‘It feels like it happens every week’: Nashville grapples with gun debate after school shooting massacre

Less than a year after 19 children and two teachers were killed by a teenage gunman in Uvalde, Texas, a 28-year-old shooter killed three children and three adults more than 1,000 miles away in Tennessee. Nashville has been added to the list of tragic school shooting sites, as the famed Music City grapples with grief, God and the gun debate, writes Sheila Flynn

Middle school basketball, it seems, would mark one of the most defining and cherished chapters of Audrey Hale’s short life.

Hale played on a fierce team whose success was all the more impressive for its home at Isaiah T Cresswell Middle School of the Arts. The players welcomed with kindness their shier, more awkward teammate, and Hale repaid them with a lifelong adulation; the fledgling artist spent a decade and a half dreaming of, drawing and trying to contact the girls who’d made such an impression as together they entered adolescence.

Then, on Monday, Hale stormed into a Christian school with arms and an agenda, shooting dead three children just a little younger than the ages of those friends when they’d all shared a court years ago.

One of those former teammates, concerned by a Monday message from Hale, was on the phone with authorities as the attack unfolded.

“I cannot BELIEVE this,” the friend posted on Facebook soon after. “SPEECHLESS!”

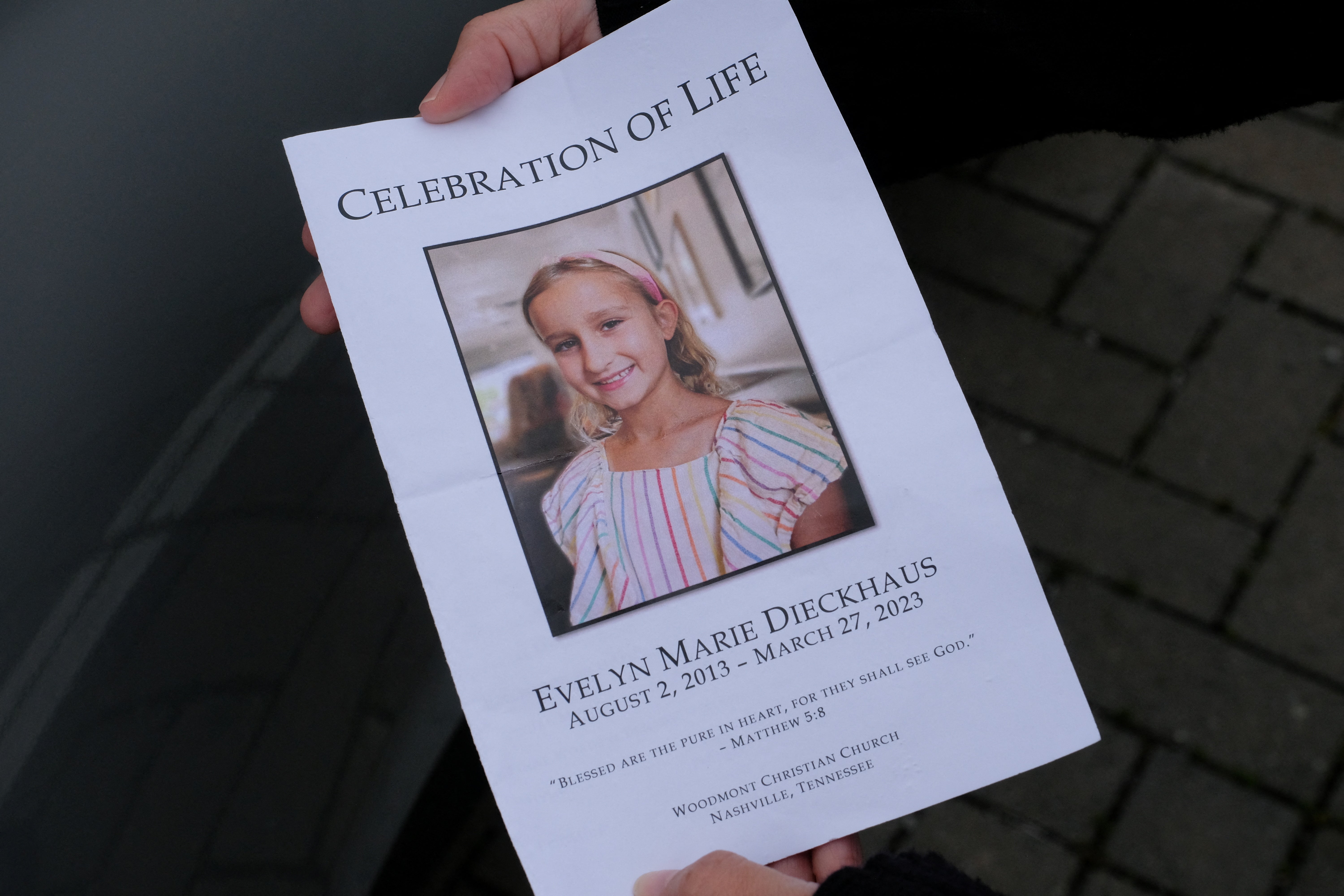

The wider community in Nashville reacted with equally shocked horror, still numb days later as thousands began attending memorials and funerals for the victims. At a “celebration of life” on Friday for victim Evelyn Dieckhaus, 9, Rev. Farrell Mason admitted to the congregation that the school massacre had left her consulting her own handwritten tenets of faith, asking God how something so tragic could happen.

She found comfort, she said -- as Evelyn’s grieving family sat in the front pews -- in community, hope, faith, love and God.

But answers remain elusive.

There is still no publicly known motive behind the attack on The Covenant School by Hale, who had enrolled there in the third and fourth grade before transferring to Cresswell and its beloved basketball team. Armed with three guns, Hale shot through the glass the school doors in the upscale neighbourhood of Green Hills, killing 9-year-olds Evelyn Dieckhaus, William Kinney and Hallie Scruggs along with head of school Kathleen Koonce, 60; substitute teacher Cynthia Peak, 61; and custodian Mike Hill, 61.

They’d gone to school without a thought on Monday morning, Mr Hill – known as Big Mike – looking forward to the halls he’d presided over for decades. Ms Peak, a friend of the governor’s wife, was preparing for a dinner later that evening with the First Lady of the state. Students were excited about and practicing for a Friday school play, when third-grader Evelyn was set to sing What A Wonderful World.

Before the end of the day, the names of the three child victims and three adults would be permanently etched into the memories of their city, state and country. So would the name of the 28-year-old shooter, who was killed by police within 15 minutes of the start of the attack.

In the days following the tragedy, in the midst of the disbelief and grief, there was another emotion oft repeated -- a pride in the swift response of law enforcement, a relief that not more victims had been killed and wounded. The undercurrent was clear as people searched for any positive after the unimaginable events: Nashville reacted better than Uvalde.

Monday’s attack came less than a year after a teen shooter killed 19 students and two teachers in Uvalde, Texas -- the devastation magnified by revelations that heavily-armed officers waited for more than an hour before confronting the suspect.

Nashville law enforcement, undeniably, handled the Covenant School shooting much more quickly and heroically. But the comparison begs a deeper and more depressing question: In what type of a world are we living when there’s even an opportunity to categorize school shootings as “better” or “worse?”

The question was not lost on Nashville, which, until this week, had escaped relatively unscathed amidst the escalating rash of gun violence in schools. Tennessee has some of the most lax firearms laws in America, and the state is also deeply Christian; in this part of the world, God and guns often go hand in hand. Republican Congressman Andy Ogles -- who represents the district where The Covenant School is located and has served on the board of Vote for Faith -- sent out a Christmas card in 2021 featuring his family posing in front of their decorated tree, all but the youngest child carrying rifles.

That photo came back to bite him in the behind this week, as outraged protesters plastered it on posters demanding change on the grounds of the State Capitol. Mr Ogles has not apologized, and there are still those who argue that more guns are needed to protect children from shooters. Some in Nashville were querying why Covenant -- where tuition costs around $16,000 a year -- didn’t have more designated armed security.

But most Nashville residents, particularly parents and students themselves, wondered: Why should they have to?

“There’s a deep sense of misery and exhaustion, especially among high schoolers,” Willis Egan, 15, told The Independent as he attended a candlelight vigil for the victims on Wednesday. “Seeing the kids in my school ... it’s not even shocking anymore. It’s just sadness. There’s kind of like a numbness to this. It feels like it happens every week.”

His 23-year-old-sister, El, said she worries on a daily basis for her little brother and their middle sibling, 18.

“I remember so vividly when Sandy Hook happened; I think I was 12 or 13,” she said, referencing the 2012 Connecticut school shooting that left 20 elementary schoolers dead. “And I just remember sitting on the couch with my mom and just sobbing, sobbing, sobbing ... curled up in a ball. And I was like, ‘I don’t understand. This doesn’t make any sense. I don’t understand how somebody could do that. Why would you want to take the lives of children? Why would you do that?’

“It just didn’t make any sense -- and then every year it gets worse,” she said. “We can do what we can and stage walkouts at school, we can march the streets and we can take part in these protests and stuff, but they’re not listening. Nobody’s listening. Nothing’s changing.”

The morning after Ms Egan expressed her outrage, S’Kaila Colbert brought her one-year-old daughter, Kadence, to a rally for gun reform at the Capitol. Unlike the conservatives who seem wedded to gun rights, Ms Colbert focussed on two key tenets of Christianity -- peace and love -- for her own arguments.

“It’s heavy; it’s frustrating,” she told The Independent, saying she came to the rally with “a sense of hopelessness, as a mom ... and, as a believer of Jesus Christ, having to have that hope that the people will be heard and that our children will be valued.”

She continued: “I would love to see some policy change, some gun reform. And I think, really, it just comes down to having a heart to look at the safety and the well being of the people of the state, of the children of this state, and listening to the people.

“We are asking for what we want today; we’ve made our voices heard and known,” she said. “And so I really think that’s it’s on policymakers now to heed the people.”

There was a parallel conversation going on, meanwhile, about America’s need to better address mental health. Audrey Hale was being treated for an “emotional disorder,” according to authorities, and former teammates have spoken about the shooter’s past mental struggles. Hale’s parents have told police they didn’t believe their adult child did or should own guns at the time of the shooting, though Monday marked the first time Hale crossed the radar of law enforcement.

“I think we need more gun legislation, also more mental health support,” Nashville mother-of-two Terry Naylor told The Independent at a prayer vigil one day after the shooting. “We don’t have a lot of either one of those. And when you are in trouble mentally, and you can’t get to a mental health specialist easily or cheaply, but you can come across a gun within two seconds... it’s scary.”

Hale’s parents believed that the 28-year-old had, at one point, owned and sold a gun; for whatever reason, they believed that their child’s ownership of more weapons was a bad idea. The shooter’s former teammates, however, recalled no previous episodes of violence, despite a pattern of increasingly bizarre behaviour.

During the middle school basketball years, Hale was “super timid when we first met her,” Paige Patton -- who also goes by Averianna -- told The Tennessean this week.

“I’m trying to be as respectful and also as honest as possible,” Phillips said. “It felt obsessive. It felt like stalkerish behavior.”

“We felt she was shy,” echoed Mia Phillips, 28. “So we embraced her and really befriended her.”

After Cresswell, some teammates attended different high schools; Hale went to Nashville School of the Arts, then Nossi College of Art & Design. Her teammates knew Hale, who was assigned female at birth, as Audrey; more recently, it seems, the shooter had begun using male pronouns and utilizing online accounts with the first name “Aiden.”

Throughout all of this, however, it seems that Hale remained fixated on the middle school team. Ms Phillips told The Tennessean how Hale would occasionally reach out to reminisce, though she was unsure how her former teammate knew her new email and physical addresses. According to another classmate, Hale’s high school senior art show featured colored pencil drawings of the girls on the basketball team.

Just last year, Hale turned up uninvited to a birthday party attended by some former teammates, Ms Phillips told The Tennessean; everyone believed Hale was inexplicably pretending to be inebriated.

“Everybody was confused,” Ms Phillips said. “It was just rubbing us in a weird way of like, giving us a really negative feeling. It didn’t feel right.”

While “trying to be as respectful and also as honest as possible,” Phillips said that Hale’s behavior.over the years “felt obsessive” and “stalkerish.”

Hale’s fixation with the team and its members took another tragic turn last summer, when former teammate Sydney Sims was killed in a road accident.

“With much love to the family, I will miss my dear friend Sydney forever,” Hale commented on Ms Sims’ online obituary, in addition to apparently sending a gift. “Rise up Queen, You are Free!”

Hale’s social media posts about the death were so bereft that at least one former teacher mistakenly believed the pair had been romantically involved. Former classmate Samira Hardcastle, who knew both Hale and Ms Sims, told the New York Post that “Audrey was really heartbroken after it ... I just feel like she took it differently than some of us did.”

“She was still posting about Sydney almost daily,” Ms Hardcastle said, adding that Hale “really looked up to” Ms Sims with “maybe even infatuation.”

The barrage of posts was so bereft that at least one former teacher mistakenly thought the pair had been romantically involved. Ms Sims’ family declined to speak with The Independent, but her sister shared a private Instagram post with their hometown paper, detailing how Hale turned up to a family event following Ms SIms’ funeral.

“She then popped up uninvited to my sisters [sic] painting that my mom held a few weeks ago (Odd) and still don’t know how she found out,” she wrote to The Tennessean.

While Hale clearly considered the former teammates to be important close friends, that view was not reciprocated. As Hale matured and continued through adulthood, there seem to have been few, if any, close personal relationships in the future shooter’s life. Hale and a brother were raised by devout Christian parents in a well-heeled neighborhood; their mother, Norma, is listed on LinkedIn as coordinator of volunteers and meals team for The Village Chapel. a nondemoninational church just over three miles from the Covenant School and two and a half miles from the Hale family home.

Not a single relative or close friend of Hale has spoken in the wake of the Monday massacre. When reached briefly via phone by ABC that day, Norma Hale said it was “very, very difficult right now,” adding: “I think I lost my daughter today.”

Hale left a manifesto, though its contents have not yet been released; regardless of what the writings detail, locals cannot fathom how a lifelong member of their community -- a former Christian school student with no record who grew up right alongside their children -- could mow down unsuspecting innocents.

The shooter told Ms Patton, on the day of the attack, that “one day this will make more sense.”

“I’ve left more than enough evidence behind,” Hale wrote to Ms Patton. “But something bad is about to happen.”

Then Hale callously took six lives -- and shattered any feeling of security in Nashville’s schools and the city itself. Like in Uvalde, in Highland Park, at Michigan State, in Monterrey ... the same refrain kept echoing: This doesn’t happen here.

The day after the shooting, a 58-year-old teacher who works eight miles from Covenant said the same, calling Covenant, as a Christian school, “the least likely place you would have thought this would’ve happened” as she attended a vigil remembering the victims.

But the youth -- the students who worry about dying in class every day -- almost do expect it to happen.

And happen anywhere.

“I feel like it’s on the news every week, and even the small things make you nervous,” high school junior Eleanor Herrell told The Independent at the Thursday gun rally, adding: “It’s just scary.”

After most rally attendees had dispersed, a lone protestor stood on the steps of Nashville’s War Memorial Plaza, holding a sign above his head that read: “Don’t sell guns in stores.” Josh Weisler, 24, was at his coffee shop job on Monday when he noticed customers crying and heard about the shooting.

“To think that a child, they didn’t even get a chance to apply for a job yet because they’re young, they’re not [even] 16 ... it just breaks my heart, and it feels personal,” Mr Weisler told The Independent. “I don’t have children, but I want to one day -- and I want them to live in a world without guns.”

Bolstered by the optimism of youth, he insisted that his contemporaries and others were committed to changing the laws and the narrative.

“Hope is not lost,” he said. “My generation will continue to fight via love, via peace ... via protection.”

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks