Jonestown Massacre: How 918 people followed a cult leader to Guyana, 'drank the Kool-Aid'... and died in a single day

Believers of the Peoples Temple of the Disciples of Christ followed Reverend Jim Jones to Guyana in the Seventies, hoping to create a utopia in the jungle

As the helicopters flew the first journalists in, the stench hit them when they were still at 300ft.

From that height, the piles of dead bodies looked to one reporter just like “a garbage dump, where someone had dumped a lot of rag dolls”, dressed in cheery shades of red, green or blue: “bright, happy colours”.

On the ground, as they clutched handkerchiefs to shield their noses from the smell, the reporters could see how the bright, happy clothes were all that was holding many of the corpses together.

The bodies had decomposed badly in the jungle heat of Guyana, where a year earlier these people had come to carve out a new, better world: Jonestown.

Now, forty years on, a new documentary recalls what would culminate in the largest loss of American lives in a single event until 9/11.

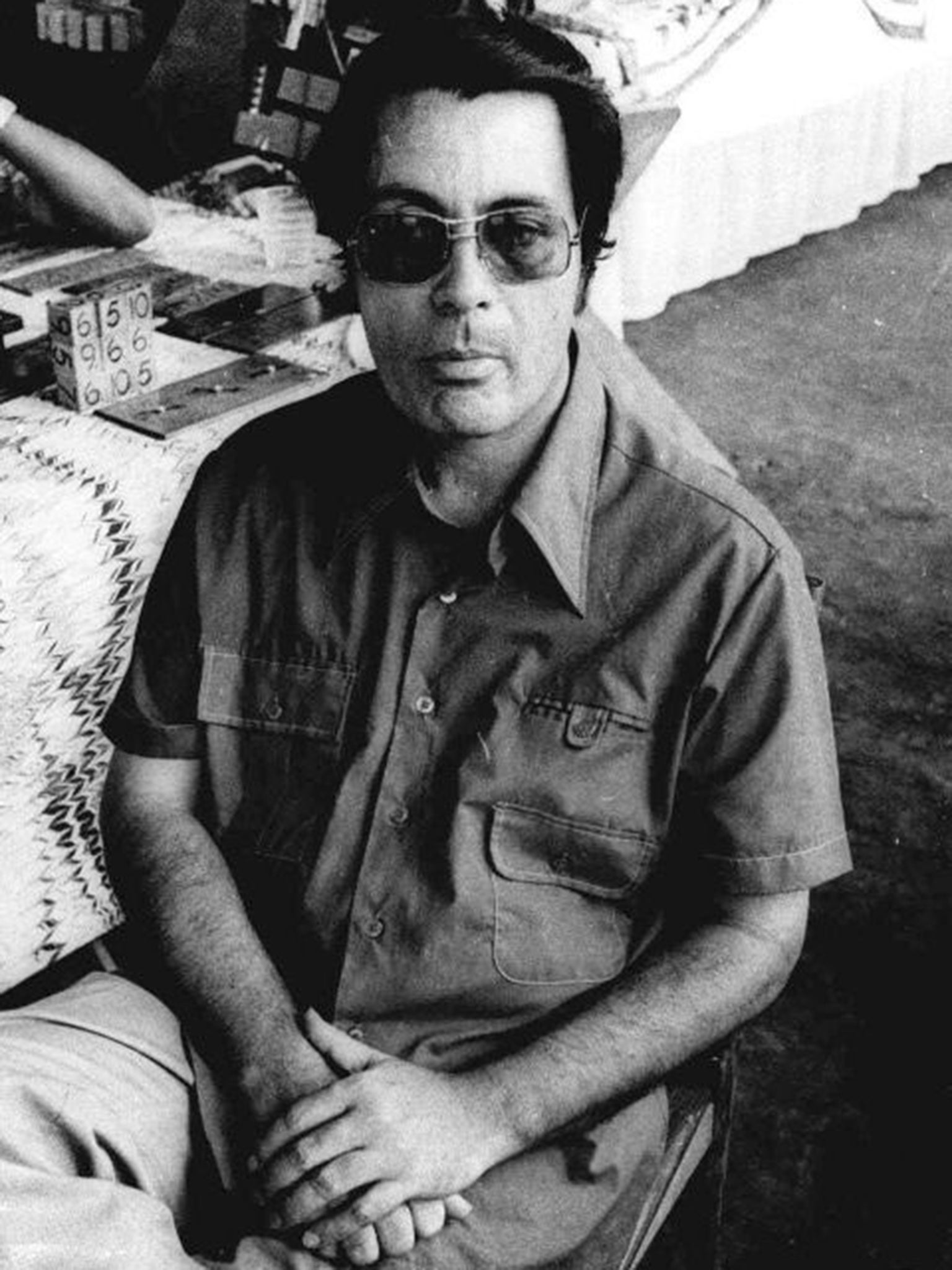

Named after their leader, the Reverend Jim Jones, founder of the Peoples Temple of the Disciples of Christ, Jonestown was envisaged as a “rainbow family” of all ages and races, working towards the utopia the preacher had promised them: “Divine principles. Total equality. A society where people own all things in common, where there is no rich or poor, where there are no races.”

Here, good old-fashioned Pentecostal preaching would be fused with the revolutionary ideals of the Sixties and Seventies.

Here, the walls would be daubed with signs proclaiming: “Love one another.”

And here, a guard tower would loom above the cottages of the disciples. That too would have bright, happy colours: pretty seascapes painted to go with the children’s slides that were installed at the bottom of the structure.

And the guard tower would be called “the playground”.

When they finally counted the bodies after what would become known as the Jonestown massacre of 18 November 1978, the total came to 918, of whom 304 were children. They had been persuaded to “drink the Kool-Aid”.

Although in fact, the Jonestown community preferred a cheaper alternative – Flavor Aid – and used it to mask the bitter taste of cyanide, mixed with a dash of Valium.

Jones got his disciples to poison their children first – once they had seen their kids die, what would the adults have to live for?

The “deranged preacher”, as the press called him, wanted to create a glorious sacrifice, a defiant act of “revolutionary suicide” that would echo through history.

Some disciples willingly colluded, cheering as he exhorted them to kill themselves and their children.

But the bodies found with bent needles in their arms testified to the fact that some refused to “drink the Kool-Aid”, and were forcibly injected.

Today, after four decades, the South American jungle seems to have reclaimed Jonestown. When one survivor visited in the late Nineties, he found only the large vat from which those died had taken the poisoned Flavor Aid.

Jones’s legacy, you might think, is just an expression about drinking the Kool-Aid, deriding – not celebrating – a failure to question mass delusion.

But now the airing of a new documentary about the massacre has raised questions about whether it could all happen again.

Leslie Wagner-Wilson, a survivor who contributed to the A&E documentary Jonestown: The Women Behind the Massacre, has warned: “I think Peoples Temple rose from a social political environment that’s similar to what we’re facing now.”

Ms Wagner-Wilson, now a 61-year-old grandmother, told Fox News: “There’s a need. People want to be a part of something. They want to feel safe; they want to feel a sense of community.

“There are still folks out there and they are running under the guise of religious organisations. I just want people to be careful. I want Jonestown to be a lesson.”

Amid all the soul-searching that followed what one of those first newsmen called “this mind-boggling, nihilistic thing”, one columnist insisted: “The real culprit is the institution that America has become.”

A little grandiose, perhaps, but Rev Jones’s Peoples Temple was certainly born from some of the tensions within American society.

The son of an alcoholic father, growing up in a shack without plumbing during the Great Depression, Jones came to sympathise with the downtrodden, attending Communist Party meetings and clashing with his Ku Klux Klan-supporting father on the issue of race.

His movement started off in the Cadle Tabernacle, Indianapolis, in 1956, initially using a faith-healing evangelist preacher to draw in the crowds.

Soon his message of social justice and racial integration meant Jones didn’t need sidekicks.

He was doing something radically different. When he adopted a black boy and gave him his own name, Jim Jones Jr became the first African-American child adopted by a Caucasian family in the state of Indiana.

According to one newspaper, Jones offered his mainly black congregation “opportunities in social justice activism” that were available nowhere else. The Temple fed pensioners, taught students, and took bus trips to spread the word.

A fair few who answered the call were people with addictions, and their families. The Temple seemed to work where all others failed. There was soon no shortage of people asking for help.

“This was the late Sixites, during the love and peace movement,” recalled Ms Wagner-Wilson, who joined with her family in her early teens. “A lot of drugs, which my sister Michelle became involved in: acid, LSD.

“My mother was told about an organisation, People’s Temple, that had a great drug rehab programme.”

And once in the Temple, they relished the idealism. “I felt like I was going to make a difference in the world,” said Ms Wagner-Wilson. “I loved it.”

The local politicians loved it too, at first.

In 1975, Temple members campaigned to help get Democrat George Moscone elected San Francisco mayor. In 1976, Moscone appointed Jones to the San Francisco Housing Commission.

But the increasingly strange behaviour of Jones began to exert a malign influence.

He was becoming addicted to prescription drugs. He seemed genuinely to believe he was the only heterosexual man on Earth.

“He would always tout his sexual prowess and talk about how men were homosexuals,” recalled Ms Wagner-Wilson. “He treated the women better, but he was very manipulative and would try to separate families and destroy marriages, which would give him more power.”

By the age of 15, she was starting to have her doubts about The Temple. Leaving, though, was much harder than joining.

“We thought Jim could read our minds,” said Ms Wagner-Wilson. “We were totally fooled.

“It just became very controlling. It wasn’t fun anymore.”

And all the time, Jones was convincing his followers to sell their homes and sign over their salaries to his movement. The press began asking questions.

In August 1977, New West magazine published an expose, using former disciples’ testimonies to build up a picture of fake healings and real humiliations, of beatings and financial impropriety.

Jones tried and failed to use his local political influence to kill the story. And then he took his flock to Jonestown.

For followers like 17-year-old Jim Jones Jr, this really was going to be a new and better world.

“We had an organisational structure,” the preacher’s adopted son told Oprah Winfrey in 2010, “An agricultural team, education projects, the infirmary. It was a whole community.”

But where revolutionary idealism leads, control often follows.

And these were harsh conditions in which to build a revolutionary utopia. As they got harsher, so did Jones’s paranoid cruelty.

Anyone complaining about maggots in the rice risked a beating, because moaning about the food made you a traitor in league with the CIA.

After piecing together the testimony of Jonestown survivors, Tim Cahill of Rolling Stone magazine reported that Jones had become convinced the poor quality rice was the work of the CIA, which was trying to sabotage his great sociopolitical experiment.

Jones, the paranoid father figure, instructed his flock to inform on each other. Children told on their parents. Mothers and fathers betrayed their children.

Escape from the camp complex was impossible. The armed guards of the Temple security squad patrolled the exit trails. The watchtower “playground” was erected. Those who did try to escape were taken to the “Extra Care Unit”.

Here, Cahill wrote, the “patients” were drugged senseless. They emerged “unable to carry on a conversation, their faces blank, as if they had been temporarily lobotomised”.

After building up a picture of a day in the life of a Jonestown resident, Cahill outlined something similar to the routine of a labour camp.

To help you “learn” in your sleep, the public address system was sometimes kept on all night.

You were woken at 6am for a breakfast of rice, watery milk and brown sugar. Then you were sent to labour in the fields in tropical heat, for more than 10 hours.

In the evening, the public address system would again start blasting out “the news”.

After dinner of rice, gravy and wild greens, it was time for Russian language lessons – because the Soviet Union was a “paradise on earth” whose leadership “helped liberation movements.”

About three times a week, there would be a “Peoples Forum”. Seated on his “throne”, Jones would instruct and punish his flock, sometimes until about 3am.

Then his undernourished people would snatch three hours of sleep before it all started again.

In his wooden house, slightly larger than all the others, Jones read about Marxism, conspiracies and media manipulation. He complained of suffering from insomnia, mini-strokes, temporary blindness and convulsions. His medicine cabinet was filled with Valium tablets and synthetic morphine.

Why did no one resist him?

In Jones’s lair, Cahill found letter after letter addressed to “Dad”. He seems to have encouraged his disciples to engage in “self-analysis”, providing him with lengthy, written confessions of their every vulnerability

The letters spoke of total submission to Jones, and burning hatred for the California-based “defectors” who had left the movement and betrayed it to those pursuing a “rightist vendetta” against the Temple.

“I would like to have them all in a room together and take a gun and spray the row of them” wrote one 89-year-old woman. “I am glad to have a Dad and Father like you.”

In an environment like this, Ms Wagner-Wilson has now warned, you might think there’s something wrong, “but because everyone else is embracing it and clapping and being joyous, you look at yourself and say, ‘It must be me’”.

The end came when the California Democrat Congressman Leo Ryan flew to Guyana to investigate the complaints he had heard about the Temple.

On 17 November he arrived at Jonestown with a delegation of news reporters and representatives of the Concerned Relatives, a group formed by US-based defectors and anxious family members of Jonestown residents.

When the delegation left the following afternoon, they took with them 16 Jonestown residents who had implored the congressman to take them with him.

They got as far as the Port Kaituma airstrip, six miles from Jonestown, before they were ambushed.

Larry Layton, one of those who had asked to leave, revealed himself as an undercover Jones loyalist by pulling out a handgun and opening fire.

At the same time, a posse of Temple security men arrived in a tractor.

Congressman Ryan was shot more than 20 times. Patricia Parks, one of the 15 genuine Jonestown refugees, was among the dead.

Meanwhile back at Jonestown, Jim Jones had gathered his people together in the pavilion.

“How very much I loved you,” he told them. “How very much I tried to give you a good life.”

Of those who began 18 November 1978 in Jonestown, and who didn’t leave with Congressman Ryan, only 20 survived.

Two had the luck to be sent by the leadership to get food in the early morning. Three were told to go to the Russian embassy in Guyana’s capital Georgetown, carrying a suitcase full of $550,000 in cash and letters leaving all the Temple’s assets – totalling more than $7.3m (£5.3m) – to the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

Leslie Wagner-Wilson, then 22, was one of a tiny group of adults who had sensed that something very bad was about to happen. In the early hours of 18 November they slipped away from Jonestown, a desperate party of seven adults and four children. The youngest was Ms Wagner-Wilson’s three-year-old son Jakari.

She strapped him to her back, and with the others trekked more than 30 miles to the safety of the small town of Matthew’s Ridge. Ms Wagner-Wilson lived to tell her tale in her book Slavery of Faith.

Her husband, mother, sister, brother, niece and nephew drank the Flavor Aid.

Remarkably, after the massacre, an audio tape was discovered of the final meeting in the pavilion. On it, the occasional cries of the babies can be heard. The presence of the armed guards with semiautomatics, shotguns, pistols and crossbows cannot.

In folksy tones of sweet reasonableness, Jones rails against the defectors who “committed the betrayal of the century”.

He tells his people the departure of the Ryan delegation is only the start of it: “They won’t leave us alone. They are now going back to tell more lies, which means more congressman. There’s no way, no way we can survive.”

“My opinion,” says Jones, “is that we be kind to children and be kind to seniors and take the potion like they used to take in Ancient Greece, and step over quietly. Because we are not committing suicide. It’s a revolutionary act.”

One elderly woman did dare to dissent. “What about going to Russia?” she asked.

“It’s too late for that,” said Jones.

“But,” the woman persisted, “I look at all the babies and I think they deserve to live.”

“I agree,” said the preacher. “But what’s more, they deserve peace.”

The Guyanese Defence Forces were coming, he said, to shoot and torture them. There was no time to lose.

“Please get us the medication,” urged Jones. “It’s simple. There’s no convulsions with it. Don’t be afraid to die.”

One woman, thought to be Jones’s loyal mistress Maria Katsaris, reinforced the words of “The Father”.

“There’s nothing to worry about,” she said, “Everybody keep calm ... and the oldest children can help love the little children and reassure them. They’re not crying from pain. It’s just a little bitter tasting but, they’re not crying out of any pain.”

But there were convulsions, the cyanide filling mouths with saliva, blood and vomit.

Some mothers still willingly took their children to the vat of poison, before drinking from it themselves. Other infants were snatched from the arms of wavering mothers. Parents and grandparents began to sob hysterically as they watched the children die.

But one follower took the microphone to assure his fellow disciples: “The way the children are, laying dead now, I’d rather see them lay like that than to see them have to die like the Jews did, which was pitiful.

“And the ones they take captive, they’re gonna just let them grow up and be dummies like they want them to be, and not socialist like the one and only Jim Jones… Thank you Dad.”

They gave him a round of applause.

As the babies screamed in the background, Jones admonished the faithful: “Die with respect, die with a degree of dignity. Stop this hysterics … This is not the way for people who are socialistic communists to die. We must die with some dignity.”

“That’s right,” said one follower.

Odell Rhodes, though, had seen enough. The Vietnam vet and former addict had been trying to find a way out of Jonestown for weeks.

Now, as he would later tell Tim Cahill of Rolling Stone, he was having to hold children as they died in his arms.

He heard one of the camp medical staff ask for a stethoscope. He fell in behind the nurse as she went to fetch it.

When the armed guards challenged them, the nurse answered, “We’re going to the medical office.”

Rhodes became one of only four people to survive being in Jonestown when the mass murder-suicide started.

Stanley Clayton, 25, watched a man convulsing as the poison took hold. Everyone who took the poison, he realised, died suffering. He slipped away.

The third survivor, Grover Davis, 79, hid in a ditch. He just didn’t want to die, he said, “[But] I didn’t hear nobody else say they weren’t willing.”

The fourth survivor probably had the most incredible escape of all. In the commotion of everyone being summoned to the pavilion, 76-year-old Hyacinth Thrash feared mercenaries might be coming to terrorise the camp and hid under her bed.

At first she waited for her sister and other housemates to return from the pavilion. Then she fell asleep.

Hyacinth awoke the next morning to find the camp strewn with the bodies of those who had been taken out of the pavilion to die face down on the ground.

Jones himself didn’t “drink the Kool-Aid”. They found the 47-year-old preacher with a bullet wound to the head: possibly murder, perhaps more likely suicide.

But to the very end he encouraged others to drink the poison.

It is his voice that can be heard at the close of what has become known as “the death tape”.

“Some people assure these children of … stepping over to the next plane,” Jones commands.

“We didn’t commit suicide,” he insists. “We committed an act of revolutionary suicide protesting the conditions of an inhumane world.”

From somewhere comes the sound of organ music, the strains of We Shall Overcome. Then there is nothing, just the hissing static of the tape.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks