‘Just following orders’ defence and blue wall of silence failed officers convicted over George Floyd’s death

J. Alexander Kueng, Tou Thao and Thomas Lane each took a similar line of defence in their federal trial for violating George Floyd’s civil rights: that they were ‘just following orders’. It didn’t work. Rachel Sharp reports

“You don’t think about it, you don’t second guess it, you just follow it.”

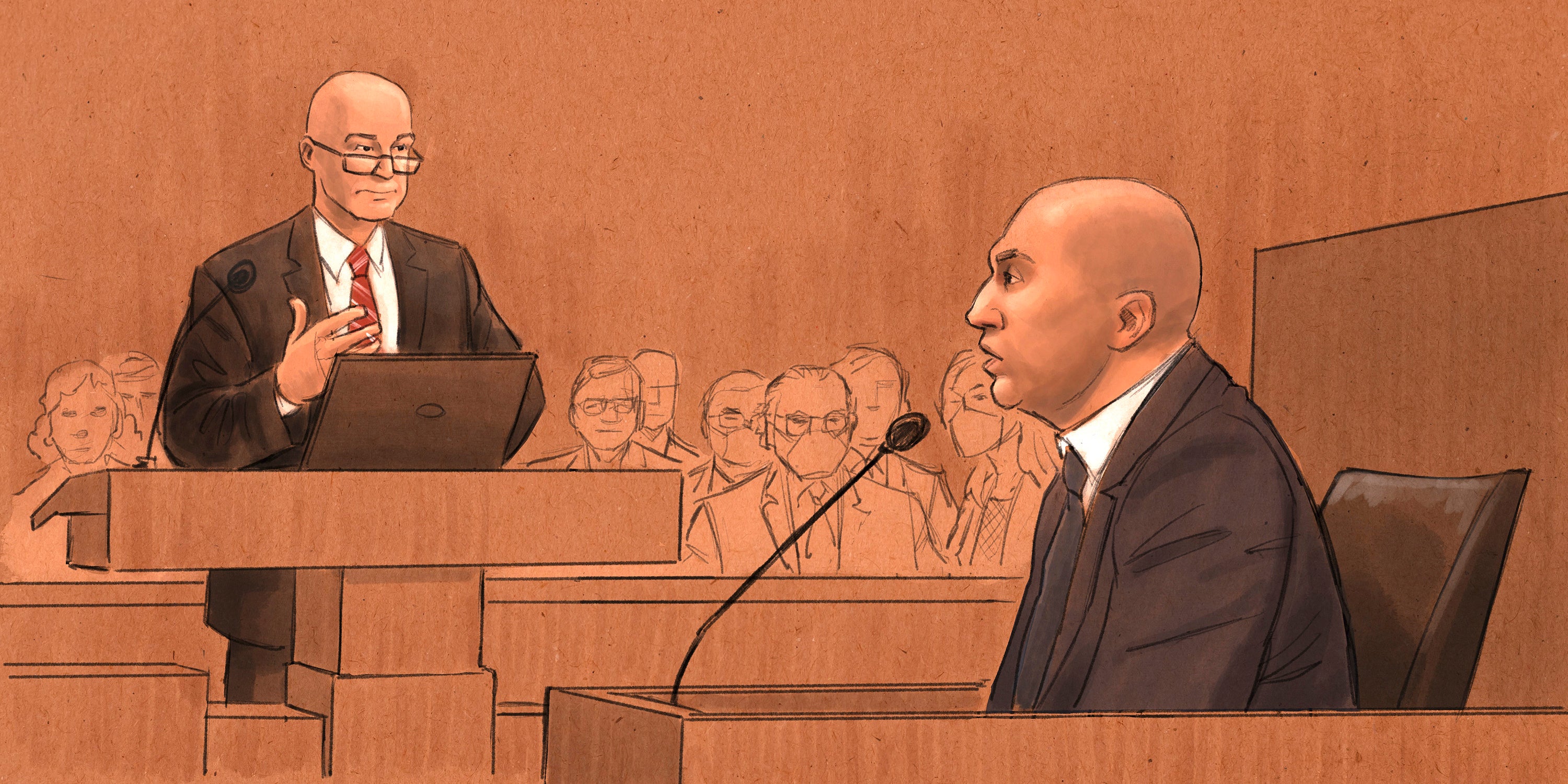

That was the testimony from J. Alexander Kueng about following the orders of Derek Chauvin while the more senior officer murdered George Floyd.

Mr Kueng was responding to his attorney after he was presented with a section in the Minneapolis Police Department’s training manual that read “instant and unquestioned obedience is demanded” from junior officers.

Under cross-examination, he doubled down about how he deferred to “role model” Chauvin.

“He was my senior officer and I trusted his advice,” he said.

It’s a line of defence that all three former Minneapolis police officers on federal trial for violating George Floyd’s civil rights have argued: that they were simply following the orders of the most senior officer on the scene.

But it didn’t work.

On Thursday, Mr Kueng, Thomas Lane and Tou Thao were found guilty of all charges against them in the federal court.

Mr Thao and Mr Kueng were both convicted of two counts - one for depriving Mr Floyd of his civil rights by failing to provide him with medical care and one for depriving Mr Floyd of his civil rights by failing to intervene to stop Chauvin’s unreasonable use of force.

Mr Lane was found guilty on the one count of depriving Mr Floyd of his civil rights by failing to provide him with medical care.

The jury also found that the officers’ actions had resulted in Mr Floyd’s death, meaning they face higher sentences.

Throughout their month-long trial, much was made of the experience of the respective officers, with both Mr Kueng and Mr Lane just days into their jobs as fully trained members of the Minneapolis Police Department.

They had undergone training for around a year, during which time 19-year veteran Chauvin acted as Mr Kueng’s field training officer (FTO) up until just a few days before Mr Floyd’s murder.

“I knew that he was an FTO and I knew of his reputation that he’d been on for 20 years and was a guy that had been in a lot of serious situations and could handle himself,” Mr Lane said of Chauvin when he too took the stand.

In his attempt to shift the blame onto Chauvin, Mr Lane testified how he had asked him twice if they should roll Mr Floyd onto his side - in line with his training.

Both times he said his suggestions were “deflected” and he was told “no” by the veteran officer, leading him to think their position pinning the Black man face down on the ground must be “reasonable”.

While Mr Thao had been on the force for eight years himself, he too repeatedly referred to the “19-year veteran” as his reason for not bringing a stop to Mr Floyd’s murder.

“I think I would trust a 19-year veteran to figure it out,” he snapped at one point when the prosecutor asked why he didn’t tell Chauvin to get off the Black man’s neck.

By contrast, his reasoning for not acting on the concerns of bystanders who repeatedly raised fears that Mr Floyd was dying and begged the officers to administer medical aid was: “I don’t take orders from them.”

It’s a line of defence that the prosecution poured cold water on, telling jurors that the three former officers “chose to do nothing” to try to save Mr Floyd and to stop Chauvin from murdering him.

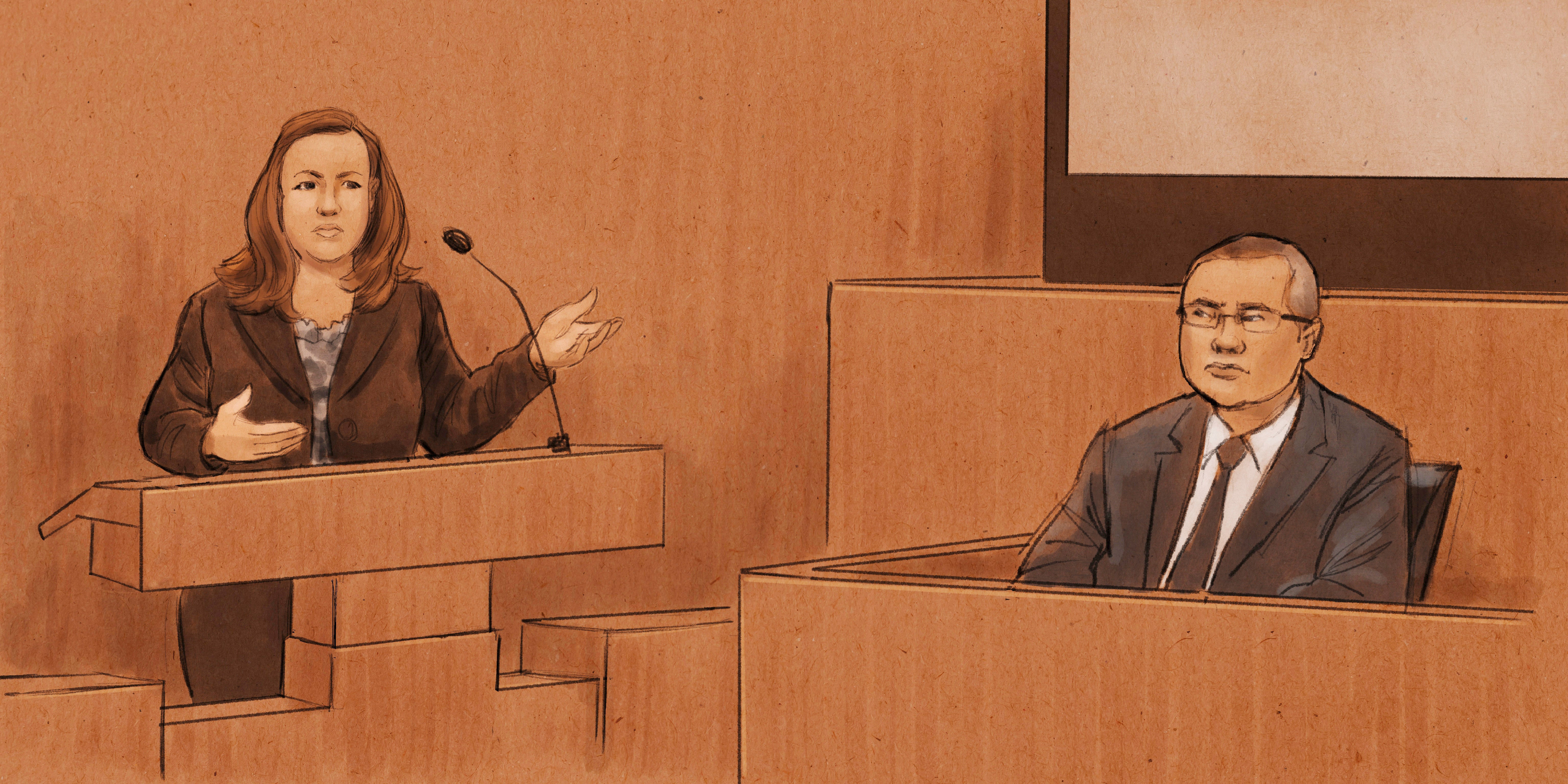

“Officer Chauvin isn’t ordering these defendants around, he’s barely talking to them,” said prosecutor Manda Sertich.

“The officers knew George Floyd couldn’t breathe and was dying.”

It’s also a line of defence that’s been heard before.

The Nuremberg defence

Following the defeat of the Nazis to the Allied Forces in World War Two, military tribunals were held in Nuremberg to prosecute prominent members of the Nazi party.

Very few of those on trial denied their involvement in the persecution and murders of millions of Jewish people.

Instead, their defence was that they were “just following orders”.

Rudolf Höss, the commandant of the Auschwitz concentration camp where over one million people were killed, told the court at his trial: “We were all so trained to obey orders without even thinking, that the thought of disobeying an order would simply never have occurred to anybody.”

The judges rejected their defence and, ever since, the superior orders argument has been widely known as the Nuremberg defence.

Azadeh Aalai, assistant professor in psychology at Queensborough Community College at CUNY, said she was “surprised” to hear the former police officers resorting to a similar argument at their trial.

“I think it’s kind of curious as it’s a weak defence that was largely rejected during the Nuremberg trials,” she told The Independent in an interview prior to the verdict.

“[At Nuremberg], the judges pushed back and were like ‘well what if you specifically were ordered to shoot your own parents, would you obey that order?’ and the perpetrators were like ‘absolutely not’.

“So the ‘just following orders’ defence and the notion that people don’t have a choice just totally falls apart.”

While Professor Aalai said the argument is “weak”, she said that there are situations where people are more likely to do bad things under the orders of others.

Obedience to authority

The most famous example was carried out by Yale University psychologist Stanley Milgram back in the 1960s.

Participants were told to administer electric shocks to a person in another room every time they made a mistake in a task. They were told the shocks would increase in voltage each time.

The experiment, which began just one year after the trial of Holocaust organizer Adolf Eichmann, aimed to test the conflict between an individual’s obedience to authority and their own personal conscience.

The most well-known version of the experiment saw the vast majority of participants administering shocks all the way up to what they believed was the highest voltage of 450 volts.

The study is often referenced as disturbing evidence that anyone is capable of inflicting harm on another person when ordered to do so by an authority figure.

However, what many people don’t realise, said Professor Aalai, is that the study actually involved a series of different experiments with various situational factors - and varying outcomes.

“The translation of this study to blind obedience to authority is overly simplistic,” she explained.

“What it actually showed was that different factors influence to what extent people are obedient in different situations.”

The presence of an authority figure is one factor that can lead to increased obedience, said Professor Aalai.

“When the man in a white lab coat was in the room, participants were more obedient. When the man in the lab coat left the room temporarily and said ‘continue giving the shocks without me until I’m back’ people were likely to disobey,” she said.

“So the rookie officers were more likely to obey and go along with what was happening as Chauvin was present and their status as officers was lower [than his].

“But what’s surprising is that there was also bystanders there trying to intervene and the officers still took part.”

During the 9 minutes and 29 seconds that the life was squeezed out of Mr Floyd by Chauvin’s knee, a crowd of local residents, passers-by and even off-duty first responders had gathered around the scene.

Many were telling the officers that the Black man was dying and begging them to get off him and give him medical attention.

One bystander, Darnella Frazier, filmed the murder on her cellphone and the footage has since been watched millions of times across the globe.

Professor Aalai explained that the pressure from the large crowd and the fact the incident was being filmed should have increased the sense of responsibility felt by the officers.

“That could give more of a sense of responsibility and alter their behaviour,” she said.

“It’s surprising that even with the immediate pressure from people telling them to stop they didn’t,” she said, adding that this actually shows “more readiness to get involved in what was happening”.

Mr Kueng claimed on the witness stand that he feared Chauvin could have him fired from his job if he disagreed with his commands.

In the Nuremberg trials, the defendants also argued that they feared there would be negative consequences if they disobeyed orders.

Professor Aalai said that the likeliness of obedience can increase when there is a fear of negative consequences if they disobey but, in both cases, the level of consequence is vastly different to the consequences of their own actions.

“There was not a single case where the Nazi perpetrator’s life was at risk if they didn’t go through with killing others,” she said.

“Yes, there were negative consequences but these negative consequences were not life threatening and weren’t to the extent that they were coerced into these behaviours.”

In a similar sense, the potential negative consequence put forward by Mr Kueng if he disobeyed Chauvin - losing his job - was far less significant than the consequence of his purported obedience - the loss of Mr Floyd’s life.

As such, the “just following orders” defence “falls apart”, said Professor Aalai.

“There’s a recognition that there is a line and a boundary and that there are actual acts that, even if a superior tells you to do, you would disobey,” she said.

Under cross-examination, it appeared that Mr Lane agreed.

“You would agree that fear of negative repercussions, fear of angering a field training officer is not an exception to the duty to render aid,” the prosecutor asked.

“Yes, ma’am,” he responded.

Hierarchies in policing

Nour Kteily, Northwestern University professor and expert in power hierarchies, is also not convinced that the obedience argument holds up in the officers’ trial.

“I don’t think Chauvin was necessarily giving orders,” he told The Independent as the trial was ongoing.

“That would be where the authority figure is compelling them to behave in a certain way.”

The case does however shine a spotlight on the psychology of authority and hierarchy - particularly within policing.

“Humans are social animals so we learn a great deal about how to act through social norms,” he said.

“We look to other people and follow their leads when we don’t know how to act in situations.”

It’s no secret that authority and hierarchy are especially deeply entrenched within law enforcement.

Which means that police departments can breed environments where people are greatly influenced by authority and reluctant to stand up to superiors.

Mr Kueng sought to blame this “hierarchy” for his failure to stop Chauvin, saying there was “an unofficial rule for seniority” in the police department and that “it’s commonly known there is a hierarchy”.

“It doesn’t necessarily go from one to the other that if you have hierarchy then people will be complicit,” said Professor Kteily.

“But it certainly creates additional pressures and people have greater potential to exert authority over junior people.”

The ‘Hollywood’ version

Eugene O’Donnell, former NYPD officer and professor in the criminal justice department at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, said that rookie officers are expected to follow the orders of their superiors.

“Younger, junior officers are in this hierarchical, rigid setting where they are disempowered and where there is deference to people who claim to be more senior and therefore more skilled,” he told The Independent.

“But more senior doesn’t mean more skilled and there is a bad dynamic in policing that the more senior person sometimes tries to put on a show for the junior people.”

That said, Professor O’Donnell called the idea that this hierarchical culture creates a situation where officers are reluctant to stand up to senior officers when they use excessive force “the Hollywood version” of police culture.

“One of the cultural falsehoods is that police officers are this elite, select group of people who are highly trained and where there are protocols for everything and when things go wrong it’s because there has been a deviation from these protocols,” he said.

“That’s nonsense. The reality of policing is that a lot of people are making it up in real time and doing the best they can in a complex situation.”

What they didn’t do

When it comes to a person’s sense of moral judgement and personal responsibility in a situation, Professor Kteily said that the trial of the three officers shows how a distinction is made between omission and commission - what someone fails to do versus what they did do.

“People often have the impression that if they fail to act, they are less culpable than someone who chooses to act,” he said.

“When people judge someone’s moral judgement they see a difference when someone acts in commission versus omission.”

The charges in the civil rights trial against the three officers were focused on this sense of omission.

They were not charged over the actions they took in the lead up to and during Mr Floyd’s killing.

They were charged over what they didn’t do.

All three were accused of violating Mr Floyd’s civil rights by failing to provide him with medical care as he lay dying under Chauvin’s knee.

Mr Kueng and Mr Thao were also charged with failing to stop Chauvin from murdering Floyd.

Police officers have had a duty to intervene against their fellow officers when they are using excessive force long before the murder of Mr Floyd.

Dismantling the blue wall of silence

However, in reality, police departments have long stuck to an alternate, unofficial rule: the so-called “blue wall of silence”.

The blue wall of silence is an unofficial pact that police officers have to not speak up or report their fellow officers.

A sense of loyalty that sees officers close rank around each other when a colleague is accused of wrongdoing.

“We know there is a lot of pressure to show solidarity and loyalty among officers,” said Professor Aalai.

“And there’s been very few cases of accountability in policing where officers have felt the consequences of bad behaviour.

“So there is a sense of impunity that law enforcement gets away with things and if you speak out you risk being ostracised from your colleagues - so are you going to speak up or go along with it?”

Professor Kteily said that the adversity between law enforcement and communities can actually make this wall stronger.

“If an entity is under criticism from the outside, the culture can get tighter and seek to protect itself even more so you have this code of silence inside,” he said.

Back on Memorial Day 2020, all four officers stuck together as the crowd begged the officers to help Mr Floyd.

Mr Thao’s, Mr Lane’s and Mr Kueng’s sense of duty to Chauvin appeared to override their duty to protect Mr Floyd, said Professor Kteily.

“But does that mean that no other psychological forces are countering this? No,” he said.

“A sense of moral duty and obligation could override those forces.”

Mr Floyd’s death and Chauvin’s murder conviction triggered the start of the dismantling of this wall of silence and signalled change in the longstanding police culture that enabled his death to happen.

At Chauvin’s trial, police officers including then-Minneapolis Police Chief Medaria Arradondo broke rank and testified against their former colleague.

And several also testified at the trial of Mr Lane, Mr Kueng and Mr Thao.

Minneapolis Police Department Inspector Katie Blackwell took the stand over three days, telling the court that the three officers were fully trained by the department - including in its “duty to intervene” policy - and that they “have an obligation” to stop or try to stop other officers if they see them using excessive force.

Richard Zimmerman, the head of the Minneapolis Police Department’s homicide unit, also testified that “if you see another officer using too much force or doing something illegal, you need to intervene and stop it”.

Beyond the courtroom, police departments all across the country have introduced new policies or strengthened existing ones on a duty to intervene in the wake of Mr Floyd’s murder.

In the one-year aftermath, 21 of the nation’s 100 largest police agencies created duty to intervene policies for the first time, according to the Brennan Center for Justice.

A dozen states and Washington DC also took statewide action including implementing penalties - such as criminal prosecution - for officers who fail in their duty to intervene.

Such policies are powerful in sending a message to police officers that there are far bigger consequences than being ostracised by colleagues if they turn a blind eye to excessive force, said Professor Aalai.

“It’s an important nuance,” she said.

“Changing culture is less tangible and will take longer but policy implementation is quicker and if there are more obvious consequences this will disincentivise those behaviours.”

The same could be said for the verdict of this trial, she added.

Given Thursday’s conviction on all charges, it seems “we were just following orders” no longer has a place in modern policing.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks