‘Frozen in time’: Eerie footage inside 170-year-old shipwreck from lost Arctic expedition

HMS Terror exploration reveals potential ‘treasure trove’ of preserved documents and photographs, say scientists

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Archaeologists have captured unprecedented footage of an Arctic shipwreck “frozen in time” for more than a century and a half.

Video from inside HMS Terror reveals china plates and bottles still stacked on shelves, eerily well-preserved officers’ cabins and weapons still in their racks.

Tantalisingly, scientists believe that paper and photographic records of the ship’s last years may still be intact inside cupboards and desks aboard the wreck.

“Artefacts have been essentially frozen in time for approximately 170 years” thanks to frigid temperatures and sediment build-up, said Parks Canada in a statement.

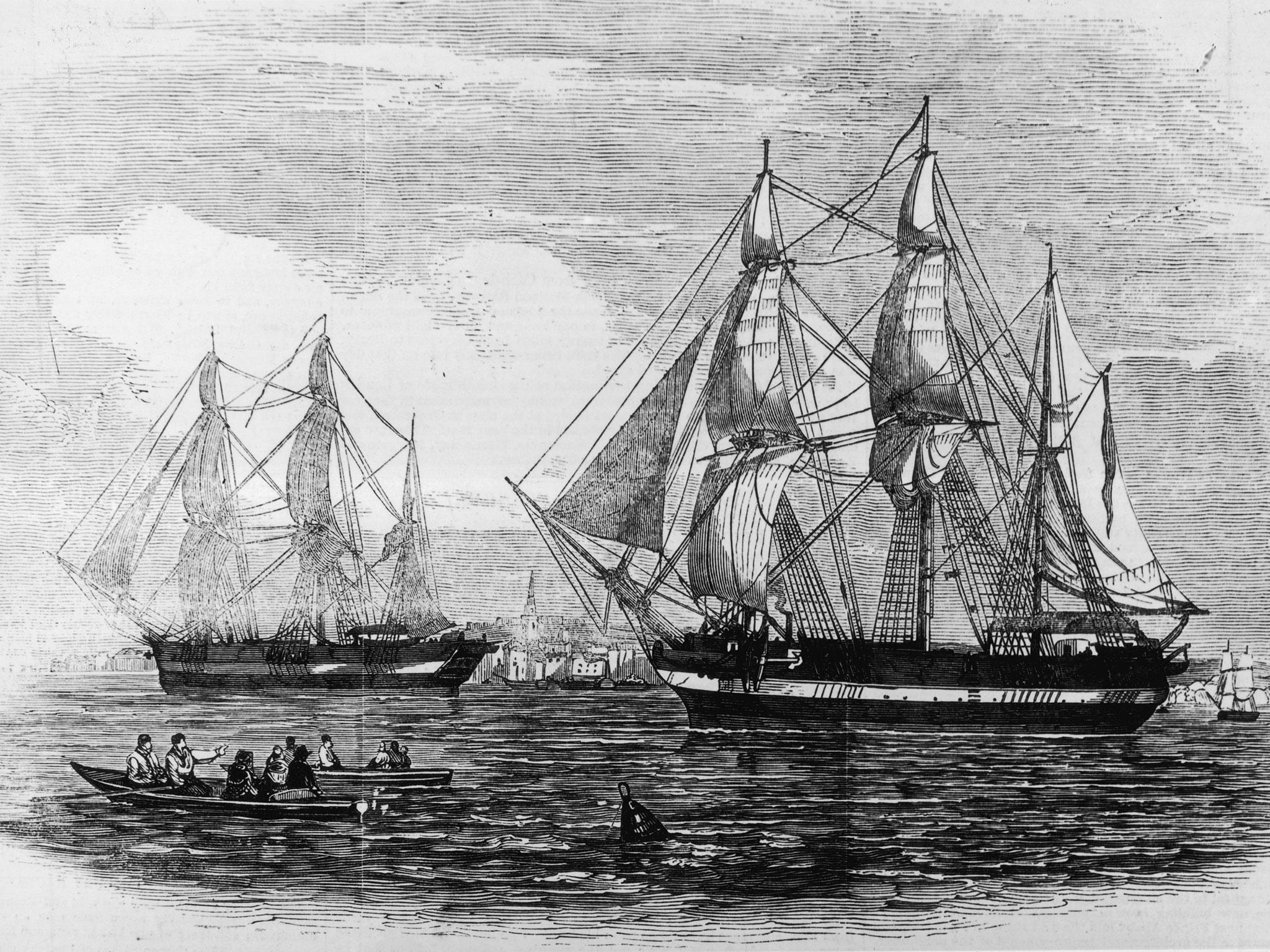

Terror was one of two ships in a doomed expedition to complete the navigation of the Northwest Passage, which left England in 1845 and was led by Sir John Franklin.

She and her partner vessel HMS Erebus were former warships, made state-of-the-art with upgrades including heating systems, iron-reinforced hulls to resist the pressure of Arctic ice and steam engines taken from railway locomotives to drive their screw propellers.

They set sail with three years’ worth of supplies, 12 days’ coal fuel and orders to finally chart a shortcut sea route from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Their 129 crew were last seen by Europeans in late July 1845, newspaper records suggest.

But the following year, both ships became trapped by pack ice off King William Island in remote northern Canada, where the expedition spent two winters.

Franklin died a year before his remaining crew abandoned the ships and attempted to walk back to civilisation, in 1848. They never reached it, and evidence suggests that in their desperation some resorted to cannibalism.

Erebus’ wreck was discovered in 2014, and Terror’s two years later. Archaeologists from Parks Canada have worked with Inuit in the region to explore and preserve the sites.

This new footage was captured using a remotely operated vehicle, which divers dropped through a hatch on Terror’s upper deck. In all the drone explored 20 compartments on a single deck over seven days in August.

Its operator, Ryan Harris, said: “The impression we witnessed when exploring ... is of a ship only recently deserted by its crew, seemingly forgotten by the passage of time.”

The best-preserved area was the cabin of her captain, Francis Crozier. Marc-Andre Bernier, underwater archaeology manager of Parks Canada, said in a statement: “The condition in which we found Crozier’s cabin greatly surpasses our expectations.

“Not only are the furniture and cabinets in place, drawers are closed and many are buried in silt, encapsulating objects and documents in the best possible conditions for their survival.

“Each drawer and other enclosed space will be a treasure trove of unprecedented information on the fate of the Franklin expedition.”

The only area the team was unable to access was Crozier's sleeping quarters, behind the single closed door on the deck they explored.

Any artefacts brought to the surface in the future will be jointly owned by the Canadian government and the Inuit. Parks Canada hopes to reconstruct the experiences of individual crew members using the data gathered during the August dives.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments