Why I went to prison to visit the school shooter who left me paralysed

Michael Carneal will become one of the first school shooters to appear before a parole board later this month. Missy Jenkins Smith, who’s been paralysed from the chest down since Carneal opened fire on a prayer circle of Kentucky students in 1997, tells Sheila Flynn how she feels about the fact her attacker - who killed three - might go free

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Missy Jenkins Smith was almost nine months pregnant, paralyzed from the chest down, when she visited the man who shot her in prison.

Michael Carneal had been her 14-year-old high school bandmate in West Paducah, Kentucky. Then he walked into Heath High School with stolen guns on a Monday after Thanksgiving break in 1997, opening fire on a morning prayer circle of students.

Missy was hit and permanently incapacitated. She initially thought it was a joke when she saw another girl, 14-year-old Nicole Hadley, fatally shot in the head. Missy’s twin, Mandy, was grazed and crawled over to protect her sister as students tried to make sense of who was shooting in the hallway.

Jessica James, 17, and Kayce Steger, 15, were also fatally wounded before Carneal ended his attack, a massacre that shocked the small Kentucky community and the country less than a year and a half before Columbine anchored school shootings as a national horror.

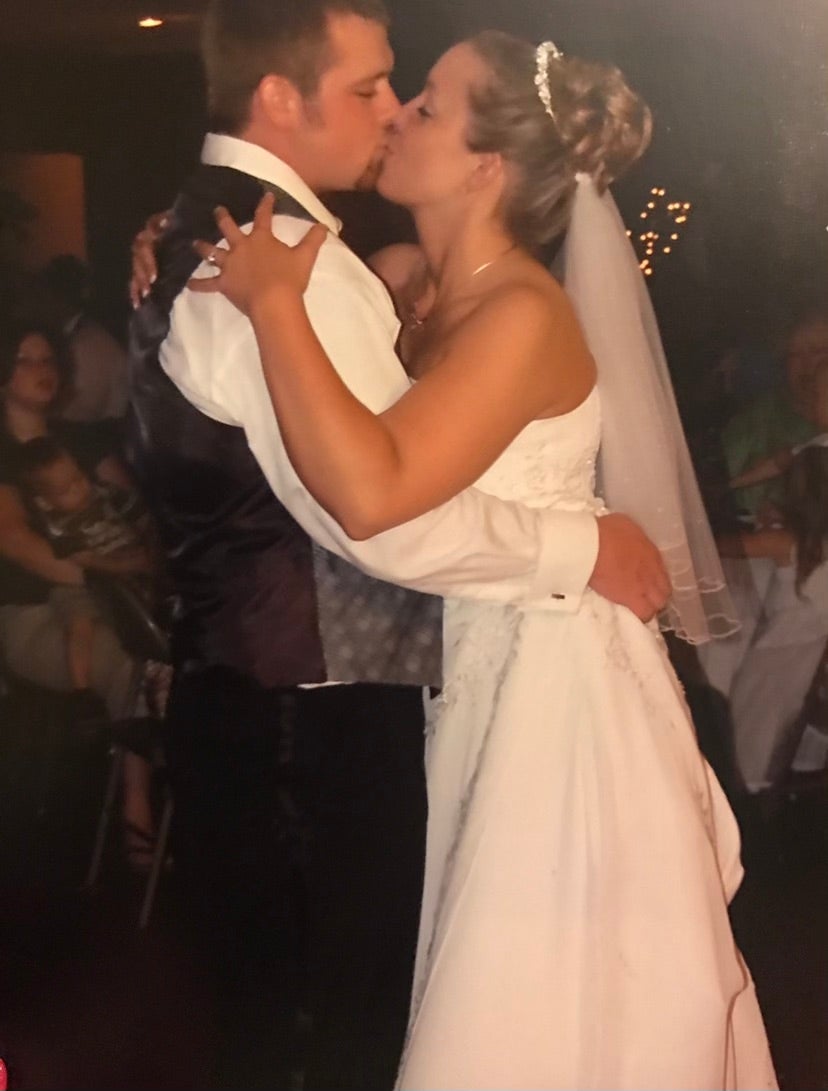

Missy went to see Carneal – a boy she’d never thought capable of such violence – ten years after the shooting, while she was expecting her first son with her husband, Josh. Carneal had been sentenced to life in prison with a possibility of parole after his defence focused on bullying and mental illness.

Despite her significant injuries, Missy finished high school, went to college, got married and was giving speeches about her experience.

“I knew I wasn’t going to get a reason why he did it, a specific reason,” Missy tells The Independent of her visit to Carneal. “I wasn’t there seeking an apology. But I wanted ... to see if I could get whether he would have chosen, if he could choose to go back, [to make] the same decision.

“And I thought that would be something powerful that I could deliver to kids when I spoke,” she says, adding: “He told me that he did regret what he did. He wished he hadn’t. And then, at the end of the conversation, he did tell me he was sorry.

“Well, after that, he started to work on an appeal ... he had plead guilty, but mentally ill, but was wanting to change it to not guilty by reason of insanity. He did this plenty of times. And he was denied every single time.”

Coping with Carneal’s rare hope of parole: ‘Could happen again?’

Now, however – right after her son’s 15th birthday – Carneal is coming up for parole, one of the few school shooters to have reached this point.

Missy has written a 27-page letter to the parole board detailing how the shooting changed her life – and what her fears may be regarding his release.

During his appeals, she says, he was “really leaning on mental illness.” She’s very conscious that Carneal has spent the majority of his life in jail – just like she’s now spent the majority of her life in a wheelchair.

“He’s had someone responsible for him since he was 14 years old,” she says. “Anybody who’s 14 would start the responsibility of taking care of themselves, normally, at the age of 18. That was just four more years after his age at the time to start working on taking care of [yourself], becoming an adult.”

Now, though, it’s been a quarter-century – and the world, she points out, has vastly changed. Technology is different. The world is completely different. He’ll have to find a job as a convicted murderer and an infamous school shooter.

“How can there not be stress from that?” she says. “And that stress not trigger him, maybe?”

She also wasn’t thrilled after she discovered Carneal had been featured on a murder memorabilia site; offenders can’t profit while incarcerated, but there were items of his on there and a Q&A interview.

“Almost like they were interviewing him like for a dating service – like, what’s your favourite colour, what’s your favourite flavor ice cream, what do you look for in a girl, all those kinds of things,” she says.k “And what bothered me was like, okay, he’s considering himself as a serial killer. He’s okay with this.”

She realized this about 10 years ago, she says.

“He was about 29 or 30. I mean, that’s plenty old enough to know better,” she says. “He told me he was sorry, but ... to me, that doesn’t sound like there’s a lot of sorry in it.

“Could this possibly be something that happens again?”

The day Missy’s bandmate became a school shooter

Before the shooting, she says, she’d never had any concerns about Carneal and considered him a friend.

“I really liked him,” she says. “He was a class clown. He always made me laugh. He always made a boring day, something like, what’s Michael going to do? You know? And it wasn’t every anything scary, it was just something that was silly or whatever.

“But my school had a severe problem with bullying. So I mean, there were times where he might do something - and I always thought he was funny - but there were some people that, you know, would treat him like he was, you know, annoying or whatever it may be ... so he dealt with that, but that doesn’t mean I give him an excuse whatsoever.”

She says she remembers being slightly jealous, in fact, at how Carneal seemed able to brush off the bullying - until the day he unleashed a bloodbath in the high school hallway before he stopped shooting.

He was the last person she thought would be responsible for such horror on a day that started so normally. Missy was rushing to leave the house that morning so her older sister wouldn’t leave for school without her; to this day, she regrets not telling her parents she loved them as she said goodbye.

She’d face her own mortality minutes later.

After getting to school, she and Mandy were in the hallway when the announcement was made for a daily prayer circle, as students gathered before class to reflect and pray about anything that might be on their minds.

That’s when she heard what sounded like firecrackers. She saw Nicole get shot and, she thinks, went into shock - right around the time a bullet hit her, too.

“I don't honestly honestly think that he was after the prayer circle,” Missy tells The Independent. “But he was after a big group of people.”

It turned out that Carneal had stolen guns from a neighbour, disguising them and ammunition as a science project as he got a lift to school with his sister on that fateful morning. Around 7.45am, he put in ear plugs, pulled out a Ruger and began firing, killing the three girls and wounding five other people before the principal approached him and he put down the gun.

The story made national headlines for weeks. Then, in 1999, the breadth and toll of Columbine - combined with the footage, increasing 24 news and ghastly footage of the Colorado massacre - shone an even larger spotlight on the violence and tragedy of school shootings.

Missy says she has personal concerns about Carneal’s parole; during her senior year, she says, Carneal was writing her letters and calling her house, all while still behind bars.

“Who’s to say that he wouldn’t want to come check me out today?” she says. “And I really don’t want to talk to him.”

The 25-year toll of partial paralysis

As Carneal looks forward to the possibility of walking free, Missy will never walk again. Even composing the letter to the parole board has been a massive effort.

“I was trying to handwrite everything, and I was wanting to be very personal,” she tells The Independent. “But then on the other hand, I have a lot of injuries now because of the use of my arms constantly for the past 25 years.”

Carpal tunnel, an injured rotator cuff, even a dying bone in her wrist - her arms have borne the brunt of her paralysation, and it’s starting to take its toll.

“It’s made my writing sloppy,” she says - yet, after a little help, she sent the parole board letter off last week.

Trouble writing, however, is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to how Carneal forever changed her young life.

“One of the things that’s been the hardest the entire time, with this whole process, is that I’ve lost the use of ... my bladder and bowel function,” she says, describing the shock of realising, as she was in the hospital after the shooting, she would have to catheter herself for the rest of her life.

The first day she returned to school, she had an accident and - completely understandably - collapsed into tears.

“Over the years, it’s been hard dating or whatever; you were scared to death to tell a guy that, hey, this is what I have to do,” she says. “But then as I got older and dated, I realised that people don’t care about that as much as I did ... I also kind of got tired of living my life around my bathroom situation.”

She has certainly gone on to have a full life; in addition to speaking and writing books, she and her husband have two sons, ages 15 and 12.

But with the rash of school shootings - and both of them middle- and high-school age - she has a very measured perspective as she sends her boys to class, though she admits a 2018 school shooting nearby particulary unsettled her.

“I’ve learned that you can’t live in fear,” she tells The Independent. “You’ve got to live, but at the same time, you can’t live like everything’s okay and that you’re going to be fine.

“And I’m not saying that you’re constantly looking for, you know, warning signs. But when there is something out there that is deliberately in your face, something you don’t take lightly, tell somebody,” she says.

Carneal, for example, had shown a gun at school before the massacre but was never taken seriously.

“If you don't say something, and something happens, then you would have wished you did,” she says.

She says that she forgives Carneal, with caveats.

“The reason why I forgave him was for me,” she tells The Independent. “I think a lot of people think that when they forgive somebody, that it's going to let that person off.

“But it was so I could move on with my life. so I didn't have to have anger in my life, so that I didn't have to let December 1 control me for the rest of my life. And so I wanted to move on.

“And so it didn't exonerate him for the consequences ... for killing three girls and injuring five people and changing so many lives.

“And that was the other thing, you know, if you were to be given parole at 39, he could potentially still have a life,” she says. “He could still get married, he could still have children. He still has 40 years, potentially, of, you know, living this life. And there were three girls that only got at least one decade to live their lives.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments