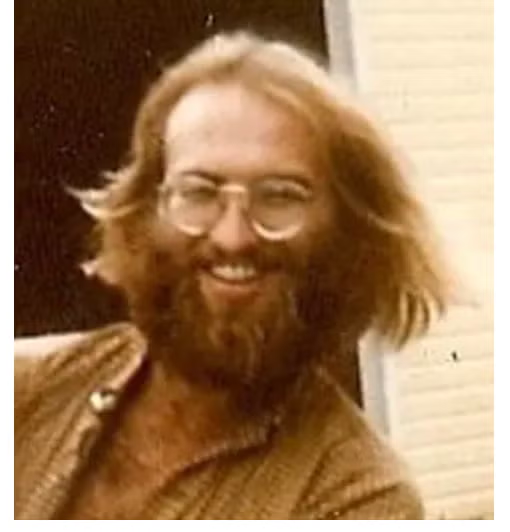

Human skull found in Alaska two decades ago belongs to man mauled by bear in 1976

Nearly 50 years after Gary Sotherden vanished while hiking in the remote Alaska interior, the mystery of his death has been solved through DNA

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A human skull found in a remote Alaskan river valley in 1997 has been genetically linked to a New York man who was likely killed by a bear 20 years earlier, Alaska State Troopers say.

The remains were confirmed to be Gary Frank Sotherden, 25, who had gone missing while exploring the Alaskan interior in the late 1970s, spokesperson Tim DeSpain told the Associated Press.

“Based on the shape, size and locations of tooth penetrations to the skull, it appears the person was a victim of bear predation,” Mr DeSpain told the AP.

Sotherden’s fate had remained a mystery for nearly 50 years until last month, when Alaska State Troopers using genetic testing and genealogy mapping were able to confirm the identity of the remains.

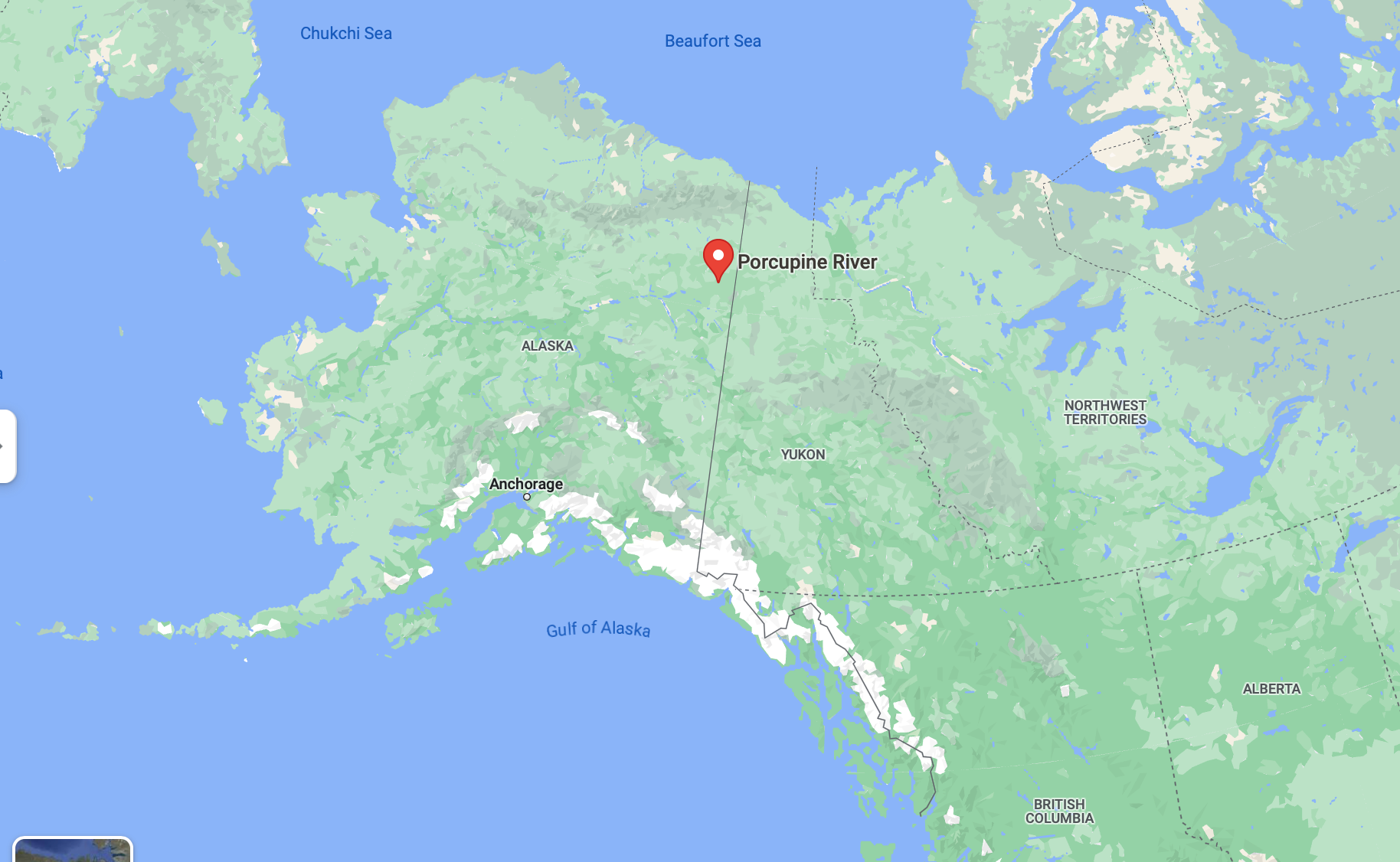

Sotherden’s brother Stephen Sotherden toldthe New York Times that after his “free spirited” brother went missing in 1976, their parents had hired a mountain guide who had canoed down the Porcupine River and located Gary’s broken glasses and identification.

The family initially thought that Gary Sotherden, from Clay, in upstate New York, may have died of hypothermia due to a spell of bad weather passed through the area.

Then in 1997, a hunter contacted authorities to say he had found a skull near to the Porcupine River, about 8 miles (13kms) from the Canadian border.

Troopers searched the area but found no further remains. The skull was listed as unidentified, and the medical examiner’s office said the likely cause of death was put down to bear mauling.

Mr DeSpain said in a statement that recent advances in genetic genealogy sciences led a cold case unit and the medical examiner’s office to send samples from the skull to public DNA databases.

A tentative match was found, and last year troopers asked a second cousin of Gary Sotherden’s to submit a DNA sample.

Stephen Sotherden told the New York Times he received a call in December to say that genealogists had linked the skull to a second cousin, and ask that he provide a DNA sample.

He had recently submitted his DNA to the 23andMe ancestry site, and troopers were able to use the same sample to confirm the link to his brother.

After Gary’s disappearance, Stephen Sotherden told the Times the family had placed a tombstone in his brother’s memory in the family cemetery plot with the words: “Lost in Alaska in the 1970s”.

After finally getting confirmation of his brother’s fate, they would hold a memorial later this year for him, he said.

“We’ve been working on it for 45 years, and it’s nice that things came to a conclusion,” he told the Times.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments