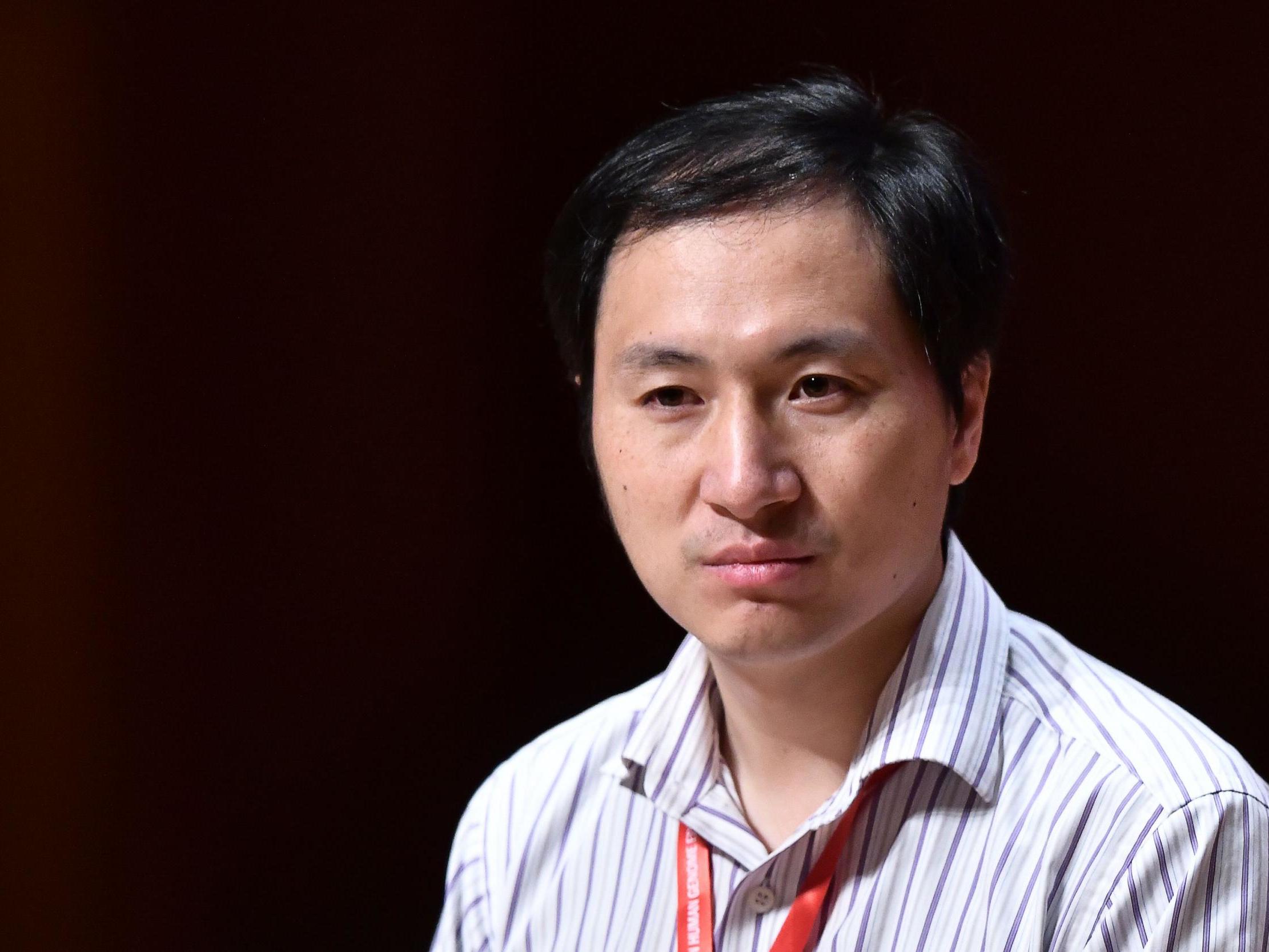

Cowboy scientist who created world’s first gene-edited baby 'had help from top US professor'

Correspondence obtained provides revealing window into the informal way researchers navigate a fast-moving, ethically controversial field

“Success!” read the subject line of the email.

The text, in imperfect English, began: “Good News! The women is pregnant, the genome editing success!”

The sender was He Jiankui, an ambitious, young Chinese scientist. The recipient was his former academic adviser, Stephen Quake, a star Stanford bioengineer and inventor.

“Wow, that’s quite an achievement!” Professor Quake wrote back. “Hopefully she will carry to term...”

Months later, the world learned the outcome of that pregnancy: twins born from genetically engineered embryos, the first gene-altered babies.

Reaction was fierce. Many scientists and ethicists condemned the experiment as unethical and unsafe, fearing that it could inspire rogue or frivolous attempts to create permanent genetic changes using unproved and unregulated methods.

A Chinese government investigation concluded in January that Prof He had “seriously violated ethics, scientific research integrity and relevant state regulations”.

Questions about other American scientists’ knowledge of Prof He’s plans and their failure to sound a loud alarm have been an issue since Prof He revealed his work in November.

But now, Prof Quake is facing a Stanford investigation into his interaction with Prof He.

That inquiry began after the president of Prof He’s Chinese university wrote to Stanford’s president alleging that Prof Quake had helped Prof He.

“Prof Stephen Quake provided instructions to the preparation and implementation of the experiment, the publication of papers, the promotion and news release, and the strategies to react after the news release,” he alleged in letters obtained by The New York Times.

Prof Quake’s actions, he asserted, “violated the internationally recognised academic ethics and codes of conduct, and must be condemned”.

Prof Quake denied the allegations in a lengthy interview, saying his interaction with Prof He, who was a postdoctoral student in his lab eight years ago, had been misinterpreted.

“I had nothing to do with this and I wasn’t involved,” Prof Quake said. “I hold myself to high ethical standards.”

Prof Quake showed The New York Times what he said were the last few years of his email communication with Prof He.

The correspondence provides a revealing window into the informal way researchers navigate a fast-moving, ethically controversial field.

The emails show that Prof He, 35, informed Prof Quake, 49, of milestones, including that the woman became pregnant and gave birth.

They show that Prof Quake advised Prof He to obtain ethical approval from Chinese institutions and submit the results for vetting by peer-reviewed journals, and that he agreed to Prof He’s requests to discuss issues like when to present his research publicly.

None of the notes suggest Prof Quake was involved in the work himself. They do contain expressions of polite encouragement like “good luck!”

Though Prof Quake said he urged Prof He not to pursue the project during an August 2016 meeting, the emails, mostly sent in 2017 and 2018, don’t tell him to stop.

As global institutions like the World Health Organisation work to create a system to keep cowboy scientists from charging into the Wild West of embryo editing, Prof Quake’s interactions with Prof He reflect issues that leading scientific institutions are now grappling with.

When and where should scientists report controversial research ideas that colleagues share with them in confidence? Have scientists acted inappropriately if they provide conventional research advice to someone conducting an unorthodox experiment?

“A lot of people wish that those who knew or suspected would have made more noise,” said R. Alta Charo, a bioethicist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who co-led a 2017 national committee on human embryo editing.

But she said scientists were not necessarily complicit if instead of trying to stop rogue experimenters, they advised them to follow ethical and research standards in hopes that institutions would intervene.

Rice University has been investigating Michael Deem, Prof He’s PhD adviser, because of allegations that he was actively involved in the project; he had said publicly that he had been present during parts of it.

Prof Deem’s lawyers issued a statement strongly denying the allegations.

The correspondence Prof Quake shared provides new details about Prof He’s project, also called germline editing, including indications that the twin girls were quite premature and remained hospitalised for several weeks. They were born in October, contrary to previous reports.

Prof Quake is an entrepreneur whose inventions include blood tests to detect Down syndrome in pregnancy and to avoid organ transplant rejection.

He is co-president of an institute funded by Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and his wife, Dr Priscilla Chan.

He does not do gene editing and said he was surprised when Prof He told him during a 2016 visit to Stanford that he wanted to be the first to create gene-edited babies.

“I said, ‘That’s a terrible idea. Why would you want to do that?’” Prof Quake recalled. “He kind of pushed back and it was clear that he wasn’t listening to me.”

Prof Quake changed tack. “I said, ‘All right, if you’re not going to be convinced that I think this is a bad idea and you want to go down this path, then you need to do it properly and with proper respect for the people who are involved, and the field.’”

That meant obtaining ethical approval from the equivalent of US institutional review boards (known as IRBs), Quake advised, as well as getting informed consent from the couples participating and only editing genes to address a serious medical need.

“I didn’t think it was something he would seriously do,” said Prof Quake, adding that he assumed if Prof He sought ethical approval and was rebuffed, “presumably he’d stop”.

Soon afterwards, Prof He emailed: “I will take your suggestion that we will get a local ethic approve before we move on to the first genetic edited human baby. Please keep it in confidential.”

In June 2017, Prof He, nicknamed JK, emailed a document saying a hospital ethics committee had approved his proposal, in which he boasted that his plan could be compared to Nobel-winning research.

“It was good to see that he had engaged with his IRB-equivalent there and had approval to do his research, and I’m thinking it’s their responsibility to manage this,” Prof Quake said in the interview.

“If in my interactions with JK I had any hint of misconduct, I would have handled it completely differently. And I think I would have been very aggressive about telling people about that.”

In Prof He’s 2017 correspondence, he said he would be editing a gene called CCR5, altering a mutation that allows people to become infected with HIV.

Many scientists have since argued it was medically unnecessary because babies of HIV-positive parents can be protected other ways. Prof Quake said he believed there was not scientific consensus about that.

In early April 2018, Prof He’s “Success!” email said “the embryo with CCR5 gene edited was transplanted to the women 10 days ago, and today the pregnancy is confirmed!”

Quake did not reply immediately. Instead, he forwarded the email to someone he described as a senior gene-editing expert “who I felt could give me advice”. He redacted the name of the expert.

“FYI this is probably the first human germ line editing,” Quake wrote. “I strongly urged him to get IRB approval, and it is my understanding that he did. His goal is to help HIV positive parents conceive. It’s a bit early for him to celebrate but if she carries to term it’s going to be big news I suspect.”

The expert replied: “I was only telling someone last week that my assumption was that this had already happened. It will definitely be news ...”

Prof Quake considered that response “very blasé,” he said. “He’s not surprised at all. And he’s not saying, ‘Oh my god, you got to notify the mythical science police.’”

Six months later, in mid-October, Prof He emailed again: “Great news! the baby is born (please keep it in confidential).”

He asked to meet on a planned visit to San Francisco, saying, “I want get help from you on how to announce the result, PR and ethics”.

Prof Quake replied, “Let’s definitely meet up.”

In that meeting, Quake recalled, Prof He walked him through what he had done.

“And I pressed him on the ethical approval, and I said this is going to get an enormous amount of attention, it’s going to be very closely scrutinised. Are you sure you’ve done everything correctly?”

He’s response unsettled him, he said. “The little corner-cutting thing came up again: ‘Well, there were actually two hospitals involved and you know, we had approval from one and we did work at both hospitals.’

“And I said, ‘Well you better make sure you have that straightened out’.”

Back in China, Prof He wrote: “Good news, the hospital which conducted the clinical trial approved the ethic letter,” adding, “They signed to acknowledge the ethic letters from another hospital.”

Prof Quake replied, “Great news, thanks for the update.”

About a week later, Prof He’s publicist, Ryan Ferrell, contacted Quake, worried that Prof He presenting the project publicly so soon could cause “severe and permanent harms to his reputation and the field”.

And, “the twins are still in the hospital, so no positive imagery”.

Prof Quake, in Hong Kong for other commitments at the same time as a genome-editing conference, met He and Mr Ferrell, telling them, “you’re going to be held to a very high standard,” he said. “‘People’s first response is going to be you’re faking it.’”

He advised Prof He to submit the research to a peer-reviewed journal, and He did so.

Then, because journal review takes time, Prof Quake said he advised He not to go public in Hong Kong, but to speak privately with key experts there so they can “get socialised to what’s coming and will be more likely to comment favourably on your work”.

But Prof He was not persuaded. “I do not want to wait for 6 months or longer to announce the results, otherwise, people will say ‘a Chinese scientist secretly hide the baby for 6 months’.”

Prof Quake pushed back: “It is prudent to let the peer review process follow its course.”

But Prof He went forward with his Hong Kong talk.

Two days before it, after news of the twins broke, Quake emailed, “Good luck with your upcoming presentation!” But he added, “please remove my name” from the slide acknowledging people who had helped.

“He was spinning up this huge press thing around it,” Prof Quake explained in the interview. “It was going to go well or poorly, I didn’t really know. But it wasn’t something I was involved in and I didn’t want my name on it.”

The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks