‘Poisoned’ in the womb, untreated conditions and orphaned: Nikolas Cruz had a horror start to life but did it matter at trial?

Parkland shooter Nikolas Cruz’s defence at his sentencing trial centred largely around his early life - from his apparent exposure to alcohol in the womb, the deaths of his adoptive parents and his behavioural and emotional problems. But did those details make a difference in the jury’s decision? Rachel Sharp reports

This story was originally published on 14 September. On 13 October, a jury sentenced Nikolas Cruz to life in prison.

It began before he was even born: Nikolas Cruz’s biological mother drank alcohol and abused drugs while he was still in the womb.

At the age of five, his adoptive father suddenly collapsed and died in front of him in the family home.

In his teenage years, he was allegedly bullied by his brother and sexually abused by a so-called “trusted peer”.

At 19, he became an orphan when his adoptive mother died from pneumonia.

And just three months later, he murdered 17 innocent students and staff in a shooting rampage at his former high school.

“Without any one of those problems, it may never have happened,” Abigail Marsh, professor in the Department of Psychology and the Interdisciplinary Neuroscience Program at Georgetown University, tells The Independent.

“For any given person there is a causal explanation, a link… and, on average, people who become mass shooters or are very violent have had these experiences or risk factors. There’s no one thing that you can say that is the reason but, together, a perfect storm of risk factors can give the means, motive and opportunity.”

These so-called risk factors have all come into focus in recent weeks as Cruz’s team of public defenders tries to convince a jury of his peers that his life should be spared.

Having pleaded guilty to 17 counts of murder and 17 counts of attempted murder over the Valentine’s Day 2018 mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, 12 jurors must now decide whether to sentence him to life in prison without the possibility of parole or to death.

In opening statements, lead public defender Melisa McNeill boldly admitted that his team has “no defence for this crime” and that Cruz is the “one person responsible for all the pain and suffering” caused by his actions that day in Parkland, Florida.

But, she vowed to walk them through his entire life to show them what “shaped” him into the school shooter and mass murderer he became.

Since the defence began presenting its case back on 22 August, jurors have heard testimony from dozens of witnesses comprising of relatives, neighbours, teachers, psychiatrists, psychologists and law enforcement officers who encountered Cruz at some point in his 19 years leading up to the massacre.

They spoke about Cruz’s troubled start in life, the challenges in his upbringing, and the behavioural and psychological difficulties he presented from a very early age – which many say were not properly addressed.

“He’s a damaged human being and that’s why these things happened,” his attorney Melisa McNeill said in the opening statement.

“We must understand the person behind the crime... in telling you about his life we will give you reasons for a life.”

Nature

Cruz was born on 24 September 1998 to Brenda Woodard, an alcoholic and drug addict who was living on the streets and working as a prostitute. The identity of his father remains unknown.

According to testimony from her daughter Danielle Woodard, Cruz was “polluted” in the womb as their biological mother continued to abuse alcohol and drugs and smoke during her pregnancy.

The defence has said that this caused Cruz to suffer from fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD). FASD are conditions caused by an individual being exposed to alcohol in the womb before birth and they can often lead to both physical problems and behavioural and learning problems, such as learning disabilities, hyperactive behaviour, and poor reasoning and judgment skills.

Ms McNeill said that Cruz’s “brain is broken” from this prenatal exposure to alcohol.

“His prenatal vitamins consisted of... Bum wine, crack cocaine and cigarettes. Because of that his brain is irretrievably broken,” she said.

Dr Kenneth Jones, who is regarded as one of the nation’s top FASD experts, testified that he has “never seen” a woman abuse alcohol while pregnant as much as Cruz’s biological mother.

“I don’t think I have ever seen — I know I have never seen — so much alcohol consumed by a pregnant woman,” he said, adding that he has studied more than 1,000 people with prenatal alcohol exposure in his 50-year career.

While his birth mother’s substance abuse may have had a lasting impact, his relationship with her ended as soon as he was born. Woodard had placed him up for adoption and his adoptive mother Lynda Cruz was in the delivery room at his birth. Lynda took Cruz home to live with her and her husband Roger.

When Cruz was less than a year old, Woodard became pregnant again. When she gave birth to Zachary, Lynda and Roger brought him home as their second son and Cruz’s younger brother.

Even as a baby and toddler, experts began to notice that Cruz was intellectually and physically behind other children.

Anne Fischer, the director of the pre-school Young Minds Learning Center which Cruz attended from the age of one, testified that he had social and communication difficulties and bit other children.

“She told me later in time, his mother was an addict,” Ms Fischer said Lynda told her of Woodard.

When Cruz was around four or five, Cruz would “pounce” on other children if they got too close to him and he displayed “animal fantasy behaviours”, according to testimony from special education teacher Susan Hendler Luber.

Neighbours and friends also noticed that he was slower than other children of the same age, had aggressive tantrums and struggled to mix with other children. Cruz underwent evaluation and was found to be socially and emotionally developmentally delayed.

Over the course of his childhood, Cruz would be diagnosed with a string of other conditions and disorders including ADHD, autism, depression and emotional behavioural disability, official records show.

Nurture

In tandem with these biological factors, Cruz also faced challenges in his upbringing including the untimely deaths of his two adoptive parents.

The first few years of his life were much like that of any content, middle class family living in a suburb of Florida. They were comfortably well-off, living in a sprawling house with a swimming pool, jacuzzi and a basketball court.

Then, one day in August 2004, five-year-old Cruz was in the den of his family home with Zachary and Roger, while his mother was in the kitchen.

Suddenly, Nikolas ran past Lynda crying, Lynda’s friend Finai Browd testified. When Lynda asked her son if his father had yelled at him, Cruz allegedly gave a harrowing response.

“As clear as sunshine he said, ‘No, Daddy is dead,’” Ms Browd told the court.

Roger had collapsed onto the couch dead from a heart attack. He was 67. Lynda was then left to raise the two boys alone.

While many witnesses have testified that she loved her sons and did the best she could for them, it’s clear that she struggled to raise the two boys, who both had behavioural difficulties.

Neighbours and behavioural experts testified that Cruz and Zachary destroyed things in the family home and – in their teenage years – Lynda regularly called the police because of their behaviour.

In total, the Broward Sheriff’s Office had 43 contacts with the Cruz family prior to the Parkland massacre, 21 of which involved Cruz alone or both him and his brother, according to official records.

As Cruz got older, Lynda began to fear her eldest son, according to former neighbour Paul Gold.

“She told me she was scared of him,” he testified. “She told me not to believe the nice appearance he had and angelic ways and that he would turn and do bad things. And she was a little afraid of him at some times.”

Though Cruz was the older of the two, multiple witnesses have also testified that Zachary bullied his brother.

In one 2013 incident when Cruz was eating cereal, Zachary climbed onto the countertop and stepped on the food, recalled Tiffany Forrest, Cruz’s former youth case manager.

Cruz was also allegedly sexually abused by an unnamed peer. The details of this incident are yet to surface in courtroom testimony.

His behaviour worsened as he got older. One time, when his family dog died after eating a toad, Cruz allegedly went on a “killing spree” of all the toads in the neighbourhood. At one point, he was also accused of “inappropriately touching” a young girl.

When he was 14, his school therapist learned that he was having dreams about killing people and being covered in blood.

In what can now be seen as a foreboding letter, mental health professionals described him as “aggressive” and “paranoid” and said that he had “a preoccupation with guns”.

In November 2017, just three months before the school shooting, Lynda died from pneumonia. Cruz and Zachary were left parentless.

Only five people, including her two sons, attended her funeral. Cruz was “very upset” that so few people showed up, according to their former neighbour Paul Gold.

Following her death, Cruz and Zachary initially moved in with former neighbour Rocxanne Deschamps but Cruz lasted there less than a month. The police had been called to the home over an alleged fight with Ms Deschamps’ son and Cruz had to move out.

“Every risk factor” was there to indicate that Cruz could go on to carry out a major act of violence, says Ms Marsh.

“There’s one biological parent with a significant challenge herself so there’s a familial risk factor from the get go, the perinatal risk from the FASD which disrupted his development, early violent behaviour in childhood, a mother who was a little permissive and not good at enforcing consequences on disruptive behaviour... In general violence in young adults is overwhelmingly men with a history of significant disruptive and violent behaviour in childhood,” she said.

Nature v nurture

Yet, questions emerge around whether these biological and environmental risk factors can be blamed for Cruz’s actions on Valentine’s Day 2018 -- particularly when taking a closer look at his siblings.

Danielle Woodard shares the same biological mother but, unlike Cruz and Zachary who were adopted, she was raised on and off by their mother and spent time in foster care.

The potential impact of her upbringing was visible when she entered the courtroom. Flanked by guards, she walked up to the witness stand dressed in prison garb and handcuffs.

Having been in and out of jail her whole life, she is currently facing life in prison over the 2020 carjacking of a 72-year-old woman.

Under cross-examination, prosecutors compared her upbringing to Cruz’s and asked her how she would have felt if someone had adopted her and taken her to live in a home like the one that her brother grew up in.

“I would have thought that would have been a great thing,” she told the court.

Meanwhile, Zachary’s start in life was near identical to that of Cruz. The 22-year-old, who is expected to testify in his brother’s defence, shares the same biological mother. He was also adopted by Lynda and Roger Cruz from birth, growing up in the same home and experiencing the same parental loss as Cruz.

Courtroom testimony revealed that Zachary also had behavioural issues and was in trouble for allegedly stealing. In the aftermath of the massacre, Zachary was given six months probation for trespassing at Marjory Stoneman – the site where his brother carried out his murderous rampage.

He visited the site of the massacre at least three times despite being warned to stay away, according to an affidavit.

Zachary, who turned 18 one week after the massacre, was said to have become fascinated with “how popular [Nikolas’] name is now” and questioned whether the fame would help to attract female attention.

While Zachary might not have an unblemished record, it’s a far cry from his brother who carried out one of the deadliest mass shootings in American history – raising key questions about the role of nature versus nurture in Cruz’s decisions that day.

In a biological sense, Ms Marsh says that having different fathers can make a “big difference” to psychological traits such as violence and aggression. In an environmental sense, there are “a lot of idiosyncrasies in life” that make a big difference to individuals in different ways.

“How a lot of kids turn out is not down to huge factors such as substance abuse or family income but a huge amount of life outcomes are due to idiosyncrasies,” she explains.

“For example you hear of people who had one particular teacher who introduced them to one particular hobby that they loved that then changed the trajectory of their life. Life is full of those things… so kids can have the same biological mother and be adopted by the same parents and so they have a bunch of things that are similar but they also have various other pieces of life experiences.”

She adds: “There’s a perception that the big picture factors play a much more significant role in a predictable way when there’s so much of life linked to idiosyncrasies.”

In this sense, while jurors are learning about the major risk factors Cruz had, Ms Marsh explains that sometimes it is the smaller experiences that can have the biggest impact.

Then, there is often a “major life event” which is the final tipping point to the violent act.

“For some people it can be losing their job and it causes a major cascade of emotions and causes them to erupt,” she says.

In Cruz’s case, it’s possible this “major life event” could have been the death of his adoptive mother.

However, Ms Marsh says that to get to that stage it requires a “really unfortunate, volatile combination of factors” already.

“We always think of nature and nurture working together to come to outcomes, not one or the other,” she says.

Intervention

There may be no doubt that Cruz had a troubled start in life, but others go through similar experiences and conditions and don’t carry out mass shootings.

Back when Cruz’s sentencing trial began back in July, the non-profit FASD United released a statement to that point, saying that the mass shooter “does not represent the FASD community”.

While people with FASD are “more vulnerable to negative environmental influences, which can lead to failed social outcomes”, with care and support “these individuals can and do lead productive lives”, it said.

Cruz had been in and out of psychiatrist, therapist and psychologists’ offices all throughout his childhood.

While he began receiving services from the age of three and was diagnosed with several conditions, the extent and appropriateness of the intervention he received remains unclear. The court has heard somewhat contradictory accounts about whether he got the support he needed, both in the home and from education and behavioural health services.

Several witnesses have testified that Lynda initially struggled to admit that her son needed help. She did come to terms with it, had Cruz assessed and was later described as “very involved” in his care. But, she wasn’t consistent in getting him treatment.

Psychologist Frederick Kravitz said that Lynda brought Cruz to him when he was 8 years old saying that he suffered from anxiety and temper issues.

The psychologist recommended Cruz should attend weekly sessions, but he testified that Lynda only brought him in 15 times over a 13-month period.

Despite his difficulties, Cruz also spent a significant amount of time in general education schools and moved around a lot of schools. When he was in eighth grade at mainstream middle school West Glades, he was found drawing pictures of shooting victims and naked people and found “any excuse to bring up guns”, according to a functional behavioural assessment shown in court.

In one class in September 2013, he “became fixated on death and assassination of Abraham Lincoln” asking what it sounded like when he was shot and if people “ate” the bodies of people killed in the Civil War.

One teacher kept detailed notes of his behaviour and warned that he needed to go to “a facility that is more prepared and has the proper setting to deal with this type of child”.

In one assessment, she warned: “I strongly feel Nikolas is a danger to the students and faculty at this school. He does not understand the difference between his violent feelings and reality.”

Despite her concerns, the school simply made a plan to help deal with Cruz’s behaviour that consisted of more incentives and verbal compliments.

He was finally moved to Cross Creek – a school that focuses on student’s special education needs – in early 2014 but ended up back in a mainstream school again when he was sent to Marjory Stoneman in January 2016. His attorneys say that he “never should have gone” there. He left in February 2017.

He returned one year later with an AR-15.

Does it matter?

While psychologists, psychiatrists and other experts can point to factors that may have contributed to Cruz carrying out the atrocity that day, the answer to “why?” will hardly bring any comfort to the families of his 17 murder victims.

It also remains to be seen whether it will have any impact on the jurors deciding his fate.

Duncan Levin, a prominent criminal defence attorney at Levin & Associates and former assistant district attorney in the Manhattan DA’s office, says the defence is doing the only thing it can in a case like this: try to “humanise” Cruz in the eyes of the jury.

“It’s very important for the defence to try to humanise him in every way possible and to bring evidence before the jury so that they know more about the person that they would be sentencing to death,” he tells The Independent.

Mr Levin explains that the more the jurors get to know the defendant, the more difficult it can be for them to send him to death row.

“It is a very heavy thing for a jury to do to sentence someone to death – these are lay people who are being asked to vote to kill somebody,” he says. “So the defence is trying to personalise him as much as possible to make this a more difficult, personal decision for the jury.”

It’s a strategy that aims to counter the harrowing case presented by the prosecutors seeking the death penalty.

For three weeks, jurors heard graphic details of how Cruz plotted and carried out his attack at the high school. They were shown how he stalked the hallways of the freshman building, killing as many students and staff members as he could.

They watched surveillance footage of him in the aftermath, calmly going to a nearby Subway for a drink and then onto a McDonald’s where he sat down and spoke with a student whose sibling he had shot just minutes earlier.

Grieving family members of each of his 17 victims broke down in tears on the witness stand as they spoke about their loved ones and the toll his actions have taken on the people they left behind.

Jurors also toured the school site and saw the blood-stained corridors and classrooms just as they were left in the aftermath of the massacre.

Following the prosecution’s case, Mr Levin says that trying to “personalise” Cruz is the defence’s only hope of saving his life.

“There’s very little to do at this point other than show mitigating factors,” says Mr Levin of the defence. “That’s the only opportunity they have to try to undo some of [the prosecution’s case] and personalise him.”

Calling dozens of witnesses who knew Cruz and presenting hours of courtroom testimony about his life is all part of an attempt to build this “cumulative” effect.

However, given the nature of Cruz’s crime and the notoriety around the case, Mr Levin feels that the defence is still fighting an “uphill battle”.

“This is about as difficult a case as as any defence lawyer can get. The lawyers in this case have a very unenviable task as they’re representing perhaps one of the most hated people in the world,” he says.

“Now they’re in the penalty phase, he’s not presumed innocent anymore so that has changed the tenor of proceedings in a very dramatic way. To say they have an uphill battle is an understatement. They’re climbing an extremely steep mountain here and its unlikely that – given the facts of the case – it’s going to make a huge difference… it’s like throwing a pebble into the ocean.”

He adds: “The problem is that the crime he committed is so hideous that it’s really not going to matter much to people that he had a difficult upbringing.”

Learning about all of Cruz’s risk factors for violence may evoke some empathy from the jury, says Ms Marsh.

But, she says it could also show jurors that Cruz is “less able to be rehabilitated” and “these motivations could then cancel each other out”.

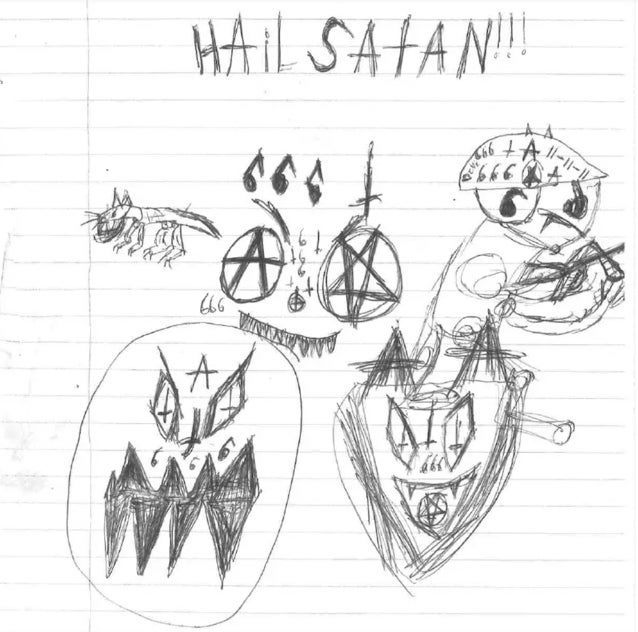

In the more than four years between the massacre and the trial starting, there appears to be no sign of his disturbing behaviours abating. A trove of chilling jailhouse drawings and notes released by the Broward Sheriff’s Office last month offered a glimpse into his current state of mind behind bars.

Among the incoherent scrawlings is Satanic imagery, drawings of guns and ammunition and notes saying that he wants to “go to death row” and then be “buried with a woman who had a s***ty life like me”.

“I do not want to be bothered by anyone or anything, I can’t wait to die. Blood, blood. I only wanna see blood,” he wrote in one note.

In another harrowing drawing, Cruz appeared to have recreated the school shooting at Marjory Stoneman, with students sat at desks in a classroom and a gunman.

The 23-year-old also wrote “666” in his own blood on the walls of his prison cell just two months before the trial began. The discovery of the notes and blood-stained wall prompted prison guards to place him on suicide watch back in May.

In an unusual twist, Cruz has also spent his time in jail speaking with the mother of a student killed in another school shooting.

Scarlett Lewis, mother of six-year-old Jesse Lewis who was murdered in the 2012 Sandy Hook massacre, has visited Cruz in prison via video and had phone calls with him.

Cruz’s attorney said that “her and Nik are trying to find a way to prevent this from ever happening again”.

Understanding the potential part that Cruz’s psychological and behavioural conditions and upbringing played in him murdering 17 people has greater significance than the outcome in court, says Ms Marsh.

It’s about spotting warning signs in future and preventing other children from growing up to become the next mass shooters.

“People don’t want to understand people like Cruz for obvious reasons but trying to understand the process that led him to act that way is different to sympathising with him or condoning what he did,” she says.

“By understanding what happened we can connect other kids to what interventions they need rather than pretend things are fine and let awful things like this happen again.”