228 were killed when Flight 447 crashed into the Atlantic. Their families could finally hear why

A Parisian court will hear conflicting expert testimony about who is to blame for the worst disaster in Air France’s history, but families of the 228 victims tell The Independent are determined to show the crash’s human toll, writes Bevan Hurley

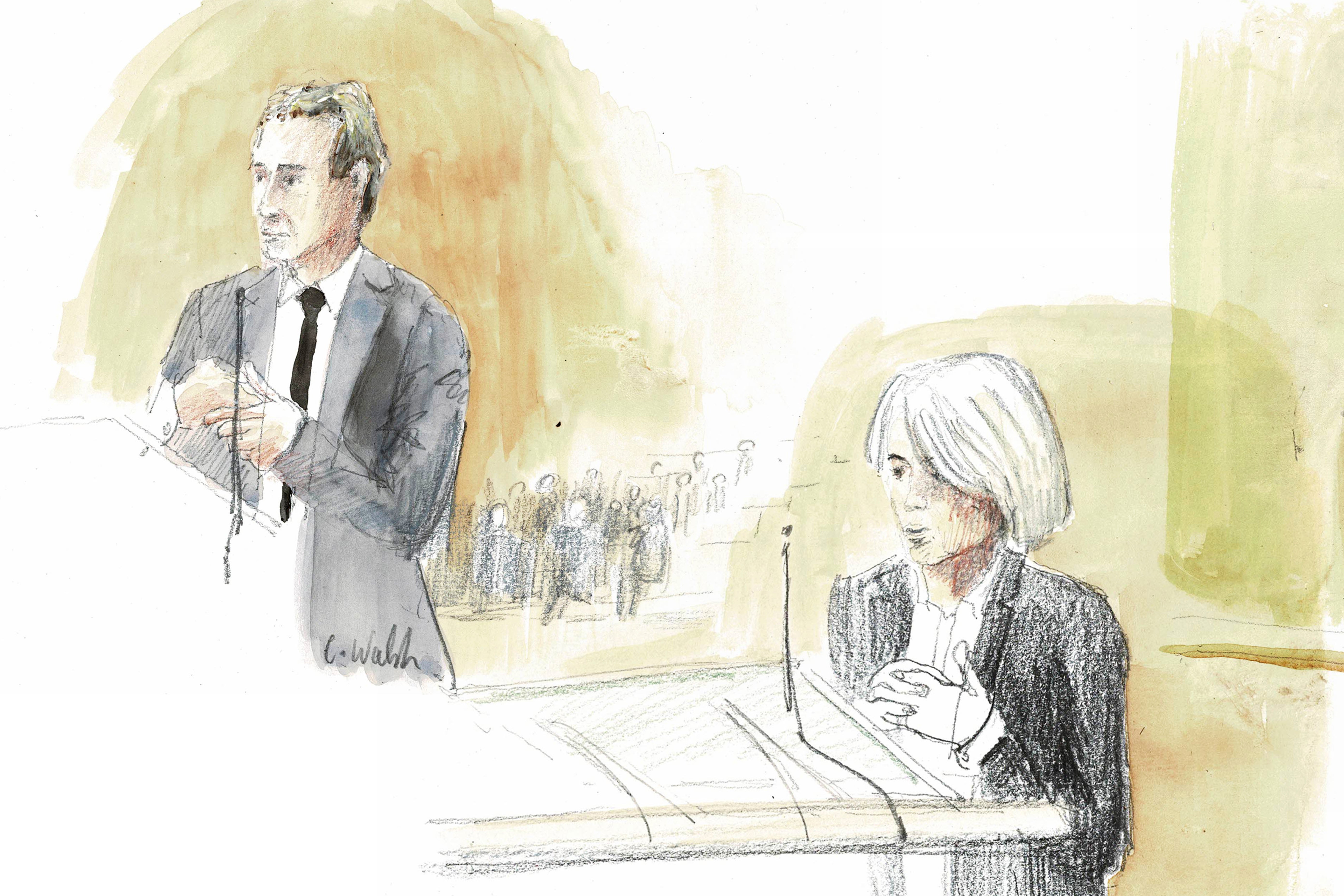

As the long-awaited criminal trial of Air France and Airbus began in a Parisian court last week, the CEOs of both companies took the stand as the names of the 228 victims of Flight 447 were read out.

Airbus’s Guillaume Faury offered his “deepest sympathy” to the distraught relatives who packed the court, while Anne Rigail insisted the French national airline “will never forget”.

The comments sparked furious scenes among relatives, who had fought for more than 13 years to see the two companies tried for involuntary manslaughter.

“Shame on you,” Philippe Linguet, who lost his brother Pascal in the crash, shouted at Faury as he spoke.

Linguet, 59, told The Independent that after years of denials and delays, the trial was an opportunity to show the human toll that the tragedy had inflicted on the 400 plaintiffs.

“We are determined to hold someone accountable and we will confront them,” said Linguet, vice-president of Entraide et Solidarité AF447, an association of families of the victims.

“We want them to listen to our grief, to listen to us talking about our 228 loved ones. They are still in our hearts, we miss them, we will never forget them.”

Air France and the A330 planemaker Airbus stand accused of a catalogue of errors that collectively doomed Flight 447, which crashed into the Atlantic Ocean on a Rio de Janeiro to Paris on 1 June 2009 during a violent tropical storm off the northeastern Brazilian coast.

An official report into the air disaster released in 2012 by France’s Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety found crucial speed and altitude sensors, known as pitot tubes, had frozen over due to ice crystals thrown up by the storm.

This disconnected the aircraft’s autopilot, leaving its crew to try to fly the plane with faulty navigation data, the report found.

The two-month trial is expected to focus on reports that Airbus had known since 2002 that the plane’s speed sensors were faulty.

It will also examine allegations that the Air France pilots were not trained on how to cope with sensor malfunction.

Along with hearing testimony from many of the relatives, parties will call their own specialist witnesses from the aviation industry, in what Linguet describes as a “fight between technical experts from the aeronautic world”.

“All different hypotheses will be on the table,” he told The Independent.

The facts of the crash have been pored over in countless articles, books, documentaries and investigations.

For the families, crucial warning signs that would have avoided the disaster were overlooked.

Linguet told The Independent that prior to the Air France tragedy, there had been dozens of incidents where Airbus planes had lost control of speed sensors due to icing.

Because those warnings had been ignored and the faulty pitot tubes not replaced by more robust ones, “228 families have been plunged into deep sorrow and pain”, he said.

Air France has compensated the bereaved families, and both companies face fines of up to 225,000 euros ($219,000) if convicted, a tiny fraction of both companies’ annual profits.

They have denied wrongdoing, and no individuals are on trial, so there is no risk of prison sentences.

But Linguet sees the trial as vital to avoiding future tragedies, and hopes the companies will be deemed “legal persons” who can be held criminally responsible.

Death spiral

Flight 447 vanished from radar over the Atlantic Ocean between Brazil and Senegal with 216 passengers and 12 crew members aboard a few hours after taking off from Rio on 1 June 2009.

A subsequent investigation found that the plane’s nose pitched upward before its engine stalled at 38,000 feet, sending it into an uncontrollable, three-and-a-half-minute spiral into the ocean.

A massive search and rescue was launched involving the Brazilian military and French nuclear submarines, and a week later the first bodies of passengers were recovered floating on the ocean.

It would take a full two years to locate the plane and its blackbox at a depth of 4,000m below sea level on the ocean floor.

Citizens of 33 countries were among the victims, including a professor, doctors, dancers, a member of Brazil’s former royal family, humanitarian workers and eight children.

Pascal Linguet, an executive at French electrical equipment company CGED, was accompanying nine company employees and their wives who were given tickets as a reward for winning an internal sales competition.

Cockpit recordings from the two black boxes confirmed that the failure of the aircraft’s speed detectors, or pitot tubes, triggered the accident.

Investigators also found that the captain of the Rio-Paris flight was away from the cockpit when the Airbus stalled for the first time, a detail revealed by The Independent in 2011.

Recordings from the cockpit showed the two co-pilots making increasingly desperate pleas for the more experienced captain to return to the flight deck.

But by the time he returned, the plane had already begun its death spiral.

In 2009, an investigation by the Associated Press found that Airbus had known since at least 2002 about problems with the type of speed sensors used on the jet that crashed, but failed to replace them until after the crash.

The accident led to major changes to pilot training and ushered in new regulations on airspeed sensors, including the banning of the Thales AA pitot sensor model used by on Airbus’s A330s.

The case has reportedly stoked bitter divisions between the two French firms over who was to blame.

Justice delayed

In 2011, the companies were placed under investigation as French prosecutors examined shortcomings in training and on-board safety systems that led to the crash.

That probe was halted in 2019 after prosecuters recommended dropping charges of negligence and manslaughter.

Under intense pressure from the relatives, the case was reopened by a public prosecutor in 2021.

In an interview with the AP, the head of the French victims association Daniele Lamy said the families were preparing to “have to unfortunately relive particularly painful moments”.

Linguet said the families simply wanted “justice and truth from this trial”.

“It is our duty in memory of the victims,” Linguet told The Independent.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks