Boy who shot abusive neo-Nazi father will not be given chance to appeal conviction

Joseph Hall, who was only 10 and suffered learning difficulties, gave up his Miranda rights during police questioning

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.An abused and troubled California boy who, under police interrogation, confessed to killing his neo-Nazi father, lost in a bid to overturn his conviction.

On Monday, the US Supreme Court decided it would not hear the case of Joseph Hall.

The decision was met with dismay from child advocates who argued that the then-10-year-old boy who shot and killed his abusive father in 2011 could not have realized the wrongfulness of his actions.

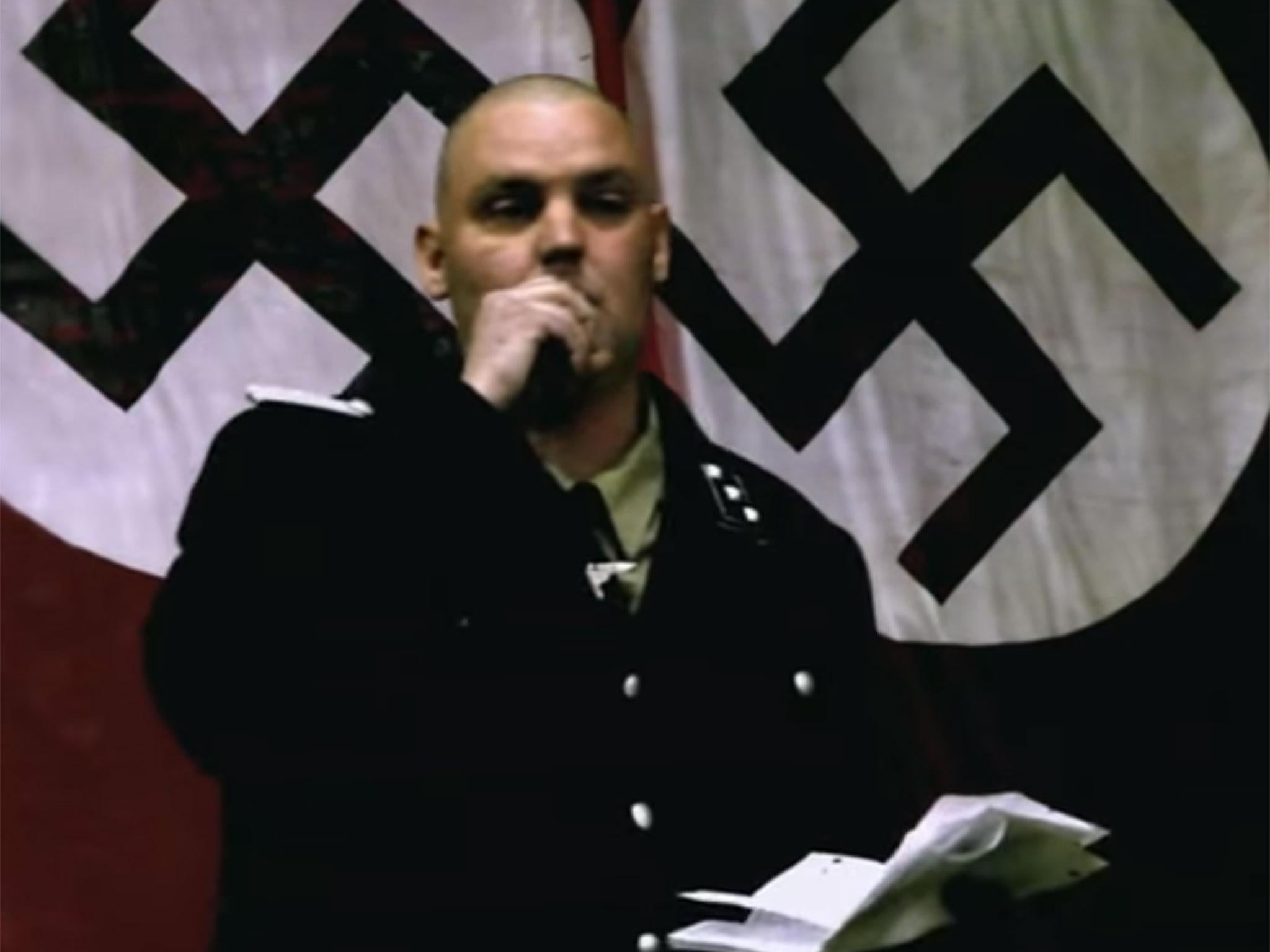

Joseph was convicted in 2013 of second-degree murder in the killing of his father, Jeffrey Hall, a rising star among white supremacists. He was sentenced to 10 years in a California juvenile facility and will be 23 by the time he’s released.

At the heart of Joseph’s case was his decision to give up his Miranda rights while being interrogated by a police officer. His supporters argue that Joseph, now 15, has developmental disabilities and could not have understood what that meant.

Child advocates, as well as Joseph’s legal team, believe the Supreme Court’s decision leaves unaddressed an issue that affects children interrogated by police officers.

“We are obviously disappointed that the Supreme Court denied Joseph’s petition, which presented important questions that are worthy of review,” his attorney, Nima Mohebbi, said in a statement. “We believe the notion that any ten-year-old can understand and intelligently waive his or her Miranda rights in a coercive police interrogation is nonsensical.”

Hall, then a budding leader of the largest neo-Nazi organization in the country, was shot at point-blank range while asleep on his living room couch at his home in Riverside, California. Joseph, according to court records, took his father’s revolver from the upstairs bedroom where his stepmother was sleeping. He fired a bullet into his father’s head, just behind the left ear.

“I shot dad,” the boy told his stepmother.

During the interrogation, a Riverside police detective recited each sentence of the Miranda warning and asked Joseph whether he understood. The officer had to correct him and explain to him what the sentences meant. For instance, the boy thought that “you have the right to remain silent” meant he had “the right to stay calm,” according to court records.

The boy’s statements to authorities also suggested that he didn’t comprehend that his actions had lasting consequences, not only for his father but also for him.

For instance, after police officers arrived at the crime scene during the early morning hours of 1 May 2011, he asked: “How many lives do people usually get?”

When he was taken to juvenile hall, staff had to buy him a pair of tennis shoes because the facility didn’t have anything small enough to fit him. Mike Soccio, a former Riverside County chief deputy district attorney who handled Joseph’s case at that time, told CBS News in 2011 that the boy asked whether he’d be able to keep the shoes when he goes home.

Joseph’s legal team petitioned for the Supreme Court to review the case after his appeal was denied by the California appellate courts, which found that he was not coerced into talking or confessing to police, that he understood the wrongfulness of his actions and that he comprehended what giving up his Miranda rights meant.

The California attorney general’s office agreed, arguing in court records that Joseph told police he shot his father even without being asked. The agency also argued that the issues raised in Joseph’s petition to the Supreme Court “would be better addressed to state legislatures.”

A spokeswoman for the attorney general’s office declined to comment further.

Frank Vandervort, president of the American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children, said the California courts’ findings have “no basis in science,” citing bodies of research on children’s brain development.

“The California court is just abjectly wrong about that,” he said.

Marsha Levick, co-founder of the Juvenile Law Center, said that although the Supreme Court’s decision was not surprising, it was dismaying.

“It’s unfortunate. He’s so young,” Ms Levick said. “We’re talking about a 10-year-old. It’s not difficult to understand what seems absurd about what happened here.”

Child advocates and Joseph’s legal team also point to the abuse that the boy endured in his family’s home. Court records say Jeffrey Hall, the National Socialist Movement’s regional director for the Southwestern states, was addicted to methamphetamine and punished his son every day for being too loud or for getting in his way - sometimes punching and kicking him several times in the back.

The night before he was killed, Hall, an unemployed plumber who used to patrol the US-Mexico border looking for illegal immigrants, threatened to remove all the smoke detectors and burn the house down while his family slept, court records say.

Joseph, whose exposure to alcohol and drugs began in the womb and who bore the brunt of his father’s violent outbursts, had pervasive attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and low-average intelligence, court records say. At school, he was often unable to sit still and threw violent tantrums at his classmates and teachers. By the time he was 10, he’d attended six schools.

Adding to child advocates’ disappointment was a recent decision by California Governor Jerry Brown to veto a bill inspired by his case.

SB 1052, which would not have had any effect on the case, would have required those younger than 18 to first consult with an attorney or a legal guardian before waiving their Miranda rights and before being interrogated by a police officer.

In his veto message Friday, Mr Brown said that juveniles are more vulnerable than adults to succumb to pressure from police officers to talk and are more likely to confess to crimes they didn’t commit. Still, investigators solve countless serious crimes through questioning, Brown said, adding that he’s not prepared to sign SB 1052 into law without fully understanding its ramifications.

He noted, however, that he plans to continue to work with the legislature “to fashion reforms that protect public safety and constitutional rights.”

Senator Holly Mitchell, the bill’s co-author, said that giving someone access to an attorney doesn’t mean the interrogation won’t go forward and that guilty parties won’t be identified.

“The point of this bill was to acknowledge and recognize that kids don’t often understand the complexity of waiving your rights,” Ms Mitchell said. “The law should not treat them as pint-size adults. When we know better, we should do better.”

In 2011, the Supreme Court ruled that a police officer must take a juvenile suspect’s age into consideration when deciding whether to issue a Miranda warning. But Mr Vandervort said there is no federal law, either through legislation or court ruling, that requires children under a certain age to first talk to an attorney before they waive their Miranda rights.

Rules also vary among states.

In Iowa, Montana and Connecticut, children under 16 must first consult with an attorney before they’re interrogated. In Kansas, the age limit is 14. In Indiana, a legal guardian or an attorney must consent to the Miranda waiver.

Joseph’s supporters believe the issue of Miranda waivers in juvenile interrogations is not uncommon and will come up again. They said the Supreme Court, at some point, will have to tackle it.

“There will be other opportunities,” Ms Levick said. “We will just have to continue to challenge the admission of the statements when they’re obtained under these circumstances.”

Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments