Hope in the soap that has Haitians glued to the TV

Under the Sky has all the drama of EastEnders, and explains how to keep the rats at bay. Guy Adams reports from Port-au-Prince

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The grandfather has just caught his big toe in a rat trap, and to be blunt, he's spitting feathers. His wife won't let him into the kitchen until he calms down and stops swearing. His son-in-law, Akim, who originally set the trap and is therefore facing the brunt of the old man's rage, is duly trying to calm him down by explaining the importance of preventing vermin from spreading disease.

Fifteen minutes of knockabout banter later, this extended family has kissed, made up, and agreed that if only people weren't so inconsiderate as to leave enormous piles of litter lying around, then the refugee camp on the outskirts of Port-au-Prince – where they have been living since their home was destroyed just more than six months ago – would contain far fewer rats, and might therefore be an immeasurably better place.

It's just another crazy day on the set of Under the Sky, Haiti's newest comedy soap opera, which focuses on the daily lives of a family of ordinary, middle-class folk who, like 1.5 million of their countrymen, have lived in tents since January's earthquake, which killed 300,000 people and turned much of their capital to rubble.

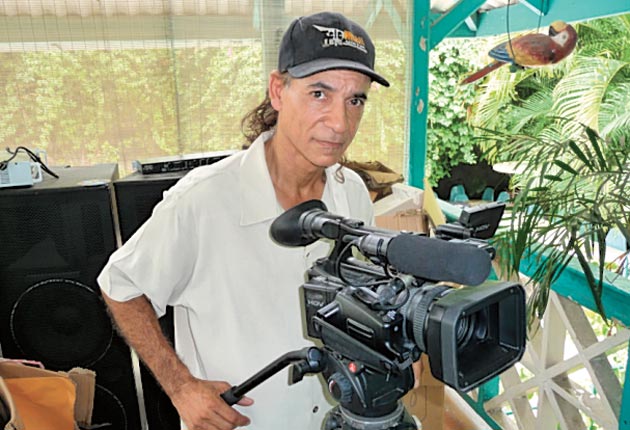

A new episode of the agreeably light-spirited show is written and filmed each week in a studio consisting of a couple of makeshift dwellings on the edge of a refugee camp in the city's Tabarre neighbourhood. This is where the director Jacques Roc – Haiti's best-known film-maker – likes to spend the night if filming runs over schedule, because, he says: "I need to know how people are really living."

Unlike the creators of, say, Albert Square, who are devoted to the pursuit of TV ratings, Mr Roc designs his show to educate, rather than simply to entertain. The United Nations provides $6,000 (£3,900) for each episode. Rather like The Archers, first conceived as a way of getting important information to British farmers in the years after the Second World War, it was created as a not-so-subtle medium for communicating officially sanctioned information to victims of the disaster.

In one recent plot twist, the family at the centre of the soap watched a dodgy neighbour hatch a scheme to buy and sell forged camp ID cards, which give their owners a right to free food, clothing and other handouts. He was eventually caught, and banned from receiving any charitable handouts whatsoever.

In another storyline, a distressed girl arrived at the family's shelter in tears, revealing she had been raped. After being comforted by her grandmother, played by the actress Elizabeth Alphonse, she identifies the culprit, who is arrested. The moral: women should report sexual abuse.

"Haitians are the sort of people who. if you go on the radio and tell them 'don't do this, don't do that', they just won't listen," says Mr Roc. "But if they watch a family going through certain situations, you can drop important information into the story without trying to feed it to them like they're in a school class. It can be very effective."

Other plots have demonstrated how refugees can assess if it is safe to return to their damaged homes, and have talked about refugee-camp etiquette. If someone lives in a dwelling that does not have a door, the family decide they should nonetheless announce their impending arrival, by politely shouting: "Knock, knock!"

The UN hopes that, in addition to communicating important, and possibly life-saving, information, Under the Sky will help Haitians to combat one of the most under-reported and dangerous problems of everyday life in a refugee camp: boredom. With almost no employment, most inhabitants of the tent cities have little to do except sit around in the blazing heat. And aid workers are often prone to observing that the Devil makes work for idle hands to do.

Those refugees who have some money to their name have rigged-up small television sets in their dwellings. But now the World Cup has finished, there is little on the airwaves to interest them except re-runs of badly dubbed American soap operas.

Under the Sky airs on national television most weekday evenings, although broadcasters are frequently forced to air old episodes of the show, which will eventually run to 16 instalments, since heavy rainstorms have interfered with Mr Roc and his 24-strong crew's filming schedule. "When it rains, the camp just turns to mud. It is impossible to even walk outside, let alone make a TV show," he says.

For Haitians who cannot afford their own television, the soap opera is also being shown after dark on one of a dozen big mobile projector screens, which the UN transports from camp to camp, depending on the day of the week. Screenings can draw crowds of 10,000, Mr Roc says.

The show's stars – who include two of Haiti's best-known male actors, Lionel Benjamin and Junior Metellus – portray characters who come from a solidly middle-class background. They dress relatively smartly, and the dwellings in which they have been forced to take up residence contain books, table cloths, and other bourgeois accoutrements.

"We thought it was important for them to be that way," says Mr Roc, an excitable character who is himself from Haiti's upwardly mobile class: after studying in New York in the 1980s, he built a successful career in the US, where he made more than 240 television adverts.

"There is a perception that only the poor are in the camps," he adds. "That just isn't true. The earthquake was a very democratic disaster: it cuts across all classes, and a lot of middle-class people lost homes as well. In the camps you see people who get up in the morning, put on a suit and drive a car to work. If we had picked a poor family it would have been totally condescending. It would have suggested that the only people living in tents in this country are poor people; people without an education. To me, nothing would have been more inappropriate."

Mr Roc takes instruction from David Wimshurst, the UN's communications chief in Haiti, as to the serious themes his show must cover. In one episode, the family nod sagely when a newsreader on the radio declares that their government and UN are collaborating to "rebuild" the country. Future instalments will look at issues including the prevention of Aids, how to avoid mosquito bites, domestic violence and sanitation.

But Mr Roc is adamant that there will always be a place for pratfalls and slapstick and old men getting their feet caught in rat traps. "Haitian people, they love comedy," he says. "Even with conditions as they are, people still need to have a laugh, so I try to help them with that. You can say that I am a propagandist, but I try to be one in the nicest possible way."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments