Cuba-US relations: How one Caribbean island stood up to Uncle Sam and became the home of radical chic

It had a romantic pull, a state ruled by men who still dressed like revolutionaries, and which defied the American behemoth

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It’s been 50 years and three months since Bob Dylan released his album, Another Side of Bob Dylan, which included the track “Motorpsycho Nightmare” and the lyric:

“I had to say something to strike him very weird

So I yelled out ‘I like Fidel Castro and his beard’.”

Dylan was not offering a serenade to Cuban socialism: he was satirising the paranoia that infected right-wing US opinion about Castro. By 1964, it was cool to be relaxed with what was happening in Cuba, though it was another four years before the island became a place of pilgrimage for young Western socialists. What turned Cuba into a left-wing cause was the violent death, in Bolivia, of Che Guevara – whose name was barely known in the West while he lived. His execution made an international celebrity out of a 26-year-old French journalist, Regis Debray, who had been in Havana studying the regime and had written a book, entitled Revolution in the Revolution?, in which he implied that Soviet-style communism had calcified and that the future was in the hands of guerrilla fighters such as Castro and Guevara.

Debray went to Bolivia with Guevara, was caught and sentenced to 30 years. He was released after an international campaign led by eminent French intellectuals.

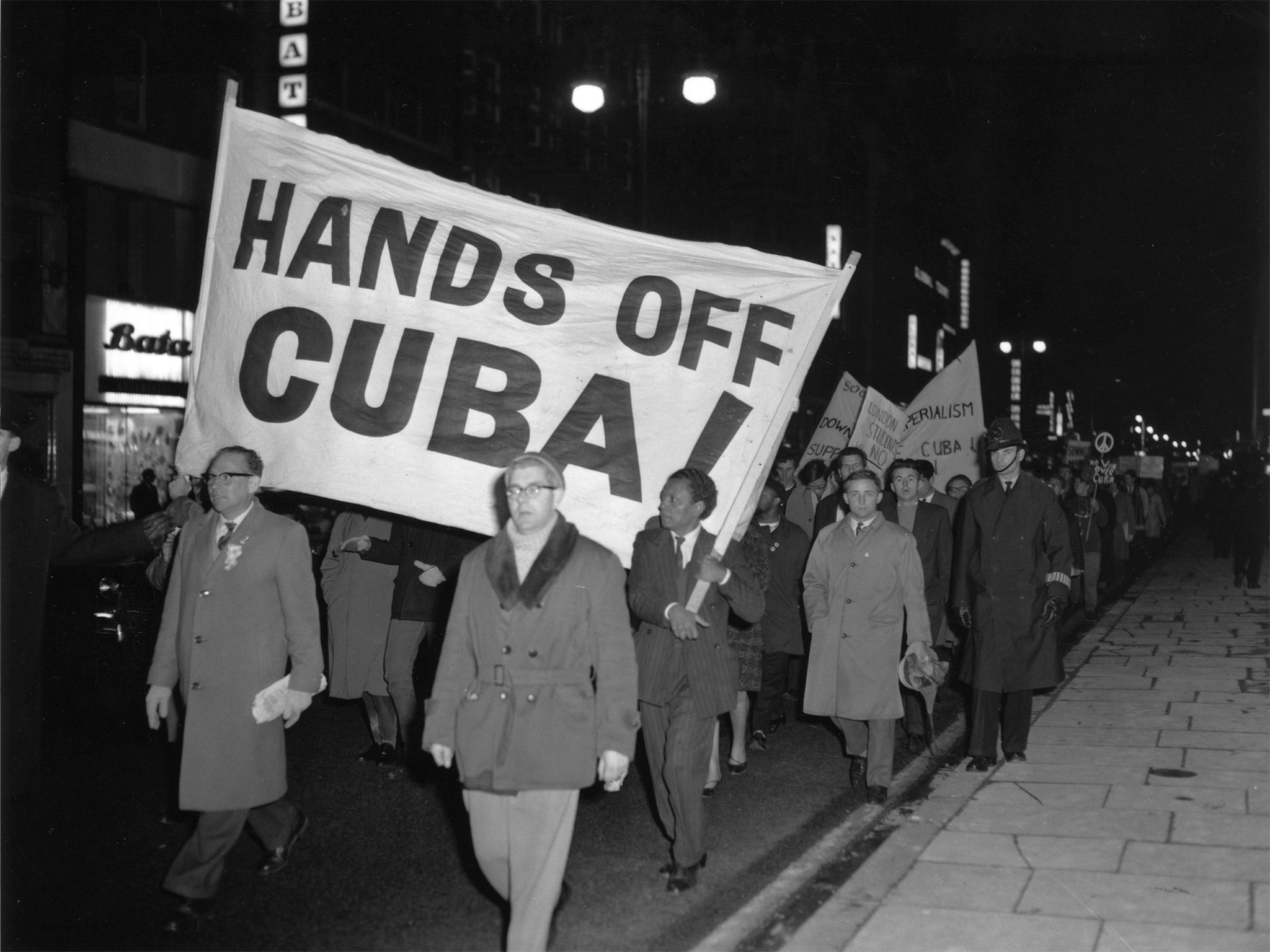

This was in 1968 – the year of demonstrations against the Vietnam War in every major city in the West. The young demonstrators were not generally attracted by Soviet communism, especially after the old men in power in Moscow sent the Red Army to crush an experiment in humane communism in Czechoslovakia. Cuba had a more romantic pull, an island state ruled by men who still dressed like revolutionaries, and which defied the American behemoth. Guevara, in particular, became a left-wing icon. A photograph of him in revolutionary garb, with a cap over his long unruly hair, was on posters, T-shirts and mugs, until his face was almost as recognisable as John Lennon’s. Even Hollywood cashed in, with a 1969 film starring Omar Sharif as Guevara.

In the mid-1970s, there was a controversy in the UK over whether young Britons should take part in a World Youth Festival in Havana in 1978. The event attracted many who would be prominent in later life. The future Home Secretary, Charles Clarke, was a representative on the organising committee and, despite complaints, the British Youth Council sent a delegation chaired by Trevor Phillips, later famous as a broadcaster and head of the Equalities Commission. The delegation’s deputy chairman was a 23-year-old Peter Mandelson.

When Ken Livingstone led the Greater London Council in the 1980s, he would receive an annual gift of Cuban rum in recognition of his outspoken condemnation of the US blockade. But by the 1980s, some of the glitter had left the Castro regime as a dictatorship closely allied with Moscow. It was outshone by the more democratic Nicaraguan revolution. There was a second wave of empathy with Cuba from 1997, when an exceptionally gifted group of ageing musicians came together and released an album entitled The Buena Vista Social Club – but it was the island and its culture rather than its calcified revolution that fascinated people this time around.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments