Guns, deadbolts and a mass student exodus: Terror grips Idaho college town after quadruple murder

Parents are ordering deadbolts, teens are asking for guns and the streets are empty in Moscow. There is a killer - or killers - on the loose, more than three weeks after four college students were murdered in their beds. Locals tell Sheila Flynn how fear is deepening as time goes by without any arrests and with little information from police

Moscow Lock Shop can’t keep up with the demand for deadbolts.

The calls started coming in just hours after police discovered four University of Idaho students fatally stabbed on 13 November. Then the phone started ringing even more; by 17 November, the number of calls had reached 50 in a day.

“If you imagine that there’s two of us working, and then we’re going out and actually doing calls, and there’s 50 phone calls in one day ... we’re not getting them all done,” locksmith Casper Combs, 28, tells The Independent, pointing out that it takes about an hour to install each deadbolt.

The Lock Shop has a waiting list “past Thanksgiving, that’s for sure,” he says. Most of the calls come from landlords and scared parents of students at UI, which is less than a mile away – “typically moms who are worried about their kids.”

“Little town Moscow doesn't get a lot of drama, thank God,” says Mr Combs. “We're lucky enough to live in a town where this type of thing is kind of so outlandish ... everybody is just freaked out, and that's all that they're talking about.”

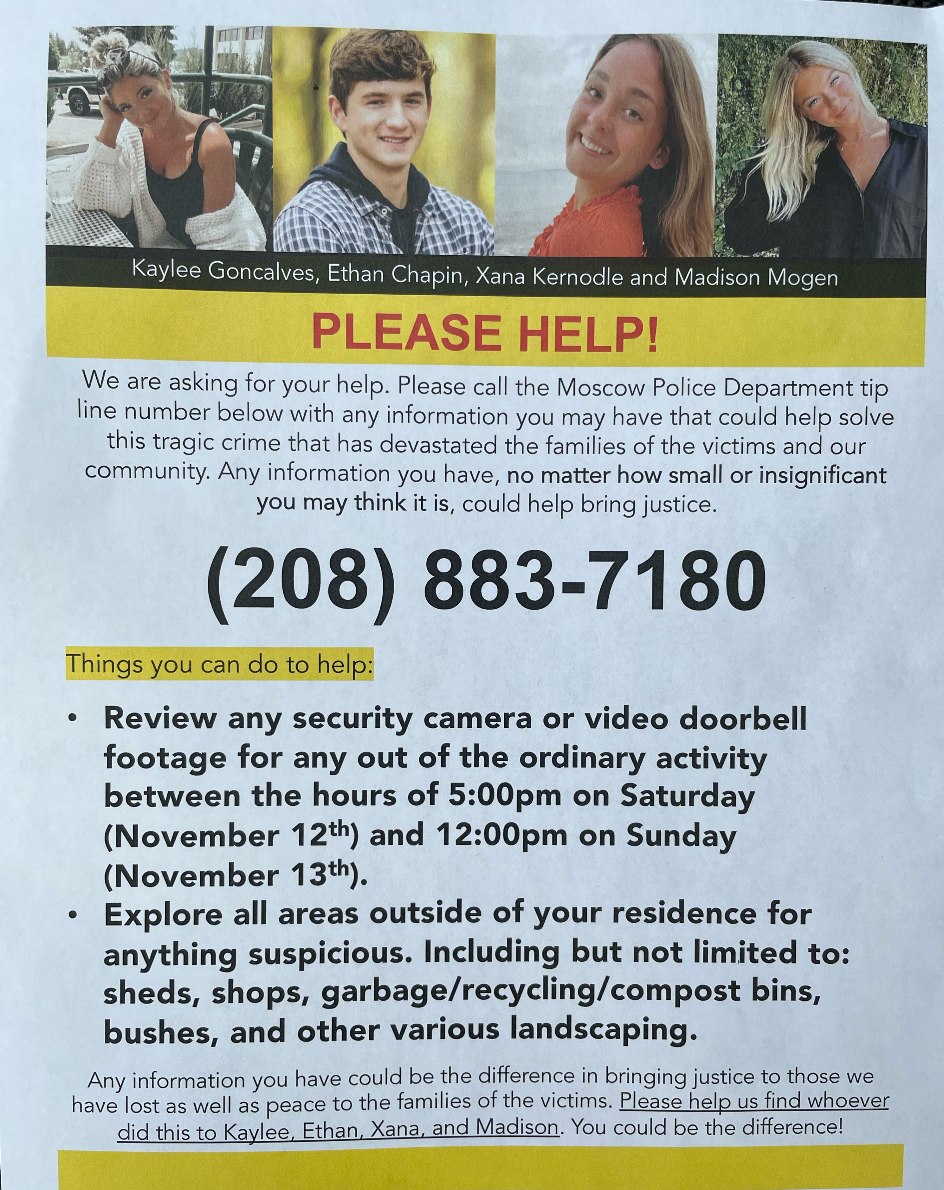

With a population around 25,000 on the border with Washington state, Moscow has been reeling since a 911 call around noon on 13 November led police to the gruesome discovery of Ethan Chapin, 20, Kaylee Goncalves, 21, Xana Kernodle, 20, and Madison Mogen, 21. They were found on the second and third floors of a house the women shared on King Road with two other roommates who police said slept through the attack.

Authorities have been sparing with other details ever since, however, and have been particularly vague about whether ot not people in Moscow should be scared. Initially, cops said the murders were targeted and there was no threat to the community; on 16 November, however, they held a conference to say they couldn’t rule out a continued threat and urged locals to be vigilant.

The following day was when the calls to Lock Shop reached their peak.

“I have a set of friends who haven’t left their house since last Sunday ... this is the extent that people are freaking out,” the locksmith says.

The last murder in Moscow was seven years ago, and the town has only seen a handful of others in living memory. In an odd connection, the building housing The Lock Shop was also the scene of what had been the town’s most famous murder, up until last week. In December 1969, 18-year-old waitress Janice Foiles was bludgeoned to death at what was then the Tip Top Cafe.

That case also remains unsolved - which doesn’t necessarily bode well for local cops’ track record.

Residents this week are getting increasingly frustrated with the perceived lack of progress - and clear lack of information - about the investigation into the four students’ murders. The uncertainty is fuelling fear, which in turn fuels the very rumours that authorities and victims’ families are trying to quash.

“The fact that they came out and told us this was a targeted event, and then to backpedal that and say, ‘Well, you know, stay vigilant and stay aware,’ and then have [Moscow Police Chief James] Fry tell everybody that, ‘Well, you know, we just dont know ...’ From one message into another, it just makes everybody so uneasy,” says Matt Johnson, 42, who owns Moscow Tattoo Company.

He grew up here and has been proactive in trying to ensure safety; the weekend after the killings, Mr Johnson posted a message on the shop’s Facebook page offering to not only walk anyone, not just customers, to their cars but to also “clear your house before you lock yourself in.”

“I get [that] there’s a certain amount of information that the local police department has to hold out on to not jeopardize their investigation, but I think it’s that uncertainty of not being able to get an answer if this community is safe or not, you know, that is leaving most people scared,” he says.

The community itself has shrunk since the murders; UI senior Dylan Bartels couldn’t believe how quickly his campus emptied out when he went to class two days after the murders.

“Normally, I have to drive around five minutes trying to find a parking spot; I pulled in and one of the closest spots is open,” he tells The Independent. “I mean, literally, the student population going to class declined by 50 per cent. Overnight.”

A 6’2”, 240-pound former member of the UI football team, the Colorado native says he’s one of the few staying on campus - and he, too, is nervous.

“I’m here til Christmas; I don’t have the option to go home,” he says. “And for me, it’s concerning ... we have no idea if this was a student or was not. And it puts me on edge, the fact that I need to go sit in a classroom and I could be sitting next to someone that unstable. Whoever that is that did this, you know, that’s a very unstable person who even had the reasoning to be able to take this on.”

Mr Bartels, 22, says he’s not a big partier but would sometimes “go down to one of the local bars and grab a couple of drinks on a Friday night.

“I haven’t done that since this happened, and I won’t,” he says.

There are those, of course, who brush off the new danger – a recent UI grad who boasts she hails from a rough part of California and knows how to take care of herself; a store worker who says they’d never walk alone at night anyway.

Then there are the people who literally saw the danger brought to their doorsteps.

Ty Styhl’s 18-year-old daughter lives next door to the crime scene, he tells The Independent, and she’s “pretty freaked out.”

“She asked me for a gun,” says Styhl, 38, though he didn’t agree; instead, his daughter is having friends stay at the home with her and carefully locking her doors. Many in Moscow never bothered to lock up before.

Now, however, it’s a different story. People aren’t sure just how many students are even coming back.

“I think that a lot of kids right now are just like, I don’t even want to be around an environment this [tense], and I don’t blame them,” says Mr Bartels. “I’ve heard from a lot of people they’re coming back for like a one-day stint to grab their cars or to get their stuff or whatever. As far as people coming back next semester, I think that’s really going to come down to how much information is going to come out.”

As Mr Bartels speaks, Mr Johnson is working on an extensive touch-up on the senior’s left arm; the prolonged absence of students is already worrying the tattoo artist.

“There’s a huge freaking dark cloud over this place,” he says of Moscow. “The uncertainty for us, as business owners, not knowing if the students are going to come back ... in my line of business, you know, we rely on them. They are a part of our community. And we can’t survive without them here. So if they’re not here, we’re stuck.”

Mr Johnson also tattoos a lot of cops and has friends on the force; he knows the long hours they’ve been working and has great respect for local law enforcement. As much as he’d like more thorough updates, he doesn’t expect to get too many.

“I think that, at this point now, for how far into this it is, that it's going to be pretty tight-lipped until there is a definitive answer,” he says. “I think that, after them already kind of kicking the mule with the whole ‘This was a targeted event’ ... then, you know, backstepping that, I don't know that they are going to open their mouths again until they have a definitive answer for things.”

No one seems to think police are particularly close to those answers, and that’s “the worst part for the community,” Mr Johnson says.

“What makes them so uneasy is just not knowing and also having the feeling that our law enforcement doesn’t know,” he says. “That’s what I get from their messaging. You know, they wouldn’t be reaching out so hard for help if they had some sort of line to work with.”

He’s referring to repeated appeals from authority and victims’ families for tips, surveillance footage and, basically, any information whatsoever. Just a few hours after Mr Johnson spoke with The Independent, police issued yet another appeal - asking people to come forward if they had any details about an alleged stalker Kaylee Goncalves may or may not have had.

Police “have pursued hundreds of pieces of information related to this topic and have not been able to verify or identify a stalker,” MPD said in a Facebook update.

The stalker reports are among countless theories and facets surrounding the murder investigation, and none of them makes anyone feel any safer.

Valarie James, 21, was born and raised in Moscow and usually revels in the quietness of the holidays, when campus has emptied out and traffic lightens up. The University of Idaho is the town’s largest employer, and students account for nearly half of Moscow’s population.

The calm this year, however, is eerily different.

“It feels very tense around here, definitely, with the police presence everywhere,” Ms James tells The Independent. “People are a lot more, like, looking over their shoulder ... [there’s] a lot less friendly vibes, I guess, if that makes any sense.”

A colleague of Mr Combs, she’s dealing with the revolving door of customers as the locksmith labours at his station to fill the orders.

“They need to either give us more information or catch the guy before Thanksgiving break is over,” he tells The Independent. “Because there's a lot of students that won't come back.”

The university itself has said as much; UI has seen an uptick of an enrollment - nearly 5 per cent last year - but the brutal slayings, particularly if lef unsolved, could easily reverse that trend.

“We are making security our top priority,” U of I President C. Scott Green said on 20 November at a press conference that raised more questions than answers. “We are also planning for the very real possibility that some students aren’t comfortable returning to campus. We will do our best to meet the needs of all students.”

The administration has made various resources available to nervous and traumatized students; at Moscow Tattoo Company, Mr Johnson volunteers that his wife works at UI’s Counseling and Testing Center. He expected her to be swamped, but he says she seems less busy than before - because “a day after this happened, 80% of the students kick rocks.”

Many locals compared the vibe and emptiness of the town to the depths of the pandemic - with some claiming it’s even worse now.

The desertion was markedly different, both Mr Bartels and Mr Johnson say, for just how “rapidly” it occurred.

“It was a mass exodus very quickly this time,” the tattoo artist says.

Those who remain are staying vigilant - and buying locks - as they follow cops’ vague advice; those who’ve left are grieving from afar.

Everyone is hoping for an arrest and justice for the tragic four young students. After more than three weeks without answers and little announced progress, however, no one knows when - or if - that justice might come.

This story was originally published on 22 November.