First-time gun owners at risk of suicide, new study confirms

Experts say new evidence is more powerfully persuasive than any research to date

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The decision to buy a handgun for the first time is typically motivated by self-protection. But it also raises the purchaser’s risk of deliberately shooting him or herself by ninefold on average, with the danger most acute in the weeks after purchase, scientists reported on Wednesday. The risk remains elevated for years, they said.

The findings are from the largest analysis to date tracking individual, first-time gun owners and suicide for more than a decade.

The study, posted by the New England Journal of Medicine, does not greatly alter the prevailing understanding of suicide risk linked to gun ownership. Previous research had suggested a similarly increased risk, due largely to the ease of having such a lethal option at hand.

But experts said the new evidence is more powerfully persuasive than any research to date. The study tracked nearly 700,000 first-time handgun buyers, year by year, and compared them to similar nonowners, breaking out risk by gender. Men who bought a gun for the first time were eight times more likely to kill themselves by gunshot in the subsequent 12 years than nonowners; women were 35 times more likely to do so. (Male gun owners far outnumbered women owners in the study.)

“I find the work extremely compelling,” said Amy Street, a research psychologist at the National Centre for PTSD, VA Boston Healthcare System and Boston University School of Medicine. Ms Street did not contribute to the study, which was led by David Studdert, a professor of medicine and law at Stanford.

“We know women make more attempts than men, but they use less lethal means,” Ms Street added. “It makes sense: When women start using lethal means, you’re going to see this dramatic jump in rates.”

Historically, public health research on firearms has been limited by privacy issues and political opposition. Most previous studies were retrospective: post-mortem analyses of suicides that relied on incomplete information about gun owners and, for comparison, nonowners.

Mr Studdert’s study, which looked at deaths and gun ownership in California, overcame these obstacles. By California law, all legal gun sales must go through licensed dealers and be reported to the state’s Department of Justice. The department archives each transaction and includes more detail on the purchase than most any other state.

The research team integrated this information with two other sources: a California log of deaths determined to be suicides, which all states track to some degree; and voter rolls, which include about 60 per cent of adults in the state, or 26.3 million adults.

By linking individuals’ gun purchases to the voter registry and suicide data, the team was able to track individuals over time, from October 2004 to December 2016. The researchers checked gun purchases back to 1985 to make sure that individuals in the study were in fact first-time buyers. They also reclassified those who later sold their weapons as nonowners.

This left 676,425 people who bought their first gun during the 12-year period and kept it. The weapons were predominantly handguns, which are the method of choice in about three-quarters of suicides by firearm. California did not begin collecting data on rifles and shotguns until 2014.

The team tallied the suicides among new owners and nonowners, matched by age, gender and other similarities, and tested for a series of alternate possibilities, like whether owners were more likely to kill themselves by other means. They were not.

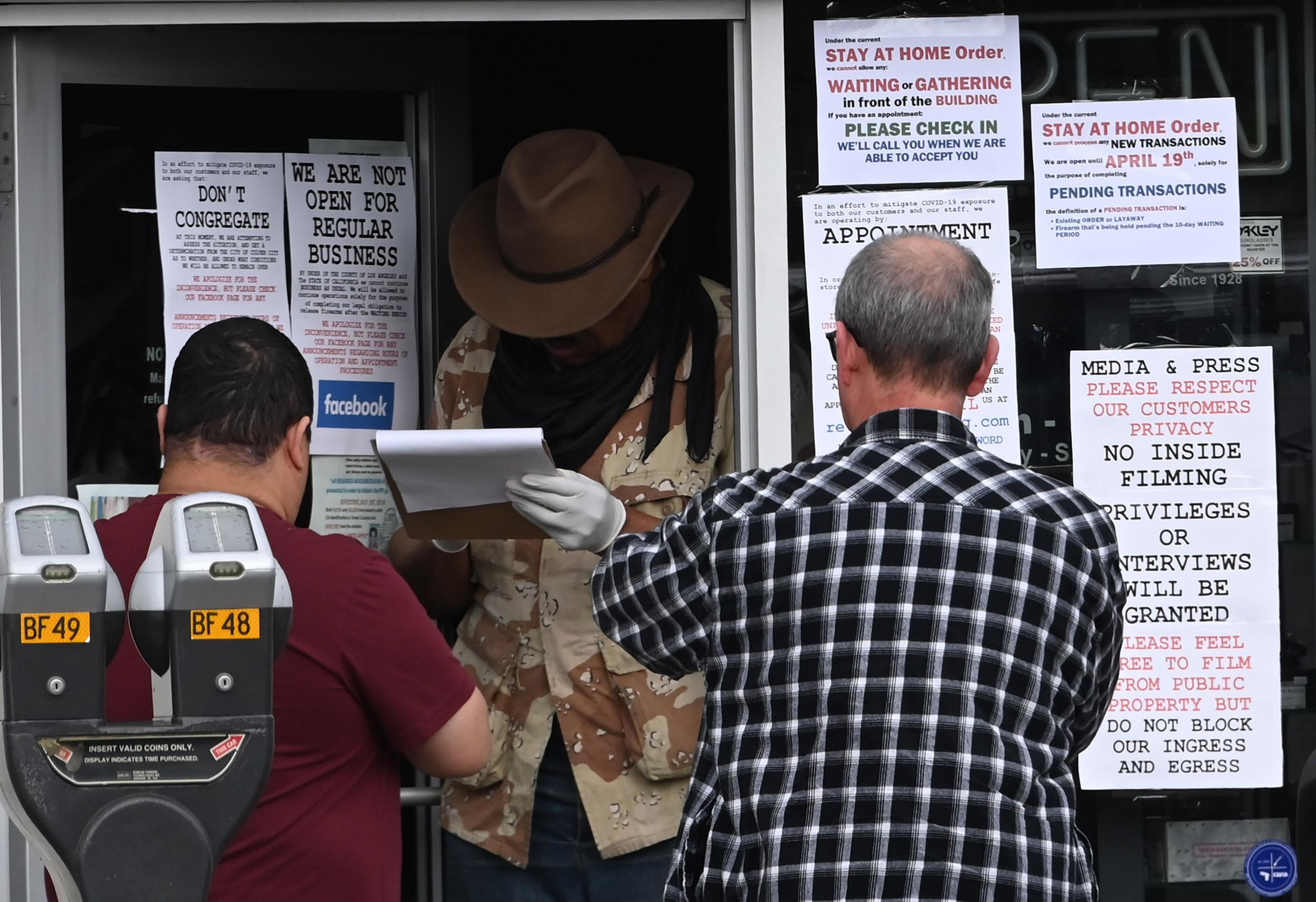

Another possibility was so-called reverse causation: that many buyers were bent on suicide before they bought the gun. The findings did provide some evidence of that. In the month immediately after first-time owners obtained their weapon (California has a 10-day waiting period), the risk of shooting themselves on purpose was nearly 500 per 100,000, about 100 times higher than similar nonowners; after several years it tapered off to about twice the rate.

“We sure do see evidence that people went to get the gun because they had planned to take their own lives,” Mr Studdert said.

The risk of suicide remained elevated over the entire 12-year duration of the study, and it was in this longer period after the first month that most of the suicides – 52 per cent - occurred. “During this period, the gun acts much more like an ambient risk — it’s always there,” Mr Studdert said.

The majority of people who attempt suicide do not die; attempts outnumber completed acts by about 8-1. Those who do make an attempt are at greater risk of trying again later, compared to those who have not, studies have found. Still, fewer than 10 per cent of those who make an attempt will subsequently go on to complete the act, said Dr Matthew Miller, a professor of health sciences and epidemiology at Northeastern University and an author on the study.

“Many suicide attempts are impulsive, and the crisis that leads to them is fleeting,” Dr Miller said. “The method you use largely determines whether you live or die. And if you use a gun, you are far more likely to die than with other methods, like taking pills. With guns, you usually do not get a second chance.”

New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments