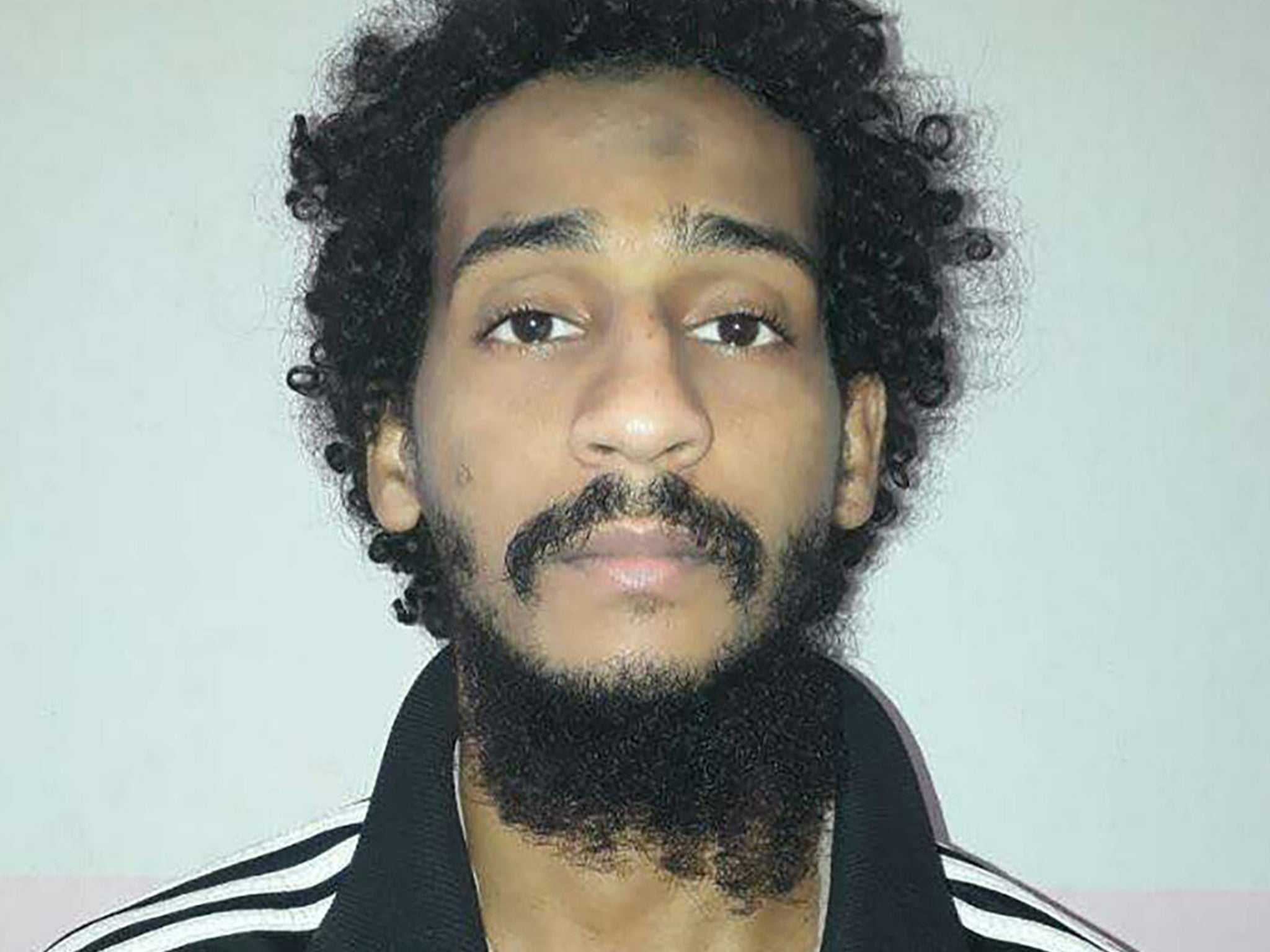

‘Relentless abuse and torture’: Prosecution wraps evidence in trial of British Isis fighter as jury deliberates

El Shafee Elsheikh denies being one of a kidnapping group nicknamed the ‘Beatles’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A jury has begun deliberation in the trial of El Shafee Elsheikh, a British Isis fighter who is accused of involvement in a vast hostage-taking scheme that caused the deaths of British, American and Japanese hostages.

Elsheikh, 33, is the most high profile member of the notorious terror group to stand trial in the US. The Sudanese-born Londoner is alleged to have been part of an Isis hostage-taking cell operating in Syria that was dubbed the Beatles by their captives.

That kidnapping scheme led to the killing of American journalists James Foley and Steven Sotloff, and aid workers Kayla Mueller and Peter Kassig. The indictment also holds him responsible for the deaths of British aid workers David Haines and Alan Henning, and Japanese journalists Haruna Yukawa and Kenji Goto.

In closing arguments on Wednesday, prosecution attorney Raj Parekh said Elsheikh had engaged in “systematic, premeditated, and relentless abuse and torture” of the hostages under his watch.

“We have built you a mosaic of evidence. Some pieces may be bigger than others, but together, they form a clear and complete picture,” he added.

Over three weeks, the jury heard evidence from former hostages, families of his alleged victims, another former Isis fighter and US officials who interviewed Elsheikh following his capture.

The so-called Beatles, whom the prosecution named as Elsheikh, Alexanda Kotey and Mohammed Emwazi, stand accused of at least 26 kidnappings in Syria between 2012 and 2015, most of them Westerners. Emwazi, who was killed in a drone strike in 2015, was thought to be the ringleader of the group and carried out the executions of hostages. Kotey pled guilty in September 2021 to his involvement in the murders of Foley, Sotloff, Meuller and Kassig, and is due to be sentenced next month.

“The evidence demonstrates that they grew up together, radicalised together, fought as high-ranking Isis fighters together, held hostages together, tortured and terrorized hostages together, and after Emwazi was killed, Elsheikh and Kotey were ultimately captured in Syria together,” Mr Parekh said.

Elsheikh’s defence team has denied that he was a member of the Beatles, and instead claimed he was “a simple Isis soldier.” But his own words — information he corroborated in interviews with media outlets while in detention — formed a crucial part of the prosecution’s evidence.

Throughout the trial, the prosecution has interspersed testimony from witnesses about their time in Beatles captivity with interviews given by Elsheikh to various journalists.

In those interviews he named some of the western hostages who he watched over, admitted to collecting emails for use in ransom notes, and to beating them.

“I’ve hit most of the prisoners,” he told one interviewer, in a video shown to the court. “I did have transgressions. I did transgress physically,” he said, when asked about the beatings.

He also tried to justify his ill-treatment of prisoners by claiming it was necessary to keep prisoners in line because they didn’t have a proper facility to prevent them from escaping.

“Subduing prisoners is used as a preventative of escape,” he said.

Elsheikh’s defence team tried to have those videos thrown out of evidence, suggesting that he was forced by his Kurdish guards to give confessions during his detention. That motion was denied by the judge, who claimed wellness checks by US officials who visited him at the jail showed no signs of mistreatment. Elsheikh’s lawyers said during the trial that he lied about being a Beatle in the interviews so he could be arrested by US law enforcement instead of being transferred to Iraq, where Isis fighters were being handed death sentences in speedy trials.

During closing arguments, Mr Parekh said those clips were a key reason why the jury should find Elsheikh guilty.

“Let’s start with the most obvious reason to conclude that Elsheikh was one of the three notorious Beatles: he brazenly told you so himself,” he said. “You’ve watched video clip after video clip of interviews in which the defendant admitted to and described in granular detail his integral and essential participation in the crimes we have charged here, which form the horrendous criminal conduct in this case.”

Defence attorney Nina Ginsberg said Elsheikh could only be found guilty of one of the eight counts in the indictment, which was providing material support to a terrorist group, but added there was not enough evidence to prove he was part of the hostage taking operation.

“As hard as the government tried, It did not prove that Mr Elsheikh was one of the Beatles,” she said.

The jury heard from numerous former hostages of the Beatles, who gave harrowing testimony about their time in captivity.

Federico Motka, a former hostage of the Beatles, described how he and his fellow captives were given dog names by their jailors, who subjected them to “regime of punishment” for perceived transgressions.

The Italian aid worker, who was held by Isis for 14 months, said the British jihadists seemed at times to revel in their brutality.

“They played lots of games with us,” he said. “They gave us dog names and told us that if they called us day or night we had to respond.” The punishment for failing to do so was a beating, he added.

Mr Motka also described an incident in which one of the group lost their temper with him during a late night trip to the bathroom.

“Something I said triggered them. They came in 20 minutes later and started to beat and kick me,” he said. “They called me a posh wanker because I went to boarding school.”

After what Mr Motka described as a “calm” first few weeks of captivity, that changed when he was accused of trying to escape from jail and talking to a Syrian captive. From then on, he said a “regime of punishment” was introduced.

Mr Motka said there was a certain protocol implemented by the Beatles during their captivity: detainees had to kneel and face the wall when they entered the cell. The Brits wore full balaclavas with only the eyes showing all the time. In the courtroom, Elsheikh watched the testimony while wearing a mask that covered the bottom half of his face.

Didier Francois, a French journalist kidnapped in 2013, gave similar testimony, describing the Beatles as “extremely violent and always sadistic.”

The jury also heard emotional testimony from several family members of hostages that were eventually executed by Isis in gruesome propaganda videos.

Diane Foley, the mother of James Foley, was notified of his killing in a phone call from another journalist in August 2014, nearly two years after his kidnapping while on assignment in Syria.

“I didn’t believe it. It sounded too horrific,” she said. “I hoped it was a cruel joke.”

Earlier, she told the court that James — whom she referred to by his nickname, Jim — had put himself in danger “so that the world would know what was going on in Syria.”

“He was aware of the danger, but said he had promises to keep,” she said.

She described the desperate lengths the family went to in an effort to secure James’ release. The FBI had told them not to talk to the media, but she said she and her husband John became “frantic” and decided to hold a public press conference in which they appealed to his captors.

The court later heard from the mother of American aid worker Kayla Mueller, who recounted the great lengths she and her husband Carl had gone to in their efforts to free their daughter.

One such attempt included a video message from the two of them to Abu Bakr al Baghdadi, who was then the leader of Isis, which they sent in an email to Kayla’s captors.

“I am coming to you with a mother’s heart, for the love of her daughter,” she said in the video, which was shown to the jury on Tuesday.

“Kayla is not your enemy,” she added. “I ask from her mother’s heart that you show your mercy and release our daughter.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments