‘I hoped it was a cruel joke’: Mother of James Foley describes torment of son’s public killing by Isis

Diane Foley found out about the death of her son in a phone call from a journalist

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The mother of an American journalist murdered by Isis told a court of her “incredible shock” at finding out about her son’s death in harrowing testimony.

Diane Foley, the mother of James Foley, was notified of his killing in a phone call from another journalist in August 2014, nearly two years after his kidnapping while on assignment in Syria.

“I didn’t believe it. It sounded too horrific,” she said. “I hoped it was a cruel joke.”

She sent messages to all of her government contacts seeking information, including the FBI and the State Department, but received no response. “It was an eerie silence,” she said.

Later that day, Barack Obama announced in a televised address to the country that Mr Foley had been beheaded.

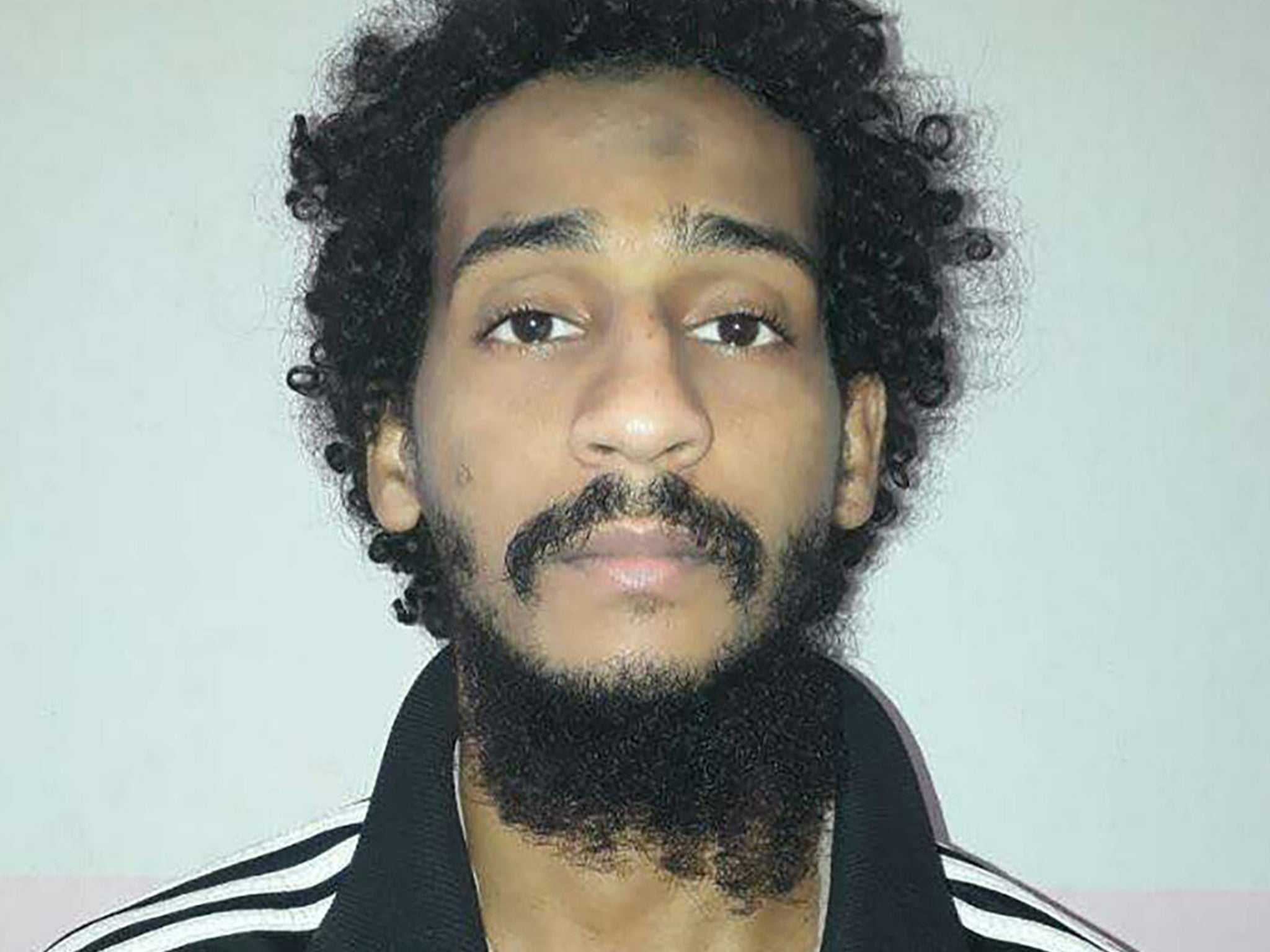

Ms Foley gave her testimony at the trial of El Shafee Elsheikh, a 33-year-old British Isis fighter charged with involvement in a vast hostage-taking operation, which ultimately led to the killing of Mr Foley and fellow journalist Steven Sotloff, and aid workers Kayla Mueller and Peter Kassig. The indictment also holds him responsible for the deaths of British aid workers David Haines and Alan Henning.

The second week of the trial began with the testimony from family members of the victims. Michael Foley, James Foley’s younger brother, described the last time he saw him in October 2012. He took him to the train station, where he began his journey to Syria.

“We expected him home by Christmas,” Michael told the court.

James was abducted in northern Syria on 22 November 2012, with fellow journalist John Cantlie. It wasn’t until January next year that the first communication from his captors arrived in the form of an email to Michael.

The email, shown to the court, read: “He is safe. He is our friend and we do not want to hurt him.” It added: “We want money fast.”

Subsequent communication with the hostage-takers would reveal that they were not serious about negotiating his release. On 27 December 2013, the captors demanded that the family pressure the US government to release “Muslim prisoners,” or alternatively deliver an impossible amount of €100,000,000.

Michael, and then his father, John, kept up their attempts to negotiate with the group, but the captors soon went quiet. There was a gap of nine months in contact when they received an email telling them James would be executed.

“When the US launched airstrikes against Isis in northern Iraq to prevent the massacre of thousands of Yazidi civilians who had escaped an attack, the hostage-takers emailed the Foleys to tell them that their son would be executed as a result.

“As for the scum of your country who are held prisoner by us, THEY DARED TO ENTER THE LION’S DEN AND WHERE [sic] EATEN.

“He will be executed as a DIRECT result of your transgressions toward us,” the email said.

Isis would soon release a choreographed video that showed James Foley’s decapitated body. They called it a “message to America”.

Mr Foley described the moment he found out about his brother’s killing while he was at work. He too received a call from a journalist asking for a reaction. “A reaction to what?” he asked.

He then went online and became aware of the video. He watched it “once or twice” immediately after its release, but never again.

Mr Foley and the jury were shown graphic images from that video by the prosecution in court on Monday.

“It is burned in my brain,” he told the court of the video.

Ms Foley also found out in a similar way. She was in Paris meeting released hostages who had been held with James when the family received the email telling them he would be killed. She rushed home. A few days later, she described the moment a sobbing journalist called her to ask if she had seen Twitter. That was when she discovered her son had been killed.

Earlier, she told the court that James – whom she referred to by his nickname, Jim – had put himself in danger “so that the world would know what was going on in Syria.”

“He was aware of the danger, but said he had promises to keep,” she said.

She described the desperate lengths the family went to in an effort to secure James’ release. The FBI had told them not to talk to the media, but she said she and her husband John became “frantic” and decided to hold a public press conference in which they appealed to his captors.

She then recounted the moment a former hostage of Isis who was held with James recounted to her a message from him that he had memorised before he left captivity. Daniel Rye Ottosen, a Danish photographer who was held by the group for 13 months, delivered the message to Ms Foley from her son in a phone call.

“It was such a gift,” Ms Foley said of the letter. “It was him talking to us, using words only Jim would have used.”

Prosecutors have alleged that Elsheikh was a member of the infamous “Beatles” Isis terror cell, nicknamed so by their captors because of their British accents. His defence has denied that he was a member of the cell, and instead claimed he was a “simple Isis soldier”.

The prosecution has presented interviews Elsheikh gave to the media following his capture in which he admits to overseeing and beating the victims named in the indictment.

One week in, the trial has already shone a light on the inner workings of the notoriously shadowy terror group, and revealed new horrors.

The prosecution has focused on the role of three British Isis “Beatles” in a widespread kidnap plot of at least 27 people in Syria between 2012 and 2015, most of them Westerners.

The other two Beatles have been named by the prosecution as Alexanda Kotey and Mohammed Emwazi, an executioner known by his nickname “Jihadi John”. Kotey pled guilty in September 2021 to his involvement in the murders of Foley, Sotloff, Meuller and Kassig, and is due to be sentenced next month. Emwazi was killed in a drone strike in 2015.