How Texas could have been French-speaking... had it not been for this maritime disaster

The state might have been very different had ‘La Belle’ not gone down in a storm in 1686

Timber by timber, stave by rotted stave, the wreck of a 17th-century French ship that had a profound if largely unknown impact on American history is being pieced back together, and is now set to reach its final resting place.

The wreck is that of the sailing vessel La Belle, and when it sank in Matagorda Bay, Texas, in 1686, France’s doomed New World settlement lost its lifeline. The mission, headed by reputed explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, ended in total disaster. To the bottom of the sea, along with La Belle, went the expedition’s entire stock of equipment for the settlement. The increasingly loathed La Salle was then murdered by his own men, and the nascent colony itself was wiped out.

The wreck of La Belle is to head to Austin’s Bullock Texas State History Museum later this month, to be exhibited permanently. La Salle’s body was never found and La Belle lay undiscovered for 300 years until in 1995, after decades of searching, it was finally discovered in waters so murky that divers had to rely on their sense of touch.

After 17 years of work to raise and restore the severely sea-damaged 60ft keel of La Belle, and the raising of a staggering 1.6 million artefacts from its hold, including 618,000 glass trading beads, 1,617 brass hawk bells (prized by Native Americans), and 1,603 brass “Jesuit rings”, the ship that could have made Texas French will again see the light of day.

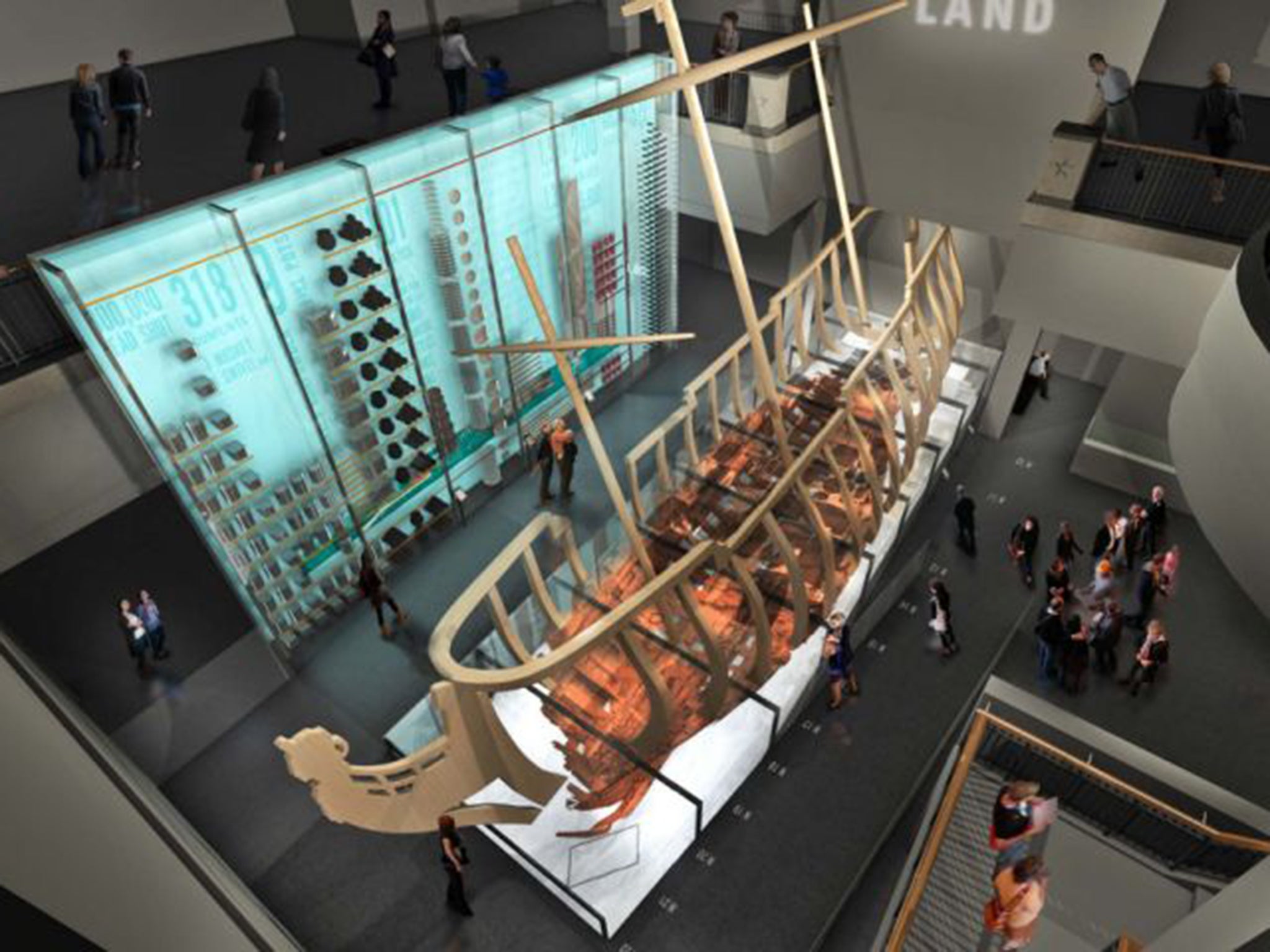

Visitors to Austin are currently able to watch curators reassemble and restore the 600 hull pieces in a temporary exhibition before its transfer to a specially built space where the rebuild will continue until 2016. Then both the hull and a full-size replica of La Belle will be viewable through a glass walkway.

As European superpowers battled hard to establish colonies in the New World, La Salle’s expedition forced Spain, then only nominally in control of what would become Texas, to react. They sent 11 expeditions to, as the military council in Madrid put it, “remove this thorn thrust into the heart of America”.

Madrid’s alarm was understandable. Interrogation of one Dionisio Thomas, an expedition survivor who had turned pirate and was later captured, revealed La Salle’s secret plans. It seemed the French wanted much more than a bridgehead in the Spanish-claimed territory. La Salle’s expedition also carried a hugely disproportionate amount of military weaponry such as iron petards, pot-au-fer grenades and 120,000 pieces of lead shot – an arsenal intended for a clandestine attempt to seize Spain’s silver mines in Mexico.

Jim Bruseth, the Austin museum’s guest curator for the La Belle exhibit, who has overseen its raising and restoration, says the mere presence of La Salle near Mexico “caused Spain to realise that if they were to hold on to today’s Texas they would need to send people up to occupy it”. That, in turn, led to the “wonderful Hispanic heritage that we have today. It’s a good example of how history often times turns on a small event”.

The expected showdown never took place. By the time the Spanish located the intended French settlement in 1689, all that remained were rotting timbers. Of the four ships La Salle had set out with, one was captured by pirates, another was back in France and two had sunk, among them La Belle which sank in a February storm in 1686. By January 1687, with no means of communicating with Europe and desperation setting in, La Salle, with a small group of men, headed out for French Canada, 1,500 miles away. He only made it 120 miles before being murdered in a mutiny over food. Almost all the colonists were subsequently wiped out by Karankawa indians.

Like the capsized Tudor warship Mary Rose, whose conservationists at the Portsmouth-based Mary Rose Trust collaborated with the Austin project, La Belle’s loss was disastrous short-term. But, as Dr Bruseth points out: “The tragedy and unique circumstances of the preservation of the ship have given us this time capsule to peer back into a period of North American settlement that we can see no place else.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks