A time bomb ‘supercharged’ by the pandemic: How white nationalists are using gaming to recruit for terror

Experts are warning that far-right agitators are using online gaming platforms to spread hate and recruit a new generation of converts. Supercharged by the rise of gaming and social isolation during the pandemic, extremism academics say more needs to be done to police these platforms for grooming hate. Io Dodds reports

The player's profile picture raised no red flags: just the smiling Lego like-face of a typical Roblox avatar, little different from the estimated 220 million people who log in at least once a month to the wildly popular children's video gaming platform.

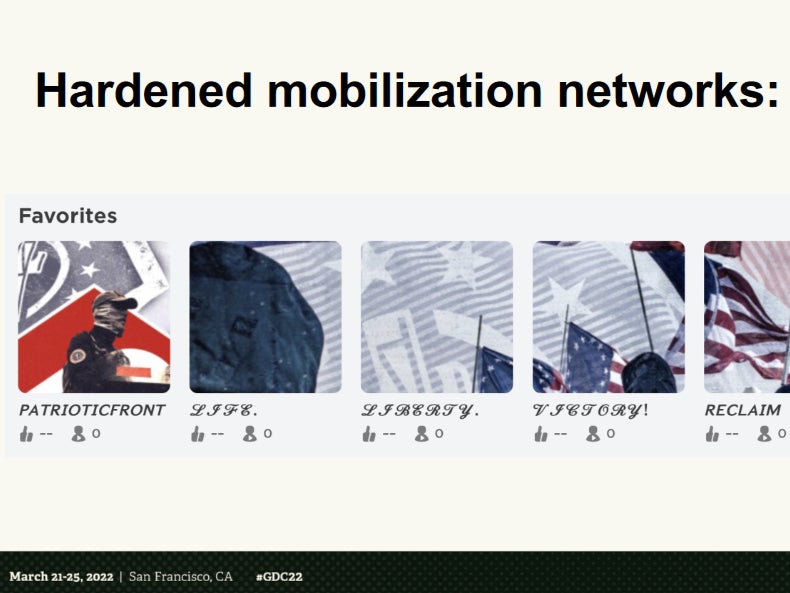

On closer inspection, however, the player's "favourites" list had been arranged into an impromptu mosaic with the words: "Patriotic Front. Life, liberty, victory! Reclaim America!" The Patriot Front is an American group of fascist street fighters, who use "reclaim America" as their slogan.

The player was also part of an in-game group called Justice 4 Floyd, whose logo appeared to be based on the black shield of Nazi German SS combat divisions in the Second World War. That group was linked by "alliances" to other Roblox groups with names such as the British Nationalist Vanguard, the Condor Division (similar to the Nazis' Condor Legion), and the New Hampshire 2nd Infantry Platoon, whose description bore references to known neo-Nazi groups.

This is just one of the suspicious networks uncovered in popular video games and gaming-related social networks by Alex Newhouse, a researcher at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies in Monterey, California. In a talk last week at the Game Developers Conference in San Francisco, he and gaming psychologist Rachel Kowert laid out evidence of how the gaming boom of the pandemic era has given far-right extremists, who have long been active in gaming communities, new opportunities to recruit and organise.

Worse, Mr Newhouse argues that major gaming companies, in their quest to attract and retain users, are expanding the features that extremists can weaponise while failing to increase their safety efforts at the same pace – creating an online time bomb that could lead to offline violence.

"As games are becoming more and more like social media platforms themselves, with all the features that you would expect from a Facebook or a Twitter, like groups and channels and friend lists and all that, they become attractive to extremists who have been deplatformed by Facebook and Twitter," he tells The Independent.

"We know that extremists are intentionally structuring these networks to mobilise people to violence. They say as much, and we've interviewed former extremists who talk about this... there are individuals who are actively on the lookout or people they think can be spun out into a mass shooter or a terrorist."

Extremists flock to Steam, Discord and Roblox

Gaming is no stranger to the far right. The hobby's large quotient of disaffected and socially isolated young men has long proved attractive to extremist groups, who have a historical pattern of exploiting unexpected online services to spread their message.

Mr Newhouse was a reporter at GameSpot in 2014 when resentment over the increasing prominence of feminism and minority advocacy in gaming communities exploded into a reactionary movement known as Gamergate. The controversy spawned intense harassment campaigns against female and non-white game developers and galvanised the careers of activists and influencers who later became key figures in the "alt right".

Gamergate also gave rise to 8chan, an online message board, which has since became a central organising space for terrorists across the world. This was where the Christchurch mosque gunman in 2019 posted his manifesto, peppered with references to gaming culture, and where "Q" – the mysterious messiah of the QAnon movement – posted almost all of their conspiratorial prophecies.

"In a cruel twist of fate, games critics and games media are still today, in some ways, much better equipped to handle the current landscape of extremism and disinformation than the people who were covering terrorists in the 2000s, in early 2010s," says Newhouse, who later worked on data privacy at Sony Playstation and is now deputy director of Middlebury's Center on Terrorism, Extremism and Counterterrorism.

Last year, Mr Newhouse noticed an "increasing amount of chatter" in extremist networks that suggested their members were moving in large numbers to services such as Discord, a group chat app popular with gamers, and Steam, an all-purpose online gaming platform that combines store front, social network and games library.

The timing coincided with a series of crackdowns by major social networks in the wake of violent attacks linked to extremist communities such as QAnon and Boogaloo, culminating in the storming of the US Capitol in January 2021. Mr Newhouse suspects that was one motive for the migration, though he cannot be sure.

Discord, he told the GDC audience, "has become probably the main place for the initiation of someone from the early stages of radicalisation into increasingly robust [far-right] socialisation and identity". He says extremist communities often use a Discord "server" – effectively a linked group of chatrooms, which can be public or private – as a hub for activity in various video games.

Why Discord? Partly because it's already popular, especially with the white men and boys aged 15 to 22 who far right groups tend to target. But Mr Newhouse also says: "Discord has shown that it's relatively unwilling to take pretty significant action against these groups.

“They're able to post under the radar well enough that they don't get as much attention as the big Telegram or Facebook networks... it's probably the most popular, least enforced platform."

'Groomed via online gaming'

In 2017, Discord's staff learned that their app had been one of the major organising places for the Unite the Right white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, at which an avowed neo-Nazi killed one person and injured 35 in a vehicle ramming attack.

At the time, Discord’s "trust and safety" team consisted of one person. The event sparked change inside the company, and by last May the safety team had swelled to about 60.

Yet the problem persists. An investigation in August by the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD), a British think tank, found 24 extreme right servers on Discord; 100 such channels on the livestreaming service DLive; 91 channels on Twitch, a better-known livestreaming service owned by Amazon; and 45 public groups on Steam.

Steam appeared to host the most entrenched and long-lasting networks, acting as a community hub, while Discord servers had short life-cycles due to the company's crackdowns and were used to provide "safe spaces" for young people to explore extremist ideas and to coordinate harassment campaigns against minority groups.

Meanwhile, journalists have found numerous examples of far right groups building propaganda content in video games, such as interactive Nazi concentration camps in Minecraft and Roblox.

The ISD's report also found evidence that several extreme right Discord servers hosted many under-17s, "raising concerns that the platform is being used for the radicalisation of minors". It found limited evidence of extremists using gaming communities to groom new members, concluding that most used them to bond with fellow radicals and mobilise action.

Exit Hate, a British group that helps people leave extremist movements, tells The Independent that it is currently mentoring two people who were "groomed via online gaming".

A spokesperson said those people could not be interviewed because Exit Hate recommends its mentees wait 12 months before speaking to the press, but added: "Just over 70 per cent of people we talk to have been recruited online, with a growing number influenced by far-right gaming."

Although there isn't enough data to know how the pandemic has affected this picture, mainstream social networks have suffered sharp upticks in extremism. Moonshot, a British company that works with tech firms and government agencies to design and measure the performance of counter-extremism programmes, says it saw surge in extremist activity across the board.

"We have consistently found a connection between social isolation and extremism, so increased isolation during the pandemic, we believe, also made people more vulnerable," says Ross Frenett, Moonshot's co-founder and co-chief-executive, who has helped draft reports on extremism in gaming communities for the European Commission.

"The pandemic [also] allowed a number of different previously, loosely connected or unconnected ideologies to fuse. The fusion of some of the anti-vax conspiracy narratives with QAnon and neo-Nazi ideas – all that was supercharged during the pandemic."

‘When I heard about this, my jaw hit the floor’

For Dr Kowert, who is research director at the gaming-focused mental health charity Take This, says such research was an alarming wake-up call.

"The first time I talked to Alex about his research, my jaw hit the floor," she says. "A lot of times when you talk about extremism in games, the thing that people imagine is a swastika put in a Discord chat. They're not thinking about, actually, these networks are people are being recruited, groomed, and mobilised within these spaces."

While politicians and journalists have traditionally worried about the content of video games – fearing, for example, that bloody shooters would make their players more disposed to violence – Dr Kowert says the real danger is more subtle.

She criticises the medium for its historically "ethnocentric" worldview, with white player characters fighting stereotyped foreign enemies, but argues that such narratives provide useful rhetorical tools for extremists rather than priming players directly to accept dehumanising ideas.

She also distinguishes between people who play games – now a huge proportion of the rich world's population – and "gamers", which has become a distinct cultural identity. "My mom plays Wordle every day. If you asked her if she was a gamer, she would never, ever say she was," says Dr Kowert. "I have three small children, I haven't played a game properly in years, and I would absolutely say I am a gamer."

However, Dr Kowert believes that this sense of shared culture is part of what makes gamers vulnerable to radicalisation. For many, "gamer" is a strong identity that induces feelings of solidarity and self-sacrifice towards other members of the group. Some undergo a process of "identity fusion", meaning that their membership of the social group "gamers" becomes core to their fundamental self.

Although most research on identity fusion has looked at nationalist groups or military groups, Dr Kowert's research has founder that gamer identity fusion is correlated with alt-right identity.

She cites studies showing that social bonds between gamers tend to be closer, more intimate, and more durable than the looser companionship typical of other online relationships, in part because they are forged through simulated battles and struggles.

"Friendships in games are formed backwards," she told GDC. "They're emotionally jumpstarted by this shared activity. First trust is established and then you get to know someone, whereas traditionally you get to know someone and then later you can determine if you trust them... that is a potential vulnerability when it comes to radicalisation and recruitment."

Game companies may be exacerbating the problem

According to Mr Newhouse, the far right radicalisation playbook tends to follow three basic steps. First comes the "shotgun" phase, in which extremists blast out propaganda and provocations into gaming communities, often disguised as "edgy" or ironic humour. Their goal is both to normalise their ideas, blurring the lines between bystander and true believer, and reach individuals who might be predisposed to learn more.

Jim Whitley, a volunteer moderator for one of Reddit's major Second World War history boards, describes a similar dynamic playing out there. Neo-Nazis try various tactics to insert their ideas into discussion, from insincere "just asking questions" threads that "cloak one's opinions in questions that appear innocuous" to "indirect" propaganda arguments that disguise fascist apologia as historical scholarship.

"The best way to combat this sort of ideological intrusion is with active moderation and vigorous responses. A laissez-faire approach simply doesn't work, because the extremists care more and will coordinate their efforts," Mr Whitley tells The Independent. When moderators clock what's happening, the fascists sometimes unmask, hurling antisemitic and gendered abuse in private messages.

Then comes the phase of "social networking and identity creation", in which sympathetic users are sucked into deeper ties with extremists. These groups offer genuine support and community while encouraging members to undergo far-right identity fusion, moving into the third stage: "mobilisation".

Here, the most hardened and committed members become part of efforts to organise material actions for the cause, such as protests, rallies, skirmishes with anti-fascist activists, vandalism, harassment campaigns, or even shootings and terrorist attacks. Mr Newhouse has found probable such networks on Roblox, Steam and Discord.

This whole process is made easier by the proliferation of what Mr Newhouse calls "social hooks", meaning features that allow gamers to build networks together that can span multiple games and platforms. Groups, friends lists, alliances and feuds, and tie-ins between games and social networks are all tools that can be exploited by extremists, and all are becoming more common.

These features are hardly new, appearing in "massively multiplayer" Noughties games such as Everquest and World of Warcraft, but changes in the gaming industry have made them ubiquitous. Video games today are fully mainstream, and inescapable among Generation Z, while most of the biggest games are now both online and free to play.

Whereas in the Noughties most games were single player by default, with multiplayer bouts requiring special effort, it's now the norm for big titles such as Fortnite, Minecraft and Destiny to be continually connected to the internet, delivering an endless stream of new updates, interactions with other players, and opportunities to buy digital goods for real money.

"It's a matter of scale," says Mr Newhouse. "All these games are becoming more accessible, and at the same time bringing with them millions upon millions of more players. It's [at] the point where for a lot of people, the games are their de facto social platform – they're where they go to interact with the most.

"It's almost like the really die-hard World of Warcraft players are more the norm than the exception these days, because of how entrenched these games have become in the culture and how pervasive those persistent community-building features are throughout them."

'We're ten years behind where we should be'

Are the companies that host these communities doing enough? Mr Newhouse believes not, saying that "content moderation in games isn't as advanced as other forms of social media" and that Discord has repeatedly failed to spot servers that are "openly affiliated with extremist movements".

Moreover, he argues that many companies still treat the problem as one of content moderation – finding and removing content that breaks a set of rules – rather than of intelligence gathering and network-breaking, which requires different strategies.

Dr Kowert similarly says: "This is festering in gaming communities, and we're ten years behind where we should be in terms of how to combat it."

Mr Frenett believes the games industry is alert to the problem, but warns that companies need to match what bigger social networks are doing as best they can at their size. That means having some kind of dedicated intelligence capability, banning extremist activity even when it doesn't break the law, and building artificial intelligence to automatically detect signs of extremist organising, among other solutions specific to the type of platform.

"Platforms should proactively search for harms," he says. "They shouldn't sit around and wait for harms to be reported to them. Whatever your capacity, there is an ethical responsibility to ensure that the product that you're putting into the world is safe by design.

"We don't expect car companies to just put out unsafe cars, and then only make changes when people die. But far too often in the technology world, the idea is 'build it and they will come, and when there's complaints, we'll figure it out'.

"Maybe was excusable when the internet was in its infancy, but we've all we've all been around long enough now to know that if you're building a new platform, and it allows for social connection, it will be abused by disinformation actors, conspiracy theorists and terrorists."

Companies' efforts, and their openness in describing them, vary. Discord, Twitch and Microsoft, which owns Minecraft, have all joined the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism (GIFCT), a nonprofit founded by Facebook, Microsoft, Twitter and YouTube in 2017 to coordinate anti-terror efforts between tech firms.

As a condition of membership, all release regular transparency reports that say how much content they have taken down and in what categories, as well as how they find it in the first place. Roblox and Steam's parent company Valve are not part of GIFCT, although Roblox says it is "in dialogue" with the body.

In response to questions from The Independent, Discord and Roblox both said they had dedicated counter-extremism or counter-terrorism teams, though did not say how many moderators they have. Microsoft said it strictly forbids "terrorist or violent extremist content" but gave few details. Twitch and Valve declined to comment on the record.

A spokesperson for Discord disputed Mr Newhouse's characterisation, telling The Independent that it had investigated and taken action against the servers mentioned in the GDC talk. They said the company has a "dedicated counter-extremism sub-team" that works proactively to find radical networks before they are reported by users.

"It is Discord’s highest priority to ensure a safe experience for our communities, and we are continuously investing in our safety capabilities," the spokesperson said. "Our dedicated safety team uses a mix of proactive and reactive tools to keep activity that violates our policies off the service, including advanced technology like machine learning models."

The company has also begun taking users' offline behaviour into account when deciding whether its rules on extremism have been broken (Twitch has done the same). Any credible evidence of offline participation in known violent groups, or threats of violence, could lead to an online ban.

Roblox gave the fullest response. “We abhor extremist ideologies and have zero tolerance for extremist content of any kind on Roblox," said the firm's vice president of trust and safety Remy Malan. "Because of the swift, proactive steps we take, extremist content is extremely rare on our platform and therefore, for the vast majority of the Roblox community who do not seek out such content, it is very unlikely they would be exposed to it....

"We recognise that extremist groups are turning to a variety of tactics in an attempt to circumvent the rules on all platforms, and we are determined to stay one step ahead of them. We are deliberately agile in our efforts – we constantly strengthen the tools and filters we use to track down bad actors and expand the range of content blocked by our moderation systems."

He added that Roblox has "thousands" of content moderators who cover all hours, and uses artificial intelligence (AI) to scan "every single image, video, and audio file" uploaded by users. He also thanked Dr Kowert and Mr Newhouse for their work, and said the company is in "active dialogue" with them, GIFCT, and other organisations such as the ADL.

Gaming culture may be part of the solution

Content moderation alone can't dismantle extremist networks nor solve the underlying social or psychological problems that lead them to form. A lasting improvement might come from the same unique elements of gaming culture that extremists try to exploit.

"We do know that games offer a lot of positive social and emotional support," says Dr Kowert. "They are associated with reduced loneliness; they produce bonding and social capital... I've been friends with some of the people I play games [with] for decades..."

The question, then, is why this same bonding process leads most people into healthy, positive relationships and a minority into political extremism. One potential answer, which Dr Kowert is currently researching, is that high levels of harassment, hate speech, or toxic behaviour in a community make its members more likely to be radicalised in future, turning the process of identity fusion to bad ends.

Moonshot has found that, in Mr Frenett's words, "engaging hate speech is often an indicator that you're on the road to extremism". If so, gaming companies would need to see harassment and violent extremism as linked problems, adopting a coordinated approach to both.

Either way, Dr Kowert warns that researchers must reckon with the real needs people are seeking to fulfil when they join extremist communities. "What's really critical about these radicalisation groups is they absolutely make you feel welcome and that you belong," she says. "The valence of the conversation is obviously towards hate and violence, but they're there to make you feel good and make you feel included and make you feel special."

Mr Frenett argues strongly that games and gaming culture are part of the solution, saying there is no systematic evidence that gamers or gaming communities are at greater risk of radicalisation than any other group.

"There's been a sustained attempt for decades now to connect gaming with violence from groups like the National Rifle Association to deflect away from the idea that gun control [could reduce] mass violence, and unfortunately that perception of gamers as vulnerable in and of themselves has filtered through," he says. "It's frankly at best misguided, at worst incredibly dangerous."

Conversely, he thinks policy-makers should consider how gaming could help prevent radicalisation, saying: "People feeling connected, people feeling part of a group, people being able to express themselves: these are all the kinds of reasons that sports are very often used in preventing and countering violent extremism. Not nearly enough work has been done to use eSports in violence prevention work."

For Dr Kowert, the power of video games to forge close connections – for good or ill – reminds her of something her mother use to tell her as a child. "You are who you spend your time with," she says. "My mom's advice stands today."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks