon wrapped in a red bandanna at Jones’s home, later shown to contain Jones’s DNA. Jones also pleaded guilty to an armed carjacking that took place less than a week before Paul Howell was killed.

Yet the case was anything but straightforward.

The trial of Julius Jones

At trial, a pair of public defenders inexperienced in capital cases represented Jones, declining to call any witnesses on his behalf and advising him not to testify in his own defence, even though his family swore he was at home when the murder took place. This effectively consigned him to silence for the next 20 years without ever being able to share his side of the story in a court setting before his testimony at a clemency hearing this November.

(David McKenzie, Jones’s original trial lawyer, has said over the years he could have put on a stronger defence, but argued recently that the Jones family alibi was “completely bogus, false, and could not have been run for a bunch of reasons.” He told News 9 he declined to have them on the stand because “I needed his parents not to get up on the stand and lie.”)

Jurors, meanwhile, one of whom reportedly referred to Jones using the n-word, were never told that two of the state’s key witnesses were known criminal informants for Oklahoma police connected to the stolen car and drug trade, who were expecting benefits for their cooperation.

Oklahoma’s most important pieces of evidence, however, came from Chris Jordan. An acquaintance of Jones, Jordan made a deal with prosecutors and was sentenced to 30 years in prison rather than the death penalty, pleading that he had been an accomplice to the murder. Jordan said Jones was the one who killed Paul Howell, and had confessed to him, which he denies.

Jordan, however, was far from an unimpeachable witness. Detectives who interviewed him acknowledged he was erratic — contradicting himself on key facts like whether he heard gunshots, saw Mr Howell get killed, or touched the murder weapon. Right after the killing, Jordan asked to sleep over at Jones’s house for the first time. The Jones family alleges it was then that Jordan planted the murder weapon in Julius’s bedroom, which he denies.

On a deeper level, it seemed to some that even with these substantial questions in the case, the system in Oklahoma was incapable of delivering a just result. The murder of Paul Howell occurred during the tenure of Oklahoma County District Attorney Robert “Cowboy” Macy, a self-styled Wild West prosecutor who was one of the five most aggressive users of the death penalty in the country at the time. He called for the death penalty for Julius Jones within days of the killing.

Not that this bucked the norm: Oklahoma as a whole has conducted the most executions per capita in modern US history, has nearly the highest Black incarceration rate in the country, and has a disproportionate error rate when it comes to wrongfully convicting Black death row inmates. In Oklahoma, people charged with killing white men are nearly three times more likely to get the death penalty than those accused of killing nonwhite men, the Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission found.

All told, Jones’s attorneys said that stopping the execution, given all these doubts about the case, prevented the state from making “an irreparable mistake.”

“Governor Stitt took an important step today towards restoring public faith in the criminal justice system by ensuring that Oklahoma does not execute an innocent man,” said public defender Amanda Bass in a statement on Thursday.

Edmond police have pushed back on this framing of their work as racist and incomplete, noting that neither Jones nor his family chose to cooperate with police and share their story during the years leading up to the conviction. They argue the media and Justice for Julius backers have incorrectly tried to paint the suburb as a “sundown town,” a euphemism for white communities known to threaten Black people with violence.

“Citizens of Edmond were terrified, not because two young black males eventually were connected to the case, but because of the sheer randomness and the shocking and unnecessary nature of this crime,” Edmond police chief JD Younger wrote to Governor Stitt in October. “Race did not matter.”

Jones was convicted in 2002 and sentenced to death, and spent years fruitlessly trying to challenge his case, even as multiple men came forward to say they heard Mr Jordan confess to the murder in prison, which he denies. Nearly two decades after the murder, however, the flagging effort to overturn Jones’s death sentence took on a new life.

A growing movement

The Julius Jones case went beyond just a highly contentious legal process. It represented an unprecedented battle to win in the court of public opinion, with both sides using all the tools of the social media age to build support. They launched competing online movements, Justice for Paul Howell versus Justice for Julius, with supporting websites, social media pages, podcasts, and favourable interviews from their chosen experts and witnesses.

Julius Jones’s name may very well have been forgotten, had it not been for a widely seen 2018 true-crime documentary series on ABC called The Last Defense, produced by actor Viola Davis, which helped galvanize the Justice for Julius movement. The campaign now includes a surprisingly diverse range of high-profile supporters, including activist-minded liberal celebrities like Kim Kardashian and NBA star Steph Curry, as well as former Trump administration officials like Mercedes Schlapp and Republican Oklahoma lawmakers. It even reached diplomats at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and the EU, which both threw their weight behind calls to stop the execution.

In the era of Black Lives Matter, Julius Jones’s case became a key test of how much public sentiment, and political influence, really had been moved by years of activism and scholarship showing the extent of systemic racism in the criminal justice system. In the end, in one case in Oklahoma, it was enough to save a man’s life.

This fall, the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board recommended that Julius Jone be taken off death row and given a chance at parole, citing doubts about his case. It was the first time the board had done so in state history.

An agonising wait

Still, despite the historic ruling from the parole board, hope seemed to finally be running out for Julius this week.

“I’m empty inside. I feel invisible,” Madeline Davis-Jones, Julius’s mother, said on Wednesday, as the Jones family headed into its final visit with Julius in McAlester before the scheduled execution.

Jabee Williams, a friend of the Jones family and Justice for Julius activist, said he began to worry by Tuesday, when the governor still hadn’t made a decision on the execution, weeks after the parole board’s 1 November recommendation. In fact, he believes the governor wasn’t planning on stopping the execution at all, but eventually changed his mind after seeing the round-the-clock protests, public calls to action, and student walkouts that have surrounded the case in recent months. The governor’s office reportedly got 10,000 phone calls on Tuesday alone, temporarily crashing the phone system.

“I don’t think he planned on making that announcement,” Mr Williams said. “I think that because of the people of Oklahoma, because of the community support, because we showed our love for Julius Jones—Oklahoma wants Julius Jones alive. He had no choice but to do what he did.”

Even the governor’s own attorney general, John O’Connor, was vehemently against stopping the execution, saying he was “100 per cent certain” Jones was guilty earlier this week.

“I’ve reviewed the evidence three different times, looked at all the exhibits, and there’s no doubt in my mind,” the attorney general told KOCO on Tuesday.

But it seemed, after 20 years of sustained community activism for Julius Jones, that the governor started to have just enough doubts in his. Not enough, however, to set Julius free. Quite the opposite.

What happens to Julius Jones now?

The official order halting the execution stipulates that Jones “shall never again be eligible to apply for, be considered for, or receive any additional commutation, pardon, or parole.” In other words, his death sentence is now a life sentence.

However, death penalty experts like capital punishment activist Sister Helen Prejean say Jones will still be able to seek exoneration through the court system, if he can prove he was wrongly convicted in the first place.

“While Julius Jones’s death sentence was commuted to life without parole on condition that he can never again apply for a pardon or commutation, this does not preclude Julius from pursuing legal exoneration in state or federal courts,” she wrote on Twitter on Thursday.

As The Independent has reported, numerous people on death row have been wrongly convicted and later exonerated, though it would be a tough climb for Jones to prove his alleged innocence after so many years.

More immediately, the governor’s decision will also likely mean Jones is moved off of the state’s death row, home to some of its most restrictive prison conditions, and allowed to rejoin the general prison population.

There, he’ll be able to touch his family during visitation for the first time in two decades, supporters say.“He hasn’t touched his mom in over 22 years. He hasn’t hugged his sister. “That’s terrifying, you know?” said Mr Williams, the Justice for Julius activist. “You can’t put that into words, a mother not being able to touch her child.”

The next major battle over the Oklahoma death penalty

In the meantime, the controversy over the death penalty in Oklahoma isn’t going anywhere.

In October, the state executed John Marion Grant, its first execution in six years after a series of botched killings inspired a lengthy moratorium. Though officials insisted they strengthened their safety protocols, Grant writhed on the execution table and vomited before going unconscious, and execution observers have said the state’s policy amounts to “torture and human experimentation.”

A number of Oklahoma inmates have challenged the state’s lethal injection process as unconstitutionally cruel, but the conservative-leaning US Supreme Court has intervened to allow executions to go forward against some of the men anyway, despite a forthcoming federal trial on the question in February of next year.

On Wednesday, as Governor Stitt mulled Julius Jones’s execution, the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board recommended for the second time in its history that a death row inmate be granted clemency. Unlike with Julius Jones, the board said they didn’t have questions about Bigler Jobe Stouffer II’s guilt in a 1985 shooting, but rather they had questions about the Oklahoma death penalty system as a whole.

Board member Larry Morris said he was “dumbfounded” executions had resumed, despite the ongoing lawsuit and the apparent suffering John Grant experienced in the death chamber.

“It has to do with the drug cocktail, and whether or not it works, and whether or not it exposes an inmate to cruel and unusual punishment,” Mr Morris said of his decision.

Whatever a court ultimately decides, the Julius Jones case helped convince thousands of people around the world to question that underlying fairness of the Oklahoma death penalty in the first place, a feat nearly as unprecedented as bringing a man back from the brink of execution.

The Independent and the nonprofit Responsible Business Initiative for Justice (RBIJ) have launched a joint campaign calling for an end to death penalty in the US. The RBIJ has attracted more than 150 well-known signatories to their Business Leaders Declaration Against the Death Penalty - with The Independent as the latest on the list. We join high-profile executives like Ariana Huffington, Facebook’s Sheryl Sandberg, and Virgin Group founder Sir Richard Branson as part of this initiative and are making a pledge to highlight the injustices of the death penalty in our coverage.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks