Life in Walmart El Paso store before the mass shooting shines a light on why it was targeted

Many targeted by hate-filled gunman just yards from US border were Hispanic and Latino people going about their daily shopping alongside Americans

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Two nations physically and culturally come together in El Paso. The bustling Walmart on the city’s east side, just minutes from the border with Mexico, exemplified those ties.

The store was a border version of Middle America: A large number of Mexican-American families from El Paso crowded into the megastore daily for inexpensive groceries and, late in the summer, back-to-school supplies.

Almost as often, families from Mexico drove across the international bridge to buy bargain TVs, cartons of nappies and discount clothing.

It was one of the company’s top 10 in America: Where most stores of its kind average 14,000 customers a week, the El Paso Walmart, a retail analyst said, saw 65,000.

Its racks are stocked with Mexican football jerseys, cans of chillies and salsa and Mexican flags, folded beneath the American and Texas flags on display. The pharmacy’s staff members are fully bilingual.

“It really does feel like a United Nations store,” said Burt Flickinger, a retail consultant who has visited and studied the store.

This is the border as it is lived everyday, far from the heated national debate over immigration. Children come and go across the international boundary for school, others come for jobs and shopping.

It was in this Walmart, on a sunny Saturday morning, where a white gunman angered by what he called the “Hispanic invasion of Texas” chose to carry out a horrific act of violence.

Disturbed gunmen have previously targeted American Jews, African Americans, Muslim-Americans, gay Americans and American journalists.

Authorities say the El Paso gunman, identified as Patrick Crusius, 21, targeted Mexican and Mexican-American shoppers and workers in the attack on Saturday, killing 20 people and wounding 27 others.

While there have been numerous Hispanic victims in several of the mass shootings that have shocked the nation in recent years — including the Pulse nightclub attack in Orlando, Florida, in 2016 — the massacre in El Paso was the deadliest anti-Latino attack in modern US history.

The manifesto that a federal law enforcement official said Mr Crusius wrote and posted online minutes before the shooting made his anti-immigrant beliefs clear.

He wrote that immigration “can only be detrimental to the future of America,” and bemoaned a future in which Hispanics would take control of the local and state governments, “changing policy to better suit their needs”.

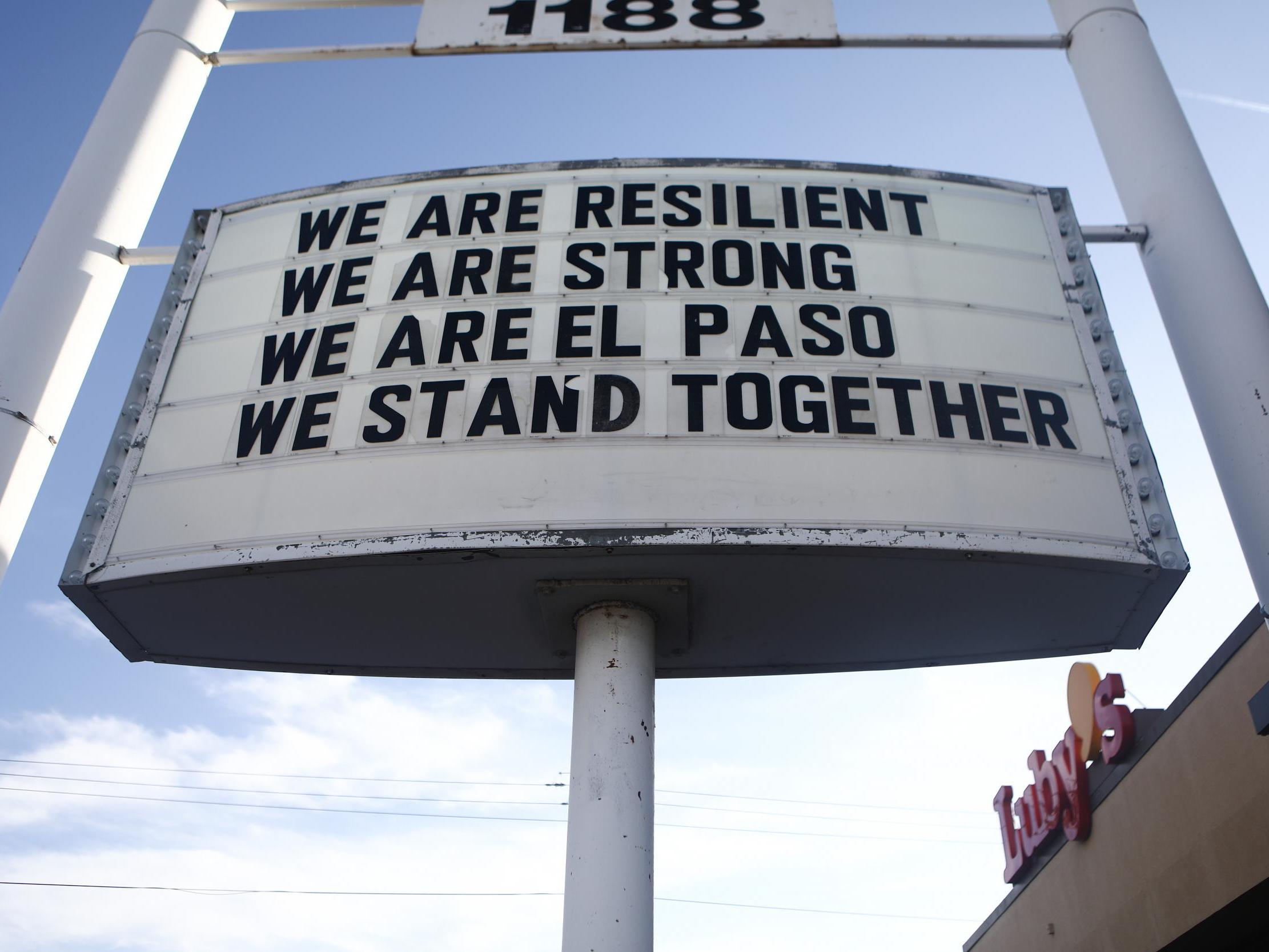

The apparent anti-Latino motive behind the attack stunned residents and officials, who saw the nation’s fraught debate over culture and immigration erupting with sudden violence in a city that had been both a focal point of immigration and a place — like many border towns — where the notion of immigration and national identity had rarely felt divisive.

“What was most shocking to me is not that it was a mass shooting but the motive, the fact that he specifically targeted Mexican-Americans and Hispanics,” said Gilda Baeza Ortega, 67, a librarian at Western New Mexico University who was in El Paso visiting her parents. “He came here for us.”

Across the country, many Latinos were describing the targeted killings as a 11 September moment, and the FBI’s announcement Sunday that it had opened a domestic terrorism investigation only reinforced that belief, especially in a city that is 80 per cent Hispanic.

“This Anglo man came here to kill Hispanics,” El Paso’s sheriff, Richard Wiles, said. “I’m outraged, and you should be, too. This entire nation should be outraged. In this day and age, with all the serious issues we face, we are still confronted with people who will kill another for the sole reason of the colour of their skin.”

Before the attack upended the sense of normalcy in El Paso, the Walmart and the shopping area surrounding it lured many people from across the border, as well as many El Paso residents looking for something to do on a weekend afternoon.

People from both countries would go to new releases at a cinema not far from the Walmart, shop for discount clothing at a nearby Ross Dress for Less or stop in for happy hour at Hooters.

Texas has long been a state where Hispanics have shaped and in many ways defined what it means to be Texan. But in recent years, the old white Texas and the new Hispanic Texas have repeatedly clashed.

Some of this tension involves who gets to tell history. Activists and scholars have begun focusing on the legacy of racist campaigns of terror against Latinos in this part of the West, including the killings a century ago of Mexicans by lynch mobs made up of Anglos.

Going back further in the debate over any “invasion of Texas,” historians note that it was actually carried out by Anglo slaveholders who migrated to the region in the 19th century when it was still part of Mexico, then seceded in 1836 and enshrined white supremacy in the first Texas Constitution.

The more recent clashes have led not only to years-long court battles but also to physical confrontations between white and Hispanic politicians on the floor of the Texas House of Representatives.

White Republican officials in Texas have publicly expressed alarm about what they describe as an “invasion” of migrants spreading disease at the Texas border.

El Paso residents have now seen the most hateful parts of the debate bringing violence to their doors.

Adriana Ruiz was among those who left flowers, having picked up a bouquet from another Walmart in El Paso after church.

“I just...” she said, her voice trailing off. “Right now, my heart is broken.”

Ms Ruiz, 50, said she was pained by the animosity that had surrounded the national debate about El Paso as it became a ground zero of sorts in recent months as migrants came rushing in from Central America.

A hateful act seemed like such a stark contrast to the vibe and texture of the city where she was born and raised. She remembered going to Ciudad Juarez in Mexico on Saturdays with her mother, grandmother and aunts to go shopping.

“No matter who it is,” she said. “We make them feel at home.”

The shooting, she said, showed that a toxic environment outside El Paso was finding its way into the city. She heard it in the remarks about life in the city that did not reflect what she knew, especially those from Donald Trump, the US president.

“That is something that came from the top,” Ms Ruiz said, referring to the frequent portrayal of the border as a place of crisis that was threatened with invaders from outside.

“It’s idiotic,” she said, conceding that her anger had left her stumped for the right words. “I want to say some harsher words, but it’s not right."

Larry Scott, 40, said he had been in the Walmart on Saturday morning, several hours before the shooting. He had gotten two new tattoos on his left arm recently, including one of the Monopoly man holding a bag of money, and he needed ointment.

When he heard about the attack, Mr Scott, who said he serves in the Army and is stationed at nearby Fort Bliss, felt an urge to do something, to somehow pitch in. He came back to the store Sunday, but that offered little consolation.

El Paso was not his hometown. He was originally from Dallas, he said. Yet he had grown attached to the city.

“It’s not a big city,” he said. “But it’s our home. I’m hoping this makes El Paso stronger.”

The Walmart where the shooting occurred lies on the east side of El Paso along Interstate 10, near a number of hotels, chain restaurants and a mall.

Aside from the wares that are aimed at Mexican shoppers, it resembles hundreds of other Walmarts across America. The store does not sell guns, but does sell ammunition, a Walmart spokesman, Randy Hargrove, said.

On Sunday, the store remained blocked off by police officers who continued to collect evidence of the massacre inside. The parking lot was still packed, with the same cars that had been sitting there since the shooting the day before.

A steady line of cars drove by, some with cameras pressed to their windows. One man walked up, stood silently for a moment, made the sign of the cross and walked away.

New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments