Joe Kennedy: How Christian conservatives made a hero of a high school football coach

Case being considered by US Supreme Court among several likely to make history break with precedent, writes Andrew Buncombe

According to Joe Kennedy, he wants nothing more than to get his job back and return to coaching high school football.

The last thing on his mind, according to his lawyers, is to be associated with a ground-breaking case that could in its own way, be as historic as Roe v Wade, or the overturning of that 1973 judgement.

Is he not trying to be a legal or religious martyr?

“Coach?!” says lawyer Hiram Sasser, a note of bemusement in his voice.

“You’ve heard the [New York Times] podcast. That’s coach. He’s a simple guy. He just wants his job back.”

Others disagree.

They say whether or not the 53-year-old who served 20 years in the Marines, before finding God, initially intended his dispute with the Washington State school district that hired him to turn into something bigger, that is what has happened.

Backed by powerful groups and individuals, conservative Christians hope that Kennedy’s case will succeed in pushing back prohibitions on the separation of religion and state.

In that sense, they hope to emulate that anti-choice activists who appear set to end the right to legal abortion, with the court’s imminent decision over a state’s restrictions in Mississippi.

As soon as the issue started to receive national attention, figures such as former Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee, who often tapped into the support of evangelicals, said the decision to suspend Kennedy had been a “classic example of overreach” by local government.

“The Supreme Court’s going to have to find its spine,” he said in 2019, when the court initially decided not to consider his case. “They need to clarify once and for all that the First Amendment is real and that it means something.”

The court had then decided not to pick up the case after a lower court declined to reinstate the coach.

Kennedy tried again, and a three-judge panel of the 9th Circuit ruled in March 2021 the school district's efforts to prevent Kennedy from praying did not violate his constitutional rights, and his post-game speech on the field was speech as a government employee.

“At issue in this case is not, as Kennedy attempts to gloss it, a personal and private exercise of faith,” said judge Judge Milan Smith.

“At issue was – in every sense of the word – a demonstration, and, because Kennedy demanded that it take place immediately after the final whistle, it was a demonstration necessarily directed at students and the attending public.”

When the full appeals court refused to reexamine the case, Kennedy appealed again to the Supreme Court, claiming he had “lost his job as a football coach at a public high school because he knelt and said a quiet prayer by himself at midfield after the game ended”.

In January 2022, the nation’s highest court said it would hear the case, adding another high-profile case to its docket. Already this summer, the court is set to rule on a case that could overturn Roe v Wade, and a leaked draft decision said at least five of the nine justices were set to overturn it.

Kennedy said he had a difficult childhood after growing up in Bremerton, a Naval town, and that he was in and out of the foster system.

“I was pretty much a loner growing up and always in trouble,” he told New York Times reporter Adam Liptak. “I jumped in and out of group homes and foster homes in this area.”

According to Kennedy, he was saved by a decision to join the Marines, where he spent 20 years.

“I needed to have that discipline. I needed to be able to belong to something.”

When he left the Marines he returned to Bremerton where he found religion, and says it helped him survive a crisis in his marriage. At that point, he says he started putting prayer front and centre of everything he did, including whether or not to take a part-time job as an assitant football coach at the city high school.

As he was trying to decide, he says he scrolled through his television channels and stumbled upon the 2006 movie Facing the Giants, directed by and staring Alex Kendrick, as a high school football coach who helps end its losing streak by praying before the games. He decided that he would do the same.

“God came down and just gut punched me and answered the question of, am I supposed to coach? Absolutely,” he told Liptak. “He might as well have just walked up and say, you know, here’s your whistle. Go play.”

Sasser says that when Kennedy took the job there was already a habit of someone saying prayers in the locker room before the team ran out.

“When he was taking the knee, some of the players – after several times – asked him ‘What are you doing out there’,” says Sasser. He says Kennedy told the he was praying and giving thanks.

He says that when they asked if they could join, he told them: “It’s a free country. You can do what you want”.

At that point, he was asked to lead the prayers inside the locker room. (The school district has said it was not aware of any such prayers.)

Indeed, it appears the prayers that the coach continued to pray on the touchline, usually at the 50-yard or half-way line, undisturbed for a number of years. Reports suggest that it was only when a visiting team’s coach later congratulated the Bremerton principal that the school felt it had to act.

Reports from the time in the Kitsap Sun and other local media suggest that initially some sort of compromise was reached. When that fell through, Kennedy informed reporters what had happened and said he would be praying as he always did, at the team’s next game.

Images from one or two games in October 2015, with Kennedy kneeling, surrounded his players, as well as members of the opposition and the general public, made national news.

“He has a right to be able to tell the media, this is his plan, and this is what he’s going to do,” says Sasser. “As his lawyer, I told the media, okay, well, he's going to go out and do his prayer, as he had originally done - alone - before.”

In November 2015, after Kennedy performed another another post-match, he was placed on administrative leave by the Bremerton School District and his contract was not renewed.

The school district and many in the community disagree with the narrative put forward by Kennedy and his lawyers.

They argue that the school went out of its way to find a compromise, that would respect his religious rights and allow him to pray privately, without it it being something that could be interpreted as school-led prayer.

Speaking as a private citizen, Jennifer Chamberlin, who represents Bremerton City Council’s District 1, says the case was important to her because she remembers growing up in Tennessee where she was member of the school marching band.

She says prayers were a regular part of the pre-game preparation, and as a young person trying to work out what she thought about religion, she found the pressure to conform very stifling.

She says she still remembers the fist time the team gathered for practice and a “very graphic” prayer about “the blood of Christ”, was said by a member of the band as the others stood to attention. She says she felt blindsided.

“Afterwards, I talked to my band director, and he just kind of shunned me and said, ‘Well, you don't have to do it if you don't want to’,” she says.

“And I talked to some other, you know, staff, people and my peers. And really got I got the cold shoulder.”

Chamberlin says the story Kennedy and his lawyers have presented is that none of the students were obliged to pray. Yet, she says she knows from her own experience at that age, that young people can be easily influenced, especially by someone like a sports coach.

“The narrative is that it's harmless. But there's a lot of things that are illegal to do when minors are involved, because they're impressionable,” she says. “There's a reason we have laws that protect children and students from religious coercion.”

She and others say that once Kennedy invited the media to watch him pray, it turned into a “fiasco” and she thinks he was putting his own interests above those of the children. In November 2015, his was placed on administrative leave and his contract was not renewed.

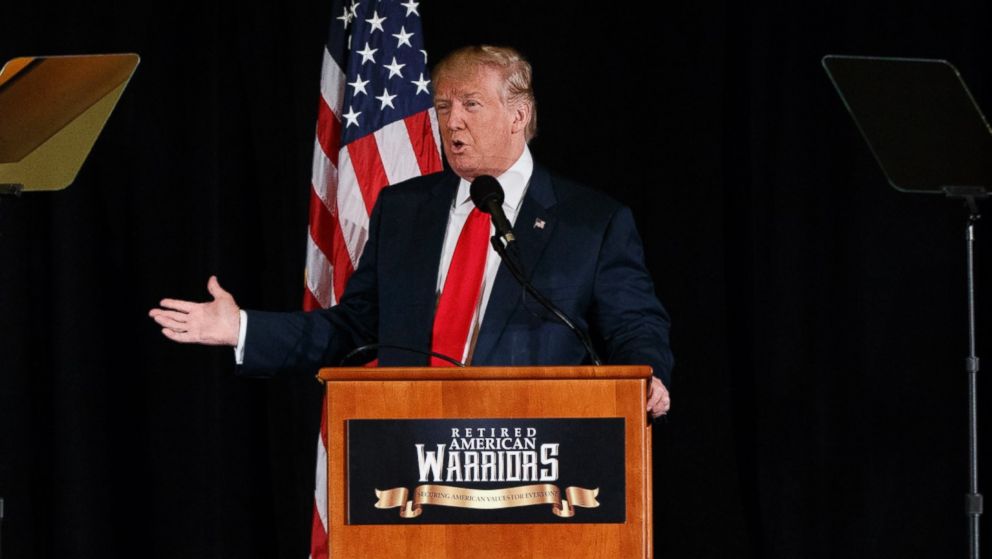

The year after he was let go, Kennedy attended an election campaign speech for veterans in Herndon, Virginia, held by Donald Trump, where the Republican candidate talked of his case and asked Kennedy to stand up.

“They put me on suspension and then at the end of the year, they gave me an adverse write-up of how w ell I did my job,” Kennedy told Trump.

Trump replied: “It’s absolutely outrageous. I think it's outrageous. I think it's very, very sad and outrageous.”

The soon to president’s comments helped ensure that Kennedy’s case was championed by religious conservatives and evangelicals, whose support he managed to tap into to help him secure the White House.

It also helped him ensure the support of groups such as First Liberty. Its CEO and founder Kelly Shackelford, said of the Kennedy case: “No teacher or coach should lose their job for simply expressing their faith while in public.”

He added: “By taking this important case, the Supreme Court can protect the right of every American to engage in private religious expression, including praying in public, without fear of punishment.”

Sasser says he will not predict how the court rules.

“We're hopeful. This is this is the last stop of this case, and we have a very small ask,” he says. “But there are nine justices, and they have their way of doing things, and so it's impossible for us to know what's going to happen until it happens.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks