Craig Robins: Meet Miami's Mr Gentrification - the man behind controversial $2bn art and fashion development

Some have complained the project is pushing up rents and threatening nearby neighbourhoods

.jpg)

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.If Craig Robins carries himself with something of a swagger, it is perhaps understandable.

In recent weeks, the developer credited with cleaning up Miami’s once no-go area of South Beach, has been showcasing his latest project, the city’s so-called Design District, an enterprise that brings together high-end fashion stores, restaurants, art galleries and architecture.

“My ambition was to make a place that, if you’re coming to Miami, this is something you really want to see,” he said. “The principles of urban design are central to the place, but the idea is to bring urban regeneration and design and architecture and art to make an impact.”

Mr Robins’ estimated $2 billion project to bring art, design and luxury goods to this part of north Miami has received considerable, positive coverage in the media and the charming 52-year-old courts the press. (The Independent was among a number of media organisations he invited to see the project.)

But it is not without controversy. In a manner that is repeated globally wherever gentrification takes place, the development of the district has reverberated outwards, pushing up rents in adjoining neighbourhoods, where developers are snapping up all available lots and buildings, according to a series of reports in the local media.

Those feeling this most powerfully are the residents of Little Haiti, an area to the north that over the past three decades has become home to immigrants those fleeing poverty and repression. Some in Little Haiti are now organising to try and save their community against what some there see as encroachment.

In an interview, Mr Robins, dressed in a pale lemon and wearing a straw Trilby, said visitors to the design district could see art, high end stores and design projects.

He claimed that those without deep pockets could walk around, drink a coffee, or see exciting art at locations such such the Miami Institute of Contemporary Art or De La Cruz Collection, which make no entry charge.

“This is a neighbourhood that people can just come and enjoy,” said Mr Robins, who was born and grew up in Miami and who founded his Dacra development and real estate company in 1987. He said his firm owned 70 per cent of the project, in partnership with L Real Estate.

A brief walk around the area, even on a hot afternoon, makes instantly clear why the development of an area that was once a pineapple farm has created such a buzz.

Among the fashion stores already open – many of them in striking, specially designed buildings built by international architects - are Prada, Armani, Cartier, Burberry, Christian Louboutin, Dior, Marc Jacobs, Max Mara and Louis Vuitton.

A large banner declares that Tom Ford will be be joining them soon. “Everything is coming here. It’s going to be great,” said one shop worker.

Four young women were window shopping, and visiting a dome designed by the late American architect Buckminster Fuller. All four were either studying architecture or else had recently graduated.

“It’s great that architects are getting paid to design because Miami needs more spaces and better buildings,” said 35-year-old Maria Peguero. “The downside is that a lot of people are getting pushed out. You can see signs and stickers that save ‘Save our neighbourhood”.”

A mile or so the north sits Little Haiti, a community that has grown over the past 30 years, swelled by series of migrations from Haiti, some legal, others not.

The taxi driver who drove The Independent, a man who gave his name as Frantz, said the development of the district had been both good and bad, depending on one’s perspective.

“There are jobs, and tourists who need taxis,” he said. “But there are also bad things. People will say they lost their house. It depends what side you are on.”

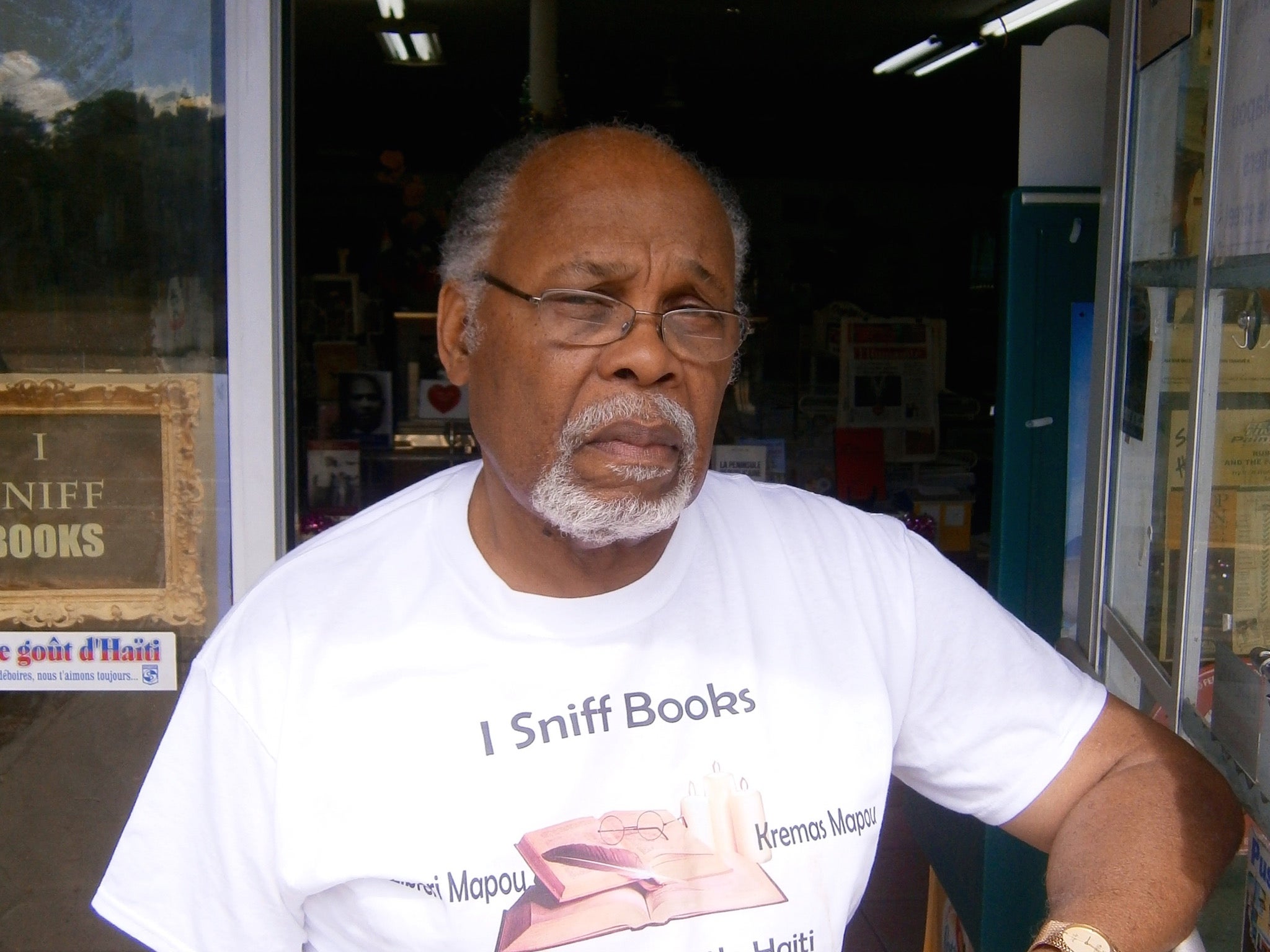

From the vantage point of the Libreri Mapou Book Store, owner Jan Mapou has witnessed life in Little Haiti for number of decades. He left Haiti in 1973, moving first to New York and then Florida.

He has run the book shop since 1990; now it stocks around 3,000 books in Creole, French and English, either about Haiti or else by Haitian writers.

He takes a nuanced view of development, and of the natural desire of first wave migrants to move out of the area they first moved into. Yet he said developers were moving into Little Haiti and buying up all available properties.

“It’s moving north. It’s going to absorb Little Haiti,” Mr Mapou said of the design district. “Maybe in ten years you won’t recognise Little Haiti.”

Mr Mapou said the impact of the development was to push up rents and create a sense of panic. He claimed the developers had failed to include the residents in their plans and said they had little political power to stand up, unlike other migrant communities in the city, such as Cuban Americans.

“We want to be included. We want to be part of it, and we want them to advise and talk to us,” he said. “Ten or so years ago, there used to be community meetings.”

Paul George, a professor of History at Miami-Dade College, said he believed the Design District development would help bring greater prosperity to Little Haiti, both from the property sales and from increased numbers of tourists and visitors who were currently wrongly fearful of the area.

But he said there would also be downsides, as there were wherever gentrification projects took place anywhere. “There is positive and negative,” he said. “It’s happening all over the world.”

The development of the design district is taking place at the intersection of art, fashion, politics and huge wealth. The showcasing of the development coincided with a gala dinner to celebrate the man awarded the Pritzker Architecture Prize, said to be the industry’s most prestigious.

The prize is funded by the Pritzker family of Chicago, reckoned to be worth $29bn but which in recent years has been rocked by a bitter family feud over inheritances.

Among those present were the judges, who included Indian industrialist Ratan Tata, Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer, developer and arts patron Lord Peter Palumbo, Chinese architect Yung Ho Chang and Richard Rogers. Guests included Elle McPherson Philip Levine, the Mayor of Miami Beach.

The prize of $100,000 has been awarded since 1979 to recognise living architects whose work has had signifiant impact. This year’s award went to the German Frei Otto, who died just days after the award was announced this spring. His daughter, Christine Kanstinger, accepted the prize on his behalf.

At a brunch for many of the guests, the morning after the gala dinner, Tom Pritzker, chairman of the prize board, said that Mr Robins had played a key role in “bringing the prize to Miami”. Mr Robins said he had known the Pritzkers since 1989 but that the family were not among those investing in the development.

Mr Robins said that while he was not among those firms buying properties in Little Haiti, he believed the development of the design district would benefit the surrounding areas. He said among those benefits was the option for those who owned homes to sell them and make a "meaningful" profit.

He added: “Having neighbourhoods transition can be a great thing when stakeholders can benefit of the long-term opportunities afforded by those changes.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments