‘We took him to a hospital’: Army superiors knew Lewiston shooter was a risk before Maine attack

The hearing was held one day after the shooter’s family revealed that his brain had significant evidence of traumatic injuries

Army officials and law enforcement were both warned that Lewiston shooter Robert Card was suffering from deteriorating mental health in the months before the Army reservist shot and killed 18 people last year in the worst gun massacre in Maine’s history.

A special commission investigating the 25 October shootings held a public hearing on Thursday where they grilled the shooter’s former Army Reserve superiors, after questions were raised about whether they could have done more to prevent his actions.

The extensive questioning by the commission comes one day after the shooter’s family revealed that his brain had significant evidence of traumatic injuries, most likely from his time in the military.

Card, 40, was found dead of a self-inflicted gunshot wound after a two-day manhunt. He had shown signs of mental health decline before the massacre, but now, evidence shows that he suffered from traumatic brain injuries, according to an analysis by Boston University researchers.

Sgt Kelvin Mote from the Army Reserves, who was questioned at Thursday’s hearing, defended his efforts to contact the Sagadahoc County Sheriff’s Office regarding Card’s mental state and threatening behavior in the weeks before shootings.

When asked by the commission about how he felt when he found out the identity of the shooter, he appeared to fight back his emotions.

“It broke my heart,” he said. “We gave him options, we took him to a hospital. Nobody else did that.”

Sgt Mote, who is also a police officer, said he had removed someone’s weapon under Maine’s yellow flag law just eight days before the shooter came to his attention.

Sgt Mote testified that he believed he could have legally removed Card’s weapon, too. But he said he never mentioned that to sheriff’s deputies who had been asked by the Army to perform a welfare check. Under the law, the welfare check had to take place before any weapons could be seized.

Sgt Mote also recalled how the shooter reacted when law enforcement told him that the Reserve unit leaders had concerns about his mental state.

“I remember it clear as day, him saying, ‘Yeah, because they’re afraid I am going to do something,’” Sgt Mote said.

“And then he said the words that I put in my statement to Sagadahoc County: ‘I am capable.’ That was enough for me. At that moment, I decided he was going to the hospital, one way or another.”

Androscoggin Sheriffs Deputy Matthew Noyes told the commission on Thursday that he attempted to brief a Maine State Police detective about Card the night of the shooting, but claimed he was only given a couple of minutes to do so.

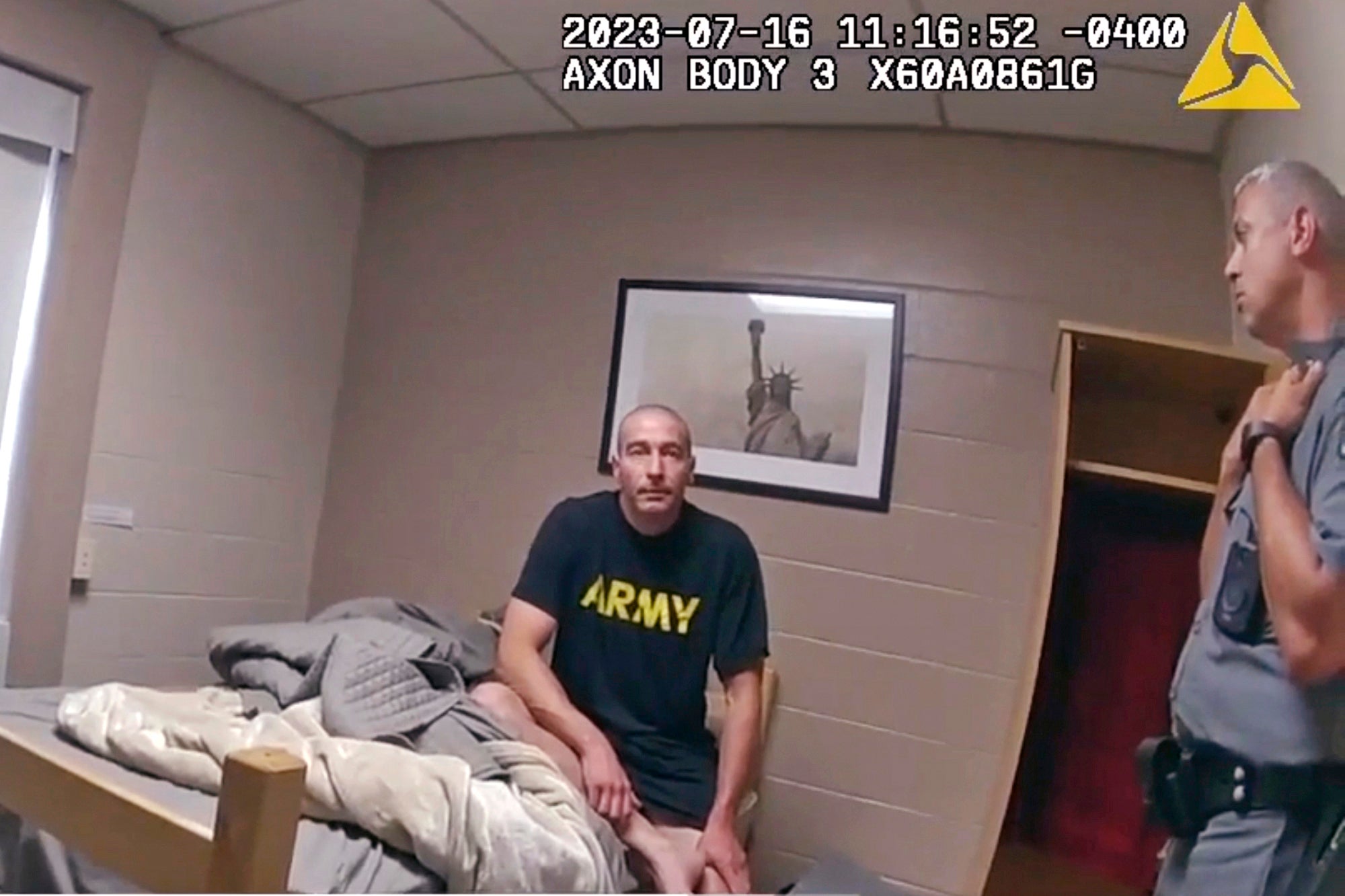

Some of the shooter’s relatives warned police that he was displaying paranoid behavior and they were concerned about his access to guns. Body camera video of police interviews with reservists before the shooter’s two-week hospitalization in upstate New York last summer also showed fellow reservists expressing worry and alarm about his behavior and weight loss.

Card was hospitalized in July after he shoved a fellow reservist and locked himself in a motel room during training. Later, in September, a fellow reservist told an Army superior he was concerned his Army colleague was going to “snap and do a mass shooting.”

Mr Noyes, who served with the shooter in the Army Reserves, said he was part of the team that escorted him to that psychiatric evaluation in New York a few months before the shootings.

“I felt good about what we did,” Mr Noyes said about getting Card to a hospital in July. “I thought he got the help he needed."

He told the commission that he believed it was law enforcement’s responsibility to remove the reservist’s weapons, because they had no authority to do it themselves.

Card’s Reserve unit commander Capt. Jeremy Reamer was also questioned about his efforts to follow-up with the Sagadahoc County Sheriff’s Office.

Card had been an instructor at an Army hand grenade training range, where it is believed he was exposed to repeated low-level blasts. It is unknown if that caused Card’s brain injury and what role brain injury played in Card’s decline in mental health in the months before he opened fire at a bowling alley and bar in Lewiston on 25 October.

The Maine Office of the Chief Medical Examiner’s office refused to comment on the results, which were released by Card’s family Wednesday.

The analysis showed degeneration in the nerve fibers that allow for communication between different areas of the brain, inflammation and small blood vessel injury, according to Dr. Ann McKee of Boston University’s Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) Center.

Dr McKee made no connection between the brain injury and the shooter’s violent actions.

“While I cannot say with certainty that these pathological findings underlie Mr. Card’s behavioral changes in the last 10 months of life, based on our previous work, brain injury likely played a role in his symptoms,” Dr McKee said in the statement.

The shooter’s family members also apologized for the attack in the statement, saying they are heartbroken for the victims, survivors and their loved ones.

“We are hurting for you and with you, and it is hard to put into words how badly we wish we could undo what happened,” they said in the statement. “While we cannot go back, we are releasing the findings of Robert’s brain study with the goal of supporting ongoing efforts to learn from this tragedy to ensure it never happens again.”

Commission chair Daniel Wathen said at a hearing with victims earlier this week that an interim report could be released by April 1.

Wathen said during the session with victims that the commission’s hearings have been critical to unraveling the case.

“This was a great tragedy for you folks, unbelievable,” Wathen said during Monday’s hearing. “But I think it has affected everybody in Maine and beyond.”

In previous hearings, law enforcement officials have defended the approach they took with Card in the months before the shootings. Members of the Sagadahoc County Sheriff’s Office testified that the state’s yellow flag law makes it difficult to remove guns from a potentially dangerous person.

Democrats in Maine are looking to make changes to the state’s gun laws in the wake of the shootings. Mills wants to change state law to allow law enforcement to go directly to a judge to seek a protective custody warrant to take a dangerous person into custody to remove weapons.

Other Democrats in Maine have proposed a 72-hour waiting period for most gun purchases. Gun control advocates held a rally for gun safety in Augusta earlier this week.

“Gun violence represents a significant public health emergency. It’s through a combination of meaningful gun safety reform and public health investment that we can best keep our communities safe," said Nacole Palmer, executive director of the Maine Gun Safety Coalition.