Seven murders by cyanide-laced Tylenol will never be solved. But the prime suspect’s death brings justice

After a joint FBI task force was unable to pin the 1982 Tylenol murders on prime suspect James Lewis, special agent Roy Lane was coaxed out of retirement to carry out a daring undercover mission. He tells Bevan Hurley Lewis’ death this week ‘puts the pursuit of justice to an end’

Roy Lane put away mobsters, judges and even a former Illinois governor during a storied 26-year career in the FBI.

For the retired special agent, the death of Tylenol murders suspect James Lewis at his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, this week at the age of 76, marked an unsatisfying end to the pursuit for justice he had dedicated half his life to.

“James Lewis’ death ends a lifetime of cruelty to others, and the compulsive need for revenge,” Mr Lane, 75, told The Independent.

In 1982, Mr Lane was assigned to a joint FBI task force of more than 100 law enforcement personnel investigating the poisoning deaths of seven Chicago-area residents.

On 28 September that year, the first victim Mary Kellerman, 12, was hospitalised after taking a capsule of Extra-Strength Tylenol, an acetaminophen manufactured by Johnson & Johnson.

The seventh grader died the next day.

Six adults would take the contaminated pills on 29 September, including three members of the same family, Polish immigrant Adam Janus, 27; his brother Stanley Janus, 25; and Stanley’s wife Theresa Janus, 20.

Mary McFarland, Mary “Lynn” Reiner, Paula Prince would all die within a day of consuming the toxic capsules.

The deaths of young mothers, fathers and children just starting out their lives were “heartbreaking”, Mr Lane said. “Each one was just awful.”

The mysterious deaths sparked a wave of terror across the United States, and doctors and law enforcement were initially baffled.

Helen Jensen, a public health nurse in Arlington Heights, was the first to suggest it could have been poisoning due to tampering with medicine bottles.

She visited the Jamus’ household and found a Tylenol bottle and a receipt, and testing on the remaining capsules revealed that they contained nearly three times a fatal dose of cyanide.

Ms Jensen told the Associated Press in an interview this week she was initially laughed at by investigators for suggesting the capsules had been deliberately tampered with.

“I was a woman and I was a nurse,” she said. “I understood the attitudes of that time. But I was proven right by the next day.”

On 5 October, Johnson & Johnson ordered a nationwide recall of more than 31 million bottles of Tylenol in circulation. Investigators rushed to remove the capsules from homes and off shelves.

The panic led to widespread changes to the way prescription drugs were packaged, and led the Food and Drug Administration to introduce anti-tampering features such as foil seals to packaging that remain standard.

In 1983, Congress passed the “Tylenol bill” making it a federal offence to tamper with packaging.

‘Halloween was cancelled’

Mr Lane remembers the sense of panic that spread through the nation that October.

“People were so afraid, Halloween was cancelled that year in most communities,” he told The Independent.

“From then on, people were warned to check their kids’ candies after coming back from trick or treating.”

The early investigation was hamstrung by distrust and rivalries between the Chicago Police Department and FBI, according tothe 2022 Chicago Tribune podcast Unsealed: The Tylenol Murders.

Law enforcement called on the FBI’s then-nascent Behavioral Science Unit, established in 1972, to try to build a picture of a suspect seemingly hellbent on committing mass murder.

Mr Lane told The Independent that the expert profilers suggested the person they were looking for would be experiencing a sense of “euphoria” at the global attention.

A few days after the murders, Johnson & Johnson received a one page, handwritten letter written in all caps demanding $1m to “stop the killing”.

“As you can see, it is easy to place cyanide (both potassium & sodium) into capsules sitting on store shelves,” the letter read.

“If you don’t mind the publicity of these little capsules, then do nothing. So far I have spent less than $50, and it takes me less than 10 minutes per bottle.”

After a nationwide manhunt, the letter was traced to James William Lewis, a conman who had multiple aliases and had been implicated in the 1978 murder of a Kansas City businessman.

Mr Lane told The Independent officials obtained a warrant for Lewis’ arrest on 11 October. He was arrested two months later after a lengthy cat and mouse game in December.

Lewis was described as a “chameleon” who had moved from state to state by police, using at least 20 aliases to work as a computer specialist, tax accountant, importer of Indian tapestries and pharmaceutical salesman, the Associated Press noted in an obituary.

Lewis had lived in Illinois before moving to New York with his wife LeAnn in the fall of 1982. He stood trial in 1983 on the extortion charges, and was convicted and sentenced to 20 years in prison.

Officers believed Lewis wanted to avenge the death of his daughter Toni, who died in 1974 aged five after sutures made by a Johnson & Johnson subsidiary that were used to fix her congenital heart defect had torn.

Lewis gave investigators a detailed account of how the killer could have carried out the poisoning, and while he remained the prime suspect in the murders, he was never charged, and the case remains officially unsolved.

‘The euphoria diminishes’

With the prime suspect in the Tylenol murders behind bars for extortion, the FBI continued to pursue leads in the case.

Then, out of the blue, Lewis contacted Mr Lane saying he wanted to be involved in the investigation.

“We had already been apprised by the FBI behavioural science unit that at that time the person was having euphoria about all the attention that was going on,” Mr Lane said.

“As time goes on, the euphoria diminishes, and the way they can recapture that euphoria is to contact one of the investigators, and want to be involved in the case itself.”

In an interview this week, Mr Lane said Lewis had waived his rights to self-incrimination while providing information that seemingly only the killer would have known.

He recalled being struck by Lewis’ odd behaviour.

“I was told that he would laugh at the wrong times, cry at the wrong times, and that’s exactly what he did. He wanted information about the case, and he wanted to become involved in solving the case,” Mr Lane said.

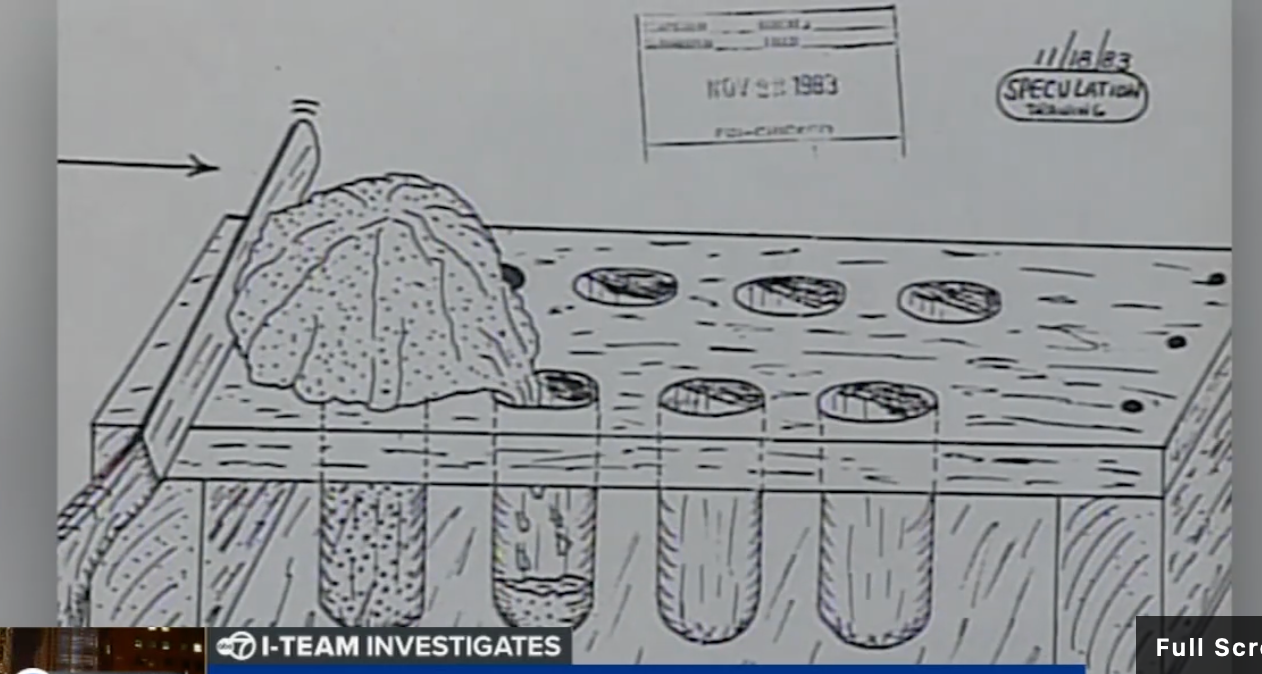

Mr Lane wouldn’t go into detail about what Lewis told him. But in a 1992 jailhouse interview with ABC 7 Chicago, Lewis described in detail how the killer would have used a pegboard to drill holes into the Tylenol capsules and inject them with deadly cyanide.

“There were certain statements that were made, and drawings that were made, that were quite incriminating,” Mr Lane told The Independent.

“He loved the attention. He didn’t care if it’s good or bad.”

Lewis stopped talking to the FBI after they refused to grant him immunity.

Lewis was released from federal prison in 1985, and moved to Massachusetts with his wife.

Stoking a ‘battered ego’

Mr Lane retired from the FBI in 1996 and moved into a job in private security.

A decade later, he received a call from the head of the FBI’s Chicago office.

The bureau had set up a second task force to examine fresh evidence in the case, and Lewis remained their prime suspect.

At the time, Lewis was in jail in Massachusetts on charges of kidnap and rape of a neighbour who he had been in a business dispute with.

He spent three years in custody, and was released in 2007 when prosecutors dismissed the charges on the day his trial was due to begin after the victim refused to testify.

Mr Lane told The Independent he was contracted to work on the sting operation by the FBI, but was unable to discuss details, citing the need to preserve operational security.

But some elements of the elaborate plot were revealed by the Chicago Tribune in their 2022 investigation, and by Lewis on his personal website.

According to both accounts, Mr Lane introduced Lewis and his wife LeAnn to a woman named Sherry Nichols, telling them she was an investigative reporter who was working on a book about the Tylenol murders.

In reality, Nichols was an FBI agent working under an assumed identity.

The FBI agents told Lewis they had identified a new suspect, and needed his help with the investigation that would clear his name.

Lewis was writing a novel at the time titled Poison! The Doctor’s Dilemma, and the agents reportedly offered to help.

The book, which Lewis self-published in 2010, was about a “rogue Government employee” named Agua Naranja who found himself at the centre of a mass posioning event in the Chicago area.

Lewis claimed in a lengthy spiel that on his website that the FBI tried to “lead and prod” him getting his protagonist to confess to the Tylenol killings.

“For 18 months, Roy Lane and Sherry Nichols, acting in cahoots, stroked my battered ego, wined and dined my wife and me at expensive restaurants, and tried to get both of us tee-toddlers drunk,” Lewis wrote.

“They gave me money to buy a laptop computer, flew me at govenment expense to Chicago, New York and Joplin, Missouri, then back to Boston, put me up in expensive hotels and paid me thousands of dollars, all while trying to manipulate me into implicating myself in mass murder in my own novel.”

Lewis claimed he had endured “nearly 40 years of being publically vilified in the press worldwide as the prime Tylenol mass murder suspect”.

Mr Lane would later tell the Tribune Lewis’ account was about 50 per cent accurate.

Police records obtained by the news site stated that the agents had worked closely with FBI criminal profilers on the sting.

Agents from the second FBI task force closely monitored the operation as Mr Lane and “Ms Nichols” took the Lewises on trips to New York and Chicago.

They returned to a Walgreens in Chicago where one of the victims, Paula Prince, had purchased the deadly Tylenol capsules.

According to police records obtained by the Tribune, Lewis walked straight up to where the poisoned bottle had been kept years earlier.

At a Chicago hotel, Mr Lane reportedly confronted Lewis with a major discrepancy in the timeline of his story. He had maintained at his extortion trial that he had taken three days to write the threatening letter to Johnson & Johnson.

However, the first media reports emerged about the Tylenol poisonings on 30 September. And the FBI later determined that the letter was sent on 1 October.

Lewis blamed a “faulty memory” on the problematic timeline.

‘Yes, I am a killer’

On 4 February 2009, the FBI executed a search warrant on Lewis’ home seizing computers and boxes of material.

Among the items taken was a handwritten note stating: “Yes, I am a killer but I got 10 good reasons”, the Tribune reported.

In the document, Lewis reportedly wrote that the “reasons” listed included “to protect my family” and “to teach a lesson.”

Authorities had long suspected revenge as a potential motive for the killings.

Lewis’ five-year-old daughter Toni had died after sutures used to fix her congenital heart defect had torn. He apparently blamed Johnson & Johnson for the death.

The investigation remained active for years, and Lewis was questioned as recently as September 2022 over the poisonings.

Lewis had also been in serious trouble with the law on previous occasions.

In 1978, he was charged in Kansas City, Missouri, with the dismemberment murder of Raymond West, 72, who had hired him as an accountant, the Associated Press noted in its obituary.

The charges were dismissed because West’s cause of death was not determined and some evidence had been illegally obtained.

Lewis was convicted of six counts of mail fraud in a 1981 credit card scheme in Kansas City, accused of using the name and background of a former tax client to obtain 13 credit cards.

He continued to deny any involvement in the Tylenol murders right up until his death.

In one of his final interviews last year, he told Chicago Tribune reporters: “Have you been harassed over something for 40 years that you didn’t have anything to do with?”

Lewis, 76, was found unresponsive at his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on Sunday, and pronounced dead soon after, authorities said.

Cambridge police superintendent Fred Cabral said officers had found Lewis’ body after being asked to perform wellness check by his wife, who was out of town.

A cause of death was not immediately available, but police said there were no suspicious circumstances.

For Mr Lane, Lewis’ death brought disappointment, but also the knowledge that he had done all he could.

“His death puts the pursuit of justice to an end,” Mr Lane told The Independent this week.

“Law enforcement doesn’t forget. We kept working at it for justice for the families.”