A DNA report casts doubt on the entire JonBenét Ramsey case. This detective says it could help solve her murder

A Colorado sheriff watched his best friend, Lou Smit, dedicate his life to solving the 1996 murder of six-year-old pageant queen JonBenét Ramsey — then helped continue the investigative cause after Smit’s death. Now John Wesley Anderson has written a new book including an unredacted DNA report — and tells Sheila Flynn the results could upend the decades-long investigation

Colorado sheriff John Wesley Anderson was celebrating his March 1997 wedding in Las Vegas when his best man, investigator Lou Smit, brought up the killing of JonBenét Ramsey – which had stunned the world 10 weeks earlier. Smit, not only the El Paso County sheriff’s best friend but also his recently-retired captain of detectives, was considering a special investigator position with the Boulder district attorney to assist in the probe of the six-year-old beauty queen’s death — a job he ultimately accepted.

Mr Anderson and his new bride flew from Vegas to their honeymoon; Smit returned to Colorado to join investigators in Boulder. Little did both men know that the case would become a driving force in Smit’s life. He resigned in disgust within two years, claiming Boulder authorities were ignoring key evidence, then sought to prove the Ramsey family’s innocence for the rest of his life. A seasoned detective with more than 200 murder cases under his belt, Smit was outspoken and convinced JonBenét’s slaying would be solved through DNA.

Now, more than a quarter century after that Vegas conversation and 13 years after Smit’s death, Mr Anderson has written a new book about his friend’s quest to solve JonBenét’s murder. And it includes an unredacted lab report from just weeks after the murder detailing DNA markers that could have “excluded” the Ramseys and other members of their inner circle.

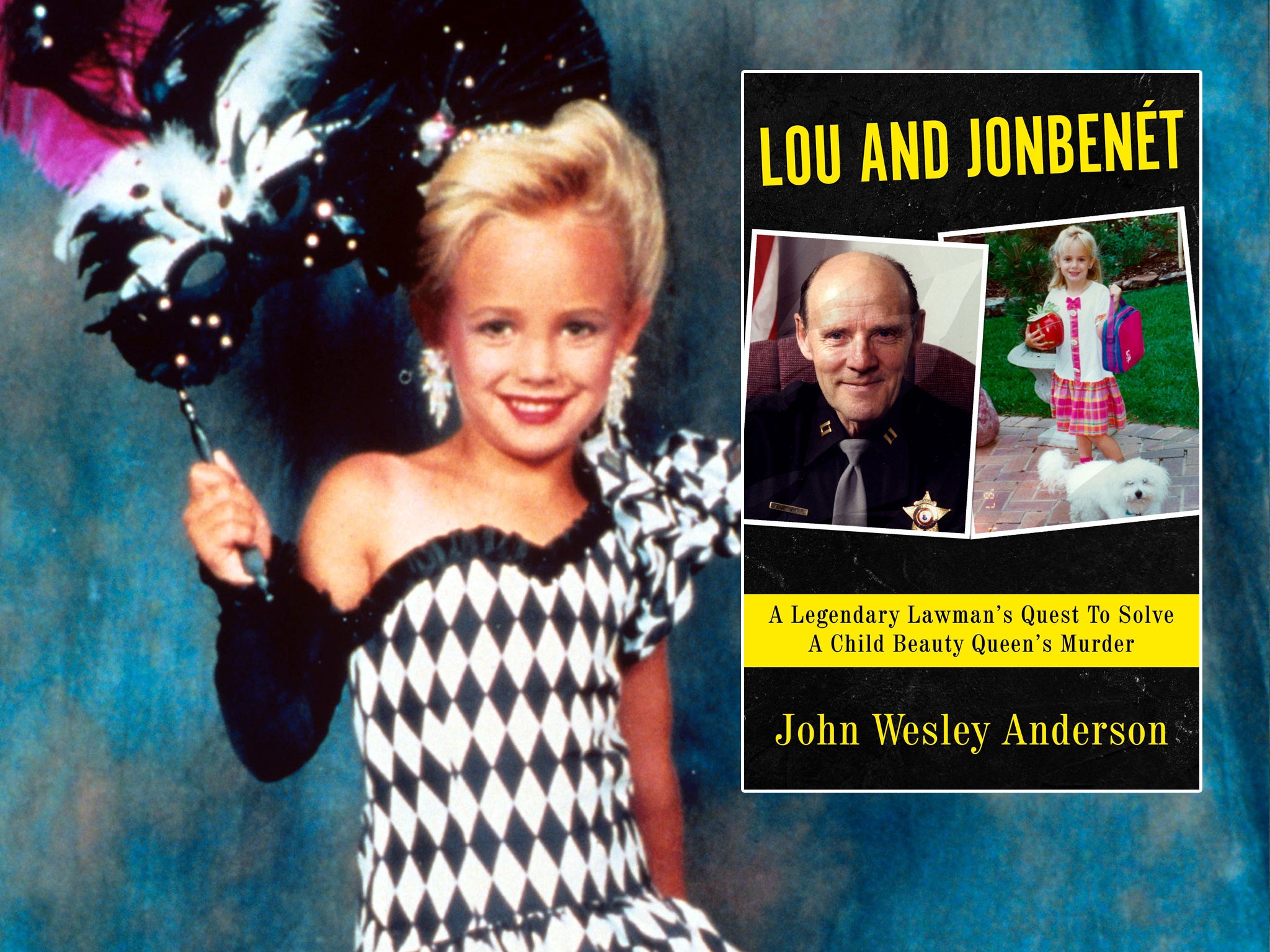

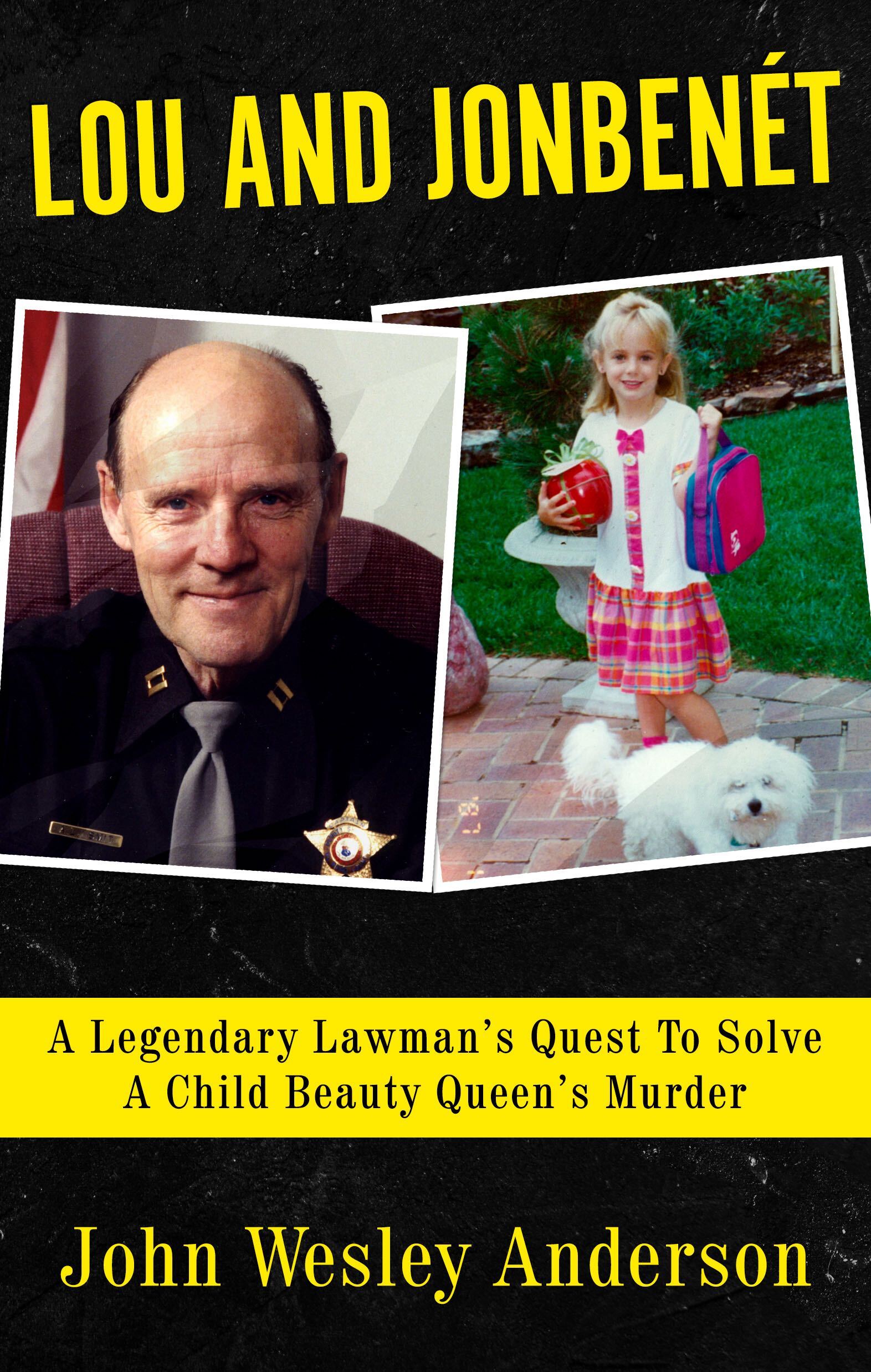

The retired sheriff-turned-author – to his surprise – chokes up when he talks to about his late friend and the book. Its cover features a photo of Smit alongside a kindergarten picture of the tiny girl whose killer he vowed to expose.

“I think what the cover really does is to really capture that these two people, who never met ... this is a story about two important people,” Mr Anderson tells The Independent, just over two weeks before the publication of Lou and JonBenét: A Legendary Lawman’s Quest to Solve a Child Beauty Queen’s Murder.

“I’m proud of the book because I think it’ll tell the story, the true story, the inside story that’s never been told, of Lou and JonBenét.”

Mr Anderson believes that the “case is still solvable,” adding that the Smit-inspired team worries about “that violent of an evil killer out there.”

“We can’t sleep until that person has been identified and apprehended and this case is solved,” he says. “So it’s not just justice for JonBenét ... it’s public safety. This is one of the worst, most evil people imaginable.”

Following Smit’s death in 2010, his family, friends and fellow former detectives continued his investigative work, poring over his case files, narrowing down a list of suspects and continuing to surveil individuals and attempt to obtain their DNA. Mr Anderson, part of the team, decided to write the book on 26 December 2020 — the same day fellow investigator Dave Spencer died and, strangely, the 24th anniversary of JonBenét’s murder.

“It made me realise that a lot of the burden in documenting the case was falling upon my shoulders ... and I thought there [was] a chance that we wouldn’t finish this work in my lifetime,” he tells The Independent. “And I wanted to make sure that we had left the documentation as complete as possible for the next generation, because Lou’s grandchildren had started being a part of our team.”

“And I thought, I really owe them a firsthand account to document as best as I can what this investigation’s about, the key pieces of critical evidence in solving the case, the DNA ... I’m kind of in a unique position because they’ve gone now,” he says of his friends Smit and Spencer. “I’m the only one who ... had a front row seat, who had the first-person account” after years of witnessing Smit’s investigation and advocacy, in addition to joining the team himself.

A major part of that documentation, Mr Anderson says, was highlighting an unredacted copy of a 1997 lab report from the Colorado Bureau of Investigation which found genetic markers under JonBenét’s fingernails and on her clothing. Parts of the report had been circulated previously online; Mr Anderson says the key unredacted portion included in his book, however, was not publicly available in the past.

It compares the genetic markers with “standards” samples that had been collected from the Ramsey immediate family, a few extended relatives and members of their close inner circle.

“If the minor components from exhibits #7, 14L and 14M were contributed by a single individual, then John Andrew Ramsey, Melinda Ramsey, John B. Ramsey, Patricia Ramsey, Burke Ramsey, Jeff Ramsey, John Fernie, Priscilla White and Mervin Pugh would be excluded as a source of the DNA analyzed on those exhibits,” states copy of the unredacted document, which came into Smit’s possession through his work as a DA investigator.

Boulder authorities eventually, in 2008, said the Ramseys had been cleared through developments in touch DNA, sending a letter of apology to John Ramsey; Patsy had died two years earlier. But the report included in Mr Anderson’s book raises questions about whether the Ramseys could have been cleared far earlier.

Public perception and suspicion of the family continued and persists to this day.

Mr Anderson says that “some people I’m sure will criticise me for [releasing the report], being in law enforcement, since this is an open investigation.

“We really didn’t do that easily,” he tells The Independent. “We made that decision very consciously, and I’m glad we did, because I think it was critical that the truth comes out.”

The book, he says, “was intended to accomplish two things of equal importance”.

“The first objective was to establish, beyond any reasonable doubt, that no one in the Ramsey family was involved in the death of JonBenét, and that was critical, because the family had been the focus of speculation” from all sides, he says, adding that the “cloud [of suspicion] has tainted and really just destroyed that family.”

The second objective, he says, was “to communicate the fact that this case, even though it’s 26 years old, is still solvable. DNA evidence is lock solid, we have at least 14 genetic markers that will identify this killer [and it] eliminates huge populations. It’s definitely male ... and there’s some strong indication that the genetic material is that of a Caucasian male.”

JonBenét was reported missing from her Boulder home on the day after Christmas in 1996. Hours after the initial police response, the six-year-old’s body was found in the basement by her father, John. Less than three months later, Smit came out of retirement to help the Boulder district attorney’s office investigate the murder which had become a national obsession thanks to factors that included the family’s wealth and social standing — but particularly the distinctive pageant shots of the diminutive beauty queen.

“He went in with the assumption that everyone else had at the time — that this is going to be a matter of just deciding or finding out which family member” had committed the crime, Mr Anderson says of his friend.

He continues: “What was being reported was, there’s no forced entry; there’s no footprints in the snow. And so, from a law enforcement background, you’re thinking, ‘Oh, this ought to be fairly straightforward.’ And I know Lou thought it would not be nearly as complex as it was.

“So the next time we talked — I’d been back from our honeymoon about a week, I guess — I asked him, ‘How’s it going in Boulder?’ He said, ‘Johnny, there’s something wrong here.’”

Smit resigned 18 months later, writing on 20 September 1998 that Boulder police were choosing “to follow a theory and let their theory direct them rather than allowing the evidence to direct them”.

“The case tells me there is substantial, credible evidence of a intruder and lack of evidence that the parents are involved,” he wrote. He would later publicly outline many of his gripes with the investigation, including his insistence that marks on JonBenét’s body indicated that a stun gun had been used to subdue the child.

“It was a vicious attack and a horrible murder, and that killer went into that house with a kidnap kit,” says Mr Anderson, who worked in law enforcement for three decades. “He brought duct tape, he brought parachute cords, he brought a stun gun to immobilize the victim. So this was very calculated. It was a very methodically executed kidnap attempt that went wrong and ended up in murder.”

The author, like Smit, believes evidence has been cast aside for decades.

“It was really confusing at first, how anybody can ignore the physical evidence, as a matter of inexperience or supervision, or it really evolved to the point of more frustration, aggravation, and a realisation you're dealing with arrogance,” Mr Anderson says.

The assumption of the Ramseys’ guilt, however, filtered down to the public consciousness and has persisted since 1996. In 2017, Burke Ramsey — who was at nine the time of his little sister’s death — filed a $750m defamation lawsuit against CBS for its docuseries focused on the theory that he’d been responsible for the murder. The suit was settled and dismissed after two years.

JonBenét’s mother, Patsy, died in 2006, and her father, John, has spent years pleading for further DNA investigation. In November, Boulder police and the district attorney announced that they would be partnering with the Colorado Cold Case Review Team to pursue more answers.

The following month, the Boulder Police Department announced that five officers had been disciplined after an internal audit discovered that some cases between 2019 and 2022 “had not been investigated or investigated fully”. Among them was Commander Thomas Trujillo, who had been an original detective on the JonBenét Ramsey case and had been present for the initial interviews of her parents. (The Ramsey case was not among the cases found to be improperly investigated in recent years.)

The department announced in its November release that Mr Trujillo had been transferred from head of the Investigations Unit to head of night patrol and been given a three-day suspension without pay. All mention of his time as head of the Investigations Unit has been scrubbed from his bio on the police department site.

The Police Oversight Panel had recommended all five officers be terminated, according to the BPD release.

Mr Anderson says, before the commander’s involuntary transfer, he had not only presented the lawman and other members of BPD with his team’s findings but had also been repeatedly rebuffed or ignored.

In response to a detailed list of questions from The Independent regarding the 1997 DNA report, the status of the JonBenét probe and who heads up Boulder’s Investigations Unit now, a BPD spokeswoman said only that the department recognized that “many articles and books have been written about this tragic homicide.

“We have not read this newest book which, apparently, contains allegations from the late 1990s,” she continued. “ At present, this active investigation continues to receive assistance from federal, state, and local partners. Boulder Police is working with multiple agencies, including the FBI, the District Attorney’s Office, Colorado’s Department of Public Safety, Colorado’s Bureau of Investigation (CBI), and several private DNA laboratories across the country.”

Mr Anderson and the late Smit’s team, meanwhile, have been spending their own time and money conducting their own investigations.

“What our team has done, since Lou passed in 2010, has been reprioritizing and looking for those persons of interest that might have had a connection to the Ramseys, might have had a motive to do something to them, might have had some financial incentive or whatever,” Mr Anderson says. “And then, sometimes, with their consent, sometimes surreptitiously, we’ve tried to focus on those individuals that would most likely have a connection and privately collect and test their DNA against the genetic markers that were left at the scene and later recovered from some of the other clothing.”

The team has eliminated more than a dozen people of interest from its original list, he says, and continues to work its way through.

“Each of those people earned their way onto our top 20 list,” he tells The Independent. “It wasn’t just throwing a dart.”

He and his fellow detectives are bolstered by advancements in DNA technology and developments such as forensic genealogy, he adds.

“These cold cases all across the country — to include two that were solved in Colorado Springs — they’re being solved by people, detectives, crime lab people looking at the same evidence that’s been there for 20, 25, 30 years, and just using new technology,” he says.

“Once you get past ‘the Ramseys did it,’ there’s a whole boatload of people that have never been investigated, or I should say, never been competently investigated, with their DNA being used to exclude them as potential suspects,” he tells The Independent.

“There’s always the possibility, after 26 years, the person’s been incarcerated, they’ve died or whatever,” he says. “But there’s no better time to solve this than there is now.”