Coronavirus: Maryland finally details how it will use 500,000 tests shipped from South Korea

State’s governor says local leaders have been requesting hundreds of thousands of kits for communities

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Maryland governor Larry Hogan, a Republican, announced the purchase of 500,000 coronavirus tests from South Korea last week, he called it “an exponential, game-changing step forward” in the state’s effort to get more people tested.

The dramatic story drew notice from Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden and a dismissive swipe from fellow Republican, Donald Trump.

But more than 10 days after the chartered Korean Air plane landed, Maryland has not allowed access to the tests kits, much to the frustration of local, state and federal leaders seeking to alleviate community testing shortages.

“None of the kits have been deployed, and no one knows when they will be,” Harford county executive Barry Glassman, a Republican, said on Tuesday afternoon. “In the environment that’s out there, that need is not being met.”

In conference calls with local and federal officials over the past two weeks, the Hogan administration said the tests were hung up by regulatory hurdles and shortages of other testing supplies that have throttled testing capacity nationwide, according to multiple people who participated.

Mr Hogan publicly described a different reality on Wednesday, when he outlined for the first time how he will use the tests. He said he would prioritise universal testing in nursing homes and other hot spots, such as an outbreak at a poultry plant on Maryland’s eastern shore.

The governor said the kits would also bolster testing for health-care workers and first responders. As a fifth priority, he would expand the broad, community-based testing experts say is critical to easing shutdown restrictions.

“As soon as we got the tests, everybody was like, ‘Can we have 100,000 of those tests?’” Mr Hogan said of local leaders. “First of all, the state is going to maintain those tests. We’re not just going to send them off to people.”

Mr Hogan's spokesman, Michael Ricci, said there is no imminent shortage of swabs or other testing supplies significant enough to limit output at state-controlled labs.

Two private labs have been contracted to use the South Korean kits, Mr Ricci said, and one cleared the necessary regulatory hurdle a week ago. Along with the state lab, he said, the private labs are adequately stocked to ramp up state testing to as much as 2,200 samples per day. This does not include capacity in hospital and commercial labs.

When asked why state officials offered different information in their closed-door conversations with county leaders and congressional staffers, another of Mr Hogan's aide said the administration has been cautious about conveying the extent of its resources while it is trying to secure additional testing supplies. The aide spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss internal strategies.

Additionally, despite the fanfare surrounding Mr Hogan’s $9.4m (£7.5m) dollar deal with LabGenomics, the test kits from Seoul were not in short supply in the United States, according to interviews with industry experts. Domestic manufacturers were producing millions of them per week when Maryland struck its overseas deal.

Some firms sell the kits for 20 to 30 per cent less than what Mr Hogan paid.

Mr Ricci said the state picked the Korean company weeks before the shipment arrived, when market conditions were different, “based on a number of factors, including compatibility with our labs, market availability, reasonable market price, delivery methods and coordination, and overall trust and communication with the vendor.”

On Tuesday afternoon, a state health department official told congressional staffers that Maryland was missing critical testing components and had only enough supplies on hand to conduct 3,200 tests in state-directed labs, according to multiple people on the call.

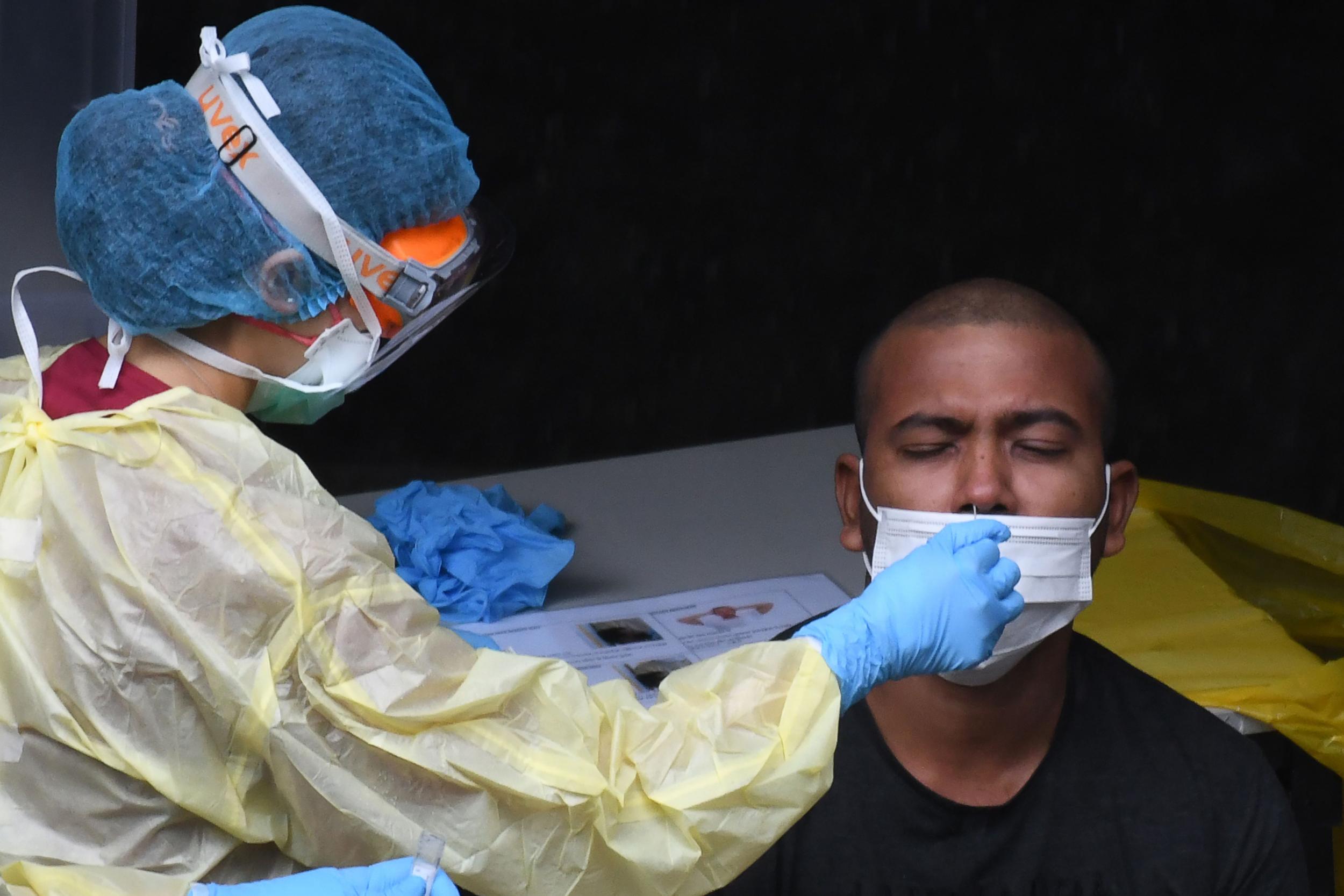

The state official described specific shortages in nasal swabs, viral transport media and reagents, outlining a scenario that would allow Maryland to use less than 1 per cent of the South Korean test kits.

State officials have offered no timetable for when the tests might be ready for community-based testing, according to interviews with local, state and federal officials involved in expanding Maryland’s testing efforts, which rank in the middle of the pack among states.

One official said leaders of some of Maryland’s largest jurisdictions have become so frustrated they’ve discussed trying to obtain their own tests since they can’t access the ones from South Korea. Experts say dramatically enhanced community-based testing is critical to understanding the spread of the virus. Without more testing, it’s impossible to identify, track and isolate new cases.

“If they have all of those pieces, it’s time to get them into the hands of people who need them,” the official said, who requested anonymity to be candid about private conversations. “We know there’s a need. These sitting in a state warehouse somewhere doesn’t do anyone any good.”

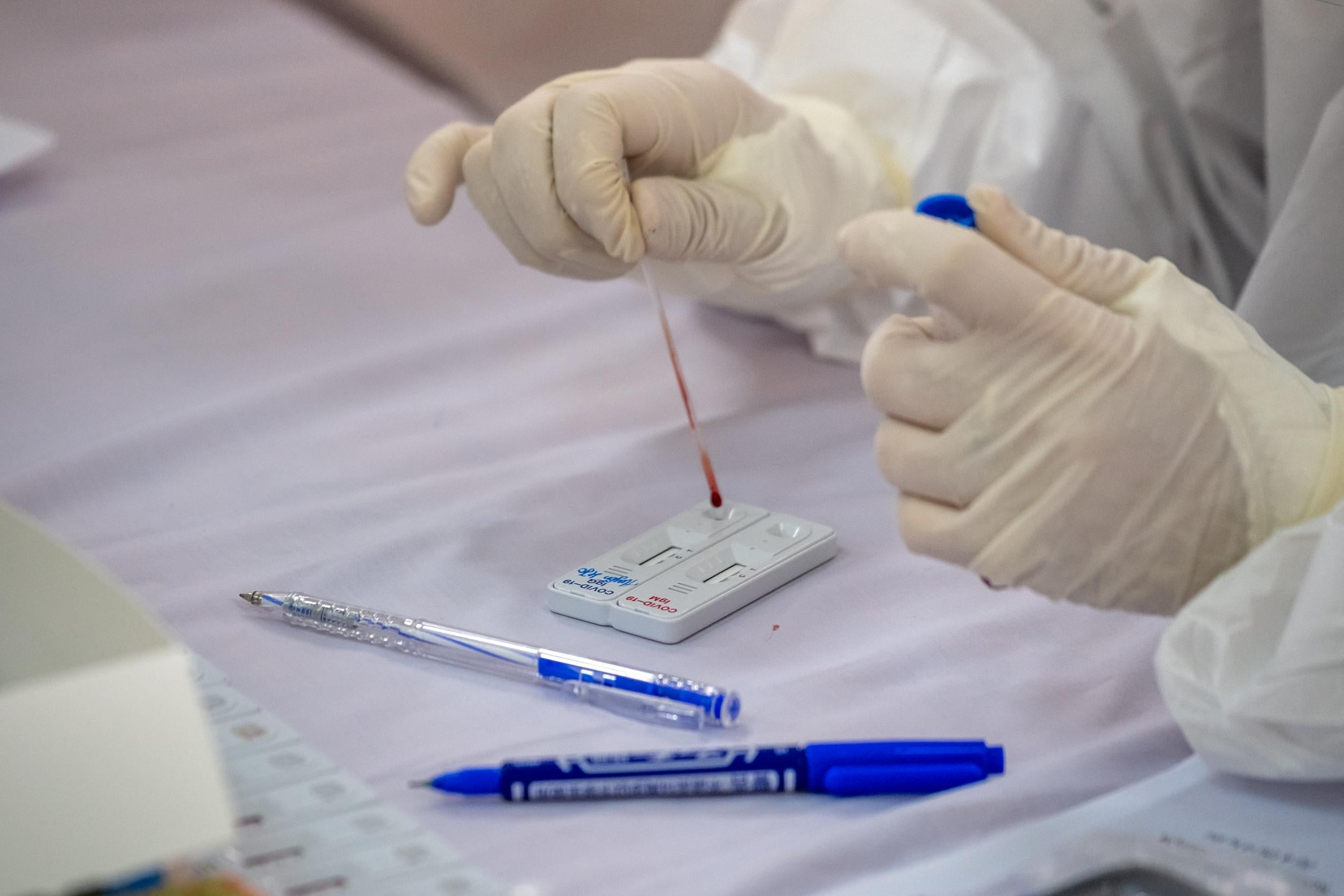

Local governments have worked to set up testing sites, where patient samples are collected via nasal swab and transferred to a lab for processing using the type of test kit Mr Hogan acquired. In general, those sites will only take as many samples as labs can process in a timely way.

Mr Hogan has said the South Korean tests are critical to meeting his goal of testing 10,000 people per day. At the news conference where he announced the purchase, he said he hoped to double that threshold, even as he acknowledged that the state would need more swabs, reagents and lab capacity to meet it.

Representative Anthony Brown, Democrat of Maryland, said Mr Hogan’s initial announcement led him to believe that Maryland was poised to implement widespread testing.

“What we learned over time is that’s not accurate,” Mr Brown said Wednesday. “A test means that you can take a sample and get a result, and he’s not able to do that for 500,000 Marylanders.”

Until the state can reach the ability to test 10,000 people per day, Mr Brown said, Maryland residents are “going to stay locked up in our homes”.

County leaders from the state’s major jurisdictions have been on at least two calls in the past 11 days with state officials, including with Mr Hogan himself, asking whether they can get some of the South Korean tests and when they can expand their own testing sites.

Baltimore County opened two new testing sites this week but is limiting the access to 320 people per week because labs cannot process more.

“The test kits from South Korea are just a piece of the puzzle and still need the appropriate swabs, reagents and lab capacity,” said Sean Naron, a spokesman for Baltimore county executive Johnny Olszewski, a Democrat. “We are still waiting on a clear timeline from the state on when all these pieces will come together.”

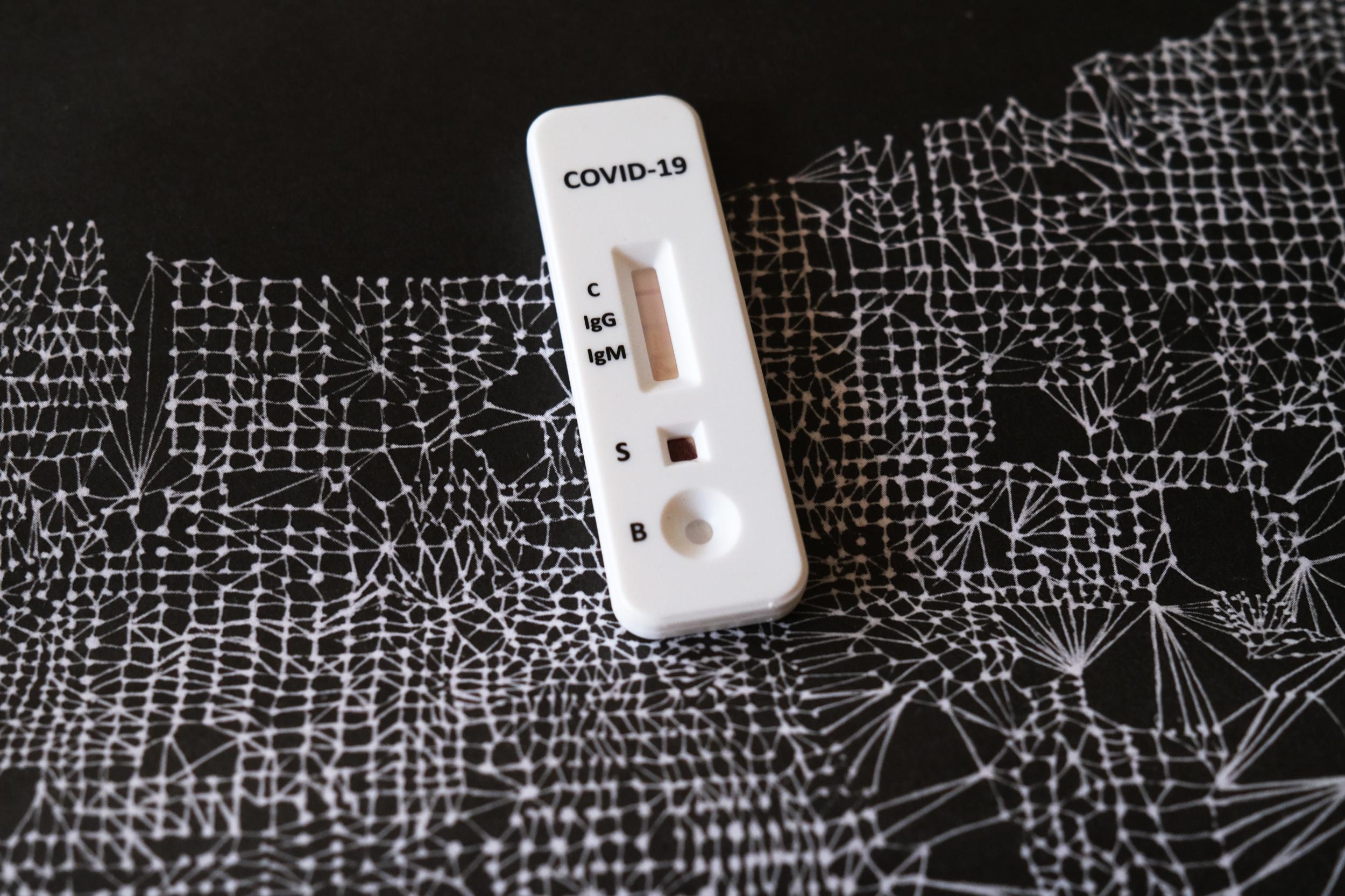

The South Korea test situation has devolved to the point that Montgomery county executive Marc Elrich, a Democrat, started laughing Wednesday when a reporter asked about access to the tests.“Without things like reagents,” Elrich said, “they are sort of like paperweights.”

Mr Hogan has consistently described his purchase of the tests as a necessary workaround after the federal government left it up to states to source their own testing programmes in circumstances that pitted governors against each other.

On The View, he said he had to go abroad to find “the test kits that nobody had enough of”.

In recent weeks, however, it has not been a shortage of the assays themselves that created national scarcities in testing, but the lack of the nasal swabs to collect samples and the chemical reagents to process them, experts say.

“If somebody had come to us a few weeks ago and said we need a large order for Maryland, we would have been very anxious and capable of taking the order and fulfilling it,” said Dwight Egan, CEO of a Co-Diagnostics, a company that makes the same type of assays Mr Hogan acquired from South Korea.

“We’re shipping to nearly 50 countries,” he said. “We always love to ship in the United States because it’s a lot easier to ship domestically than foreign.”

A distributor for Co-Diagnostics offered Maryland more than 500,000 tests at a cheaper cost during a call on 10 April, according to a person familiar with the pitch who requested anonymity to avoid scuttling future potential business.

Mr Ricci, Mr Hogan’s spokesman, said Maryland had signed a contract for the South Korean purchase just over a week before that, on 2 April. Mr Hogan has said he and his Korean-born wife, Yumi Hogan, began working on the deal on 28 March.

The state reached out to several domestic suppliers along with the Korean companies in late March, Mr Ricci said, but at the time none could offer the volume and guarantees the state was seeking.

The United States got off to a slow start in its efforts to test for the coronavirus after delays this year caused by federal red tape and an initial flawed test created by the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Other countries, such as Singapore, Taiwan and South Korea, ramped up more quickly. But US manufacturers worked fast to catch up.

By mid-March, US manufacturers were able to ship tests to domestic labs by the millions. On 18 March, Co-Diagnostics announced it could produce about 50,000 tests per day. Thermo Fisher Scientific announced on March 16 that it had 1.5 million tests on hand and expected to quickly increase production to 2 million tests per week, and the company has since reported it has ramped up to 5 million tests per week, many of which are being exported globally.

“No one is saying that they can’t get the test kits anymore. They’ve got those, and the manufacturers are certainly turning them out,” said Lâle White, chief executive of XIFIN, a health information technology company that services a substantial portion of the nation’s commercial and public diagnostic labs and produces industry analytics.

Eric Blank, chief programme officer for the Association of Public Health Laboratories, agreed. “As far as we can tell, there is not a shortage of the test kits,” Blank said in an emailed statement. “There are, and have been, shortages in the ancillary reagents and supplies like swabs throughout the response to date.”

Nevertheless, Maryland is not the only US entity to buy tests abroad. This month, the Federal Emergency Management Agency bought 600,000 tests from two South Korean companies for a total of $8.2m (£6.5m).

Mr Hogan initially said Maryland paid $9m (£7.2m) for its tests, a figure that state officials slightly revised upward Wednesday to $9,464,389 (£7,573,025).

That means Maryland paid $18.93 (£15.15) per test, while FEMA paid approximately $13.67 (£10.94).

In a statement, Mr Ricci said Maryland’s price “was considered reasonable based on market value”.

The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments