'He is in his element': How Bill Gates became the voice of the coronavirus pandemic

He has used his fame and wealth to push for science-based approaches to end Covid-19

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As the coronavirus pandemic rapidly spread across the United States in March, Bill Gates peppered his longtime friend Jeff Raikes with the science behind testing for the disease during dinner at his home in Medina, Washington.

The two men ate sushi – at an “appropriate” social distance, Raikes said – while Gates detailed the challenges of using nasopharyngeal swabs that reach deep into nasal passages to test for the novel coronavirus. Instead, Gates offered that self-testing with simpler, shorter swabs could be more effective and wouldn’t require health-care workers to risk infection themselves, said Raikes, a former senior leader at Microsoft who went on to run the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

“He is in his element right now,” said Raikes, who has worked closely with Gates for four decades.

As the virus has spread, killing more than 239,000 people globally, Gates has used his fame and wealth to push for science-based approaches to end the pandemic. Having studied infectious diseases for the past 20 years as part of his philanthropic work, Gates has warned about the potential for a pathogen-spread pandemic since 2015, in a TED Talk, lectures and medical journal articles. Since February, the foundation he runs with his wife has given away $250m (£199m) to expand testing for the coronavirus and find a cure for Covid-19, the disease it causes.

But the coronavirus is unlike any global health challenge Gates has faced. He’s spent years trying to address health threats vexing the developing world, such as malaria, polio and HIV. Those diseases have either vaccines or therapies, but the countries where they remain a major threat lack health systems to deliver them to people, something the Gates Foundation is trying to fix. When it comes to the coronavirus, though, there is neither a vaccine nor a therapy, and it’s spread to both rich and poor countries.

With the coronavirus afflicting rich countries as well as developing ones, Gates also needs to navigate the thickets of US politics. One new challenge for Gates: pressing messages that often run headlong into comments by President Donald Trump that lack scientific basis. In an interview, Gates noted past global health achievements by the United States, such as President George W Bush’s support for drugs to address the Aids epidemic sweeping across sub-Saharan Africa nearly two decades ago.

“People are hoping for US leadership. It’s still an opportunity we haven’t seized,” Gates said. “The vacuum of waiting for the US to step in and help out with that, there’s still a huge opportunity there.”

Gates hasn’t directly criticised Trump, and he remains largely apolitical. But research he has cited has undermined some of the president’s claims. The Gates Foundation, for example, is funding a clinical trial on hydroxychloroquine, the drug Trump that tweeted could, when combined with azithromycin, be “one of the biggest game-changers in the history of medicine.” Gates, though, focused on the data, writing in a 23 April blog post that early indications from the trial suggest “the benefits will be modest at best”.

Gates also took aim at the president’s plans in April to suspend payments to the World Health Organisation in response to the UN agency’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic.

“Halting funding for the World Health Organisation during a world health crisis is as dangerous as it sounds,” Gates tweeted on 14 April, arguing that the no other organisation is capable of replacing the agency. The Gates Foundation is the second-biggest donor to the WHO, after the US government.

“Bill is a guy who believes in science and technology and the positive impact that can have in the world,” Raikes said. “I think at least subconsciously, like many of us, he’s been disturbed by the attack on science,” though Raikes acknowledged that he hasn’t talked specifically with Gates about the topic.

Despite politicians’ calls to quickly reopen society that aren’t backed by science, Gates is not likely to become more political now, said Sue Desmond-Hellmann, the former chief executive of the Gates Foundation. Gates’ philanthropic work – addressing the vexing inequities in global health and US education systems – requires the support of governments.

“You have to pick your spots,” Desmond-Hellmann said. “Obviously, the WHO comment was of the magnitude that Bill and Melinda spoke out and said that the world needs the WHO.”

Gates famously dropped out of Harvard University to found Microsoft with his high school buddy, Paul Allen. But he is a voracious reader, and over the past two decades of his charitable focus on global health, he’s taught himself the science of infectious diseases.

“When I spend billions of dollars on something, I have a tendency to read a lot about it,” Gates said.

As Gates began to move away from Microsoft in the early 2000s, he gave a fireside chat to senior leaders at its Redmond, Washington, conference centre, discussing his foundation’s efforts to address malaria. Brad Smith, president of Microsoft, in particular recalled Gates’s “encyclopedic assessment” of mosquitoes, and how they behaved and transmitted the disease.

“I will always remember listening and thinking, ‘Oh, my gosh, he can go just in deep in talking about mosquitoes, as he did in talking about software code,’” said Smith, who has worked closely with Gates for 26 years.

Since the coronavirus first emerged in China late last year, Gates has consumed medical journal articles about testing, treatments and vaccines for the virus. He’s talked at length with immunologists, epidemiologists and social scientists about slowing the coronavirus’ spread.

“When Bill takes on an issue, he doesn’t seek to become just generally familiar with it,” Smith said.

Gates has met with presidents from both parties, including Trump. He has made campaign contributions to both Democrats and Republicans. Even when the federal government sued Microsoft for violating antitrust laws in the late 1990s, Gates refrained from publicly attacking the Clinton administration, which brought the suit.

With a net worth of $105bn (£83.9bn), Gates is the world’s second-wealthiest person, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index, behind his Seattle neighbour Jeff Bezos, the chief executive of Amazon and owner of The Washington Post. Gates has poured much of his wealth into the foundation he runs with his wife. It has become one of the world’s largest philanthropies, with an endowment of $46.8bn (£37.4bn) as of 2018.

Over the past two decades, he has gradually shed his Microsoft responsibilities to focus on philanthropic work. In March, he gave up the last of his formal Microsoft titles, stepping down from the company’s board, though he said he would continue to provide technology advice to its leadership.

A pillar of Gates’ philanthropic thrust has been addressing the infectious diseases, such as malaria and polio, that continue to devastate the developing world. His foundation helped create a market for drugs for those diseases, which were often ignored by a pharmaceutical industry that has a financial incentive to develop medication for ailments common in the more lucrative markets of the developed world.

His knowledge of infectious diseases led him to the conclusion in 2015 that a pathogen-based pandemic could sweep over the globe, killing indiscriminately and destroying economies.

“If anything kills over 10 million people in the next few decades, it’s most likely to be a highly infectious virus rather than a war,” Gates said in his TED Talk, which seems eerily prescient today.

He expressed concern that governments hadn’t invested in systems to stop a pandemic in the same way they financed nuclear deterrents. He encouraged the development of strong health systems in poor countries where he expected the outbreak to first emerge. He pushed for stepped-up research into and development of vaccines and diagnostic testing apparatus. And he called for “germ games,” akin to war games, to simulate a pandemic to help identify shortcomings.

“We need to get going because time is not on our side,” Gates said in the talk.

It’s an issue he has regularly raised with government leaders around the world. That warning largely fell on deaf ears. The lack of response is something Gates laments as “unfortunate”.

“I often think, ‘Could I have been more persuasive?’” Gates said.

The foundation invested in efforts to prepare for a pandemic even before Gates’ TED Talk. Leaders including Gates worried about the impact the Ebola outbreak in 2014 had on its global health work and spent hundreds of millions of dollars building scientific infrastructure that is now helping slow the spread of the disease.

In 2017, it gave $279m (£223m) to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, a group to which it had previously given funds. IHME has since developed a widely used forecasting model to predict the need hospital beds, ventilators and other medical equipment in every state and in countries around the globe.

The same year, the foundation committed nearly $100m (£79.9m) to help launch the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, which has been financing experimental research into coronavirus vaccines.

The 18-month-old, Gates-funded Seattle Flu Study research project tracks the spread of infectious diseases such as influenza. As the coronavirus outbreak was beginning to hit the United States, researchers with the project tested for the coronavirus even though it wasn’t what they were certified to do. They found one of the first US cases in a teenager who tested positive for the virus.

The project’s mission has evolved into the Seattle Coronavirus Assessment Network, which is conducting coronavirus testing with self-swab sampling kits that won’t expose health workers to the virus. That testing is now certified, and received approval for emergency use by the Washington State Department of Health.

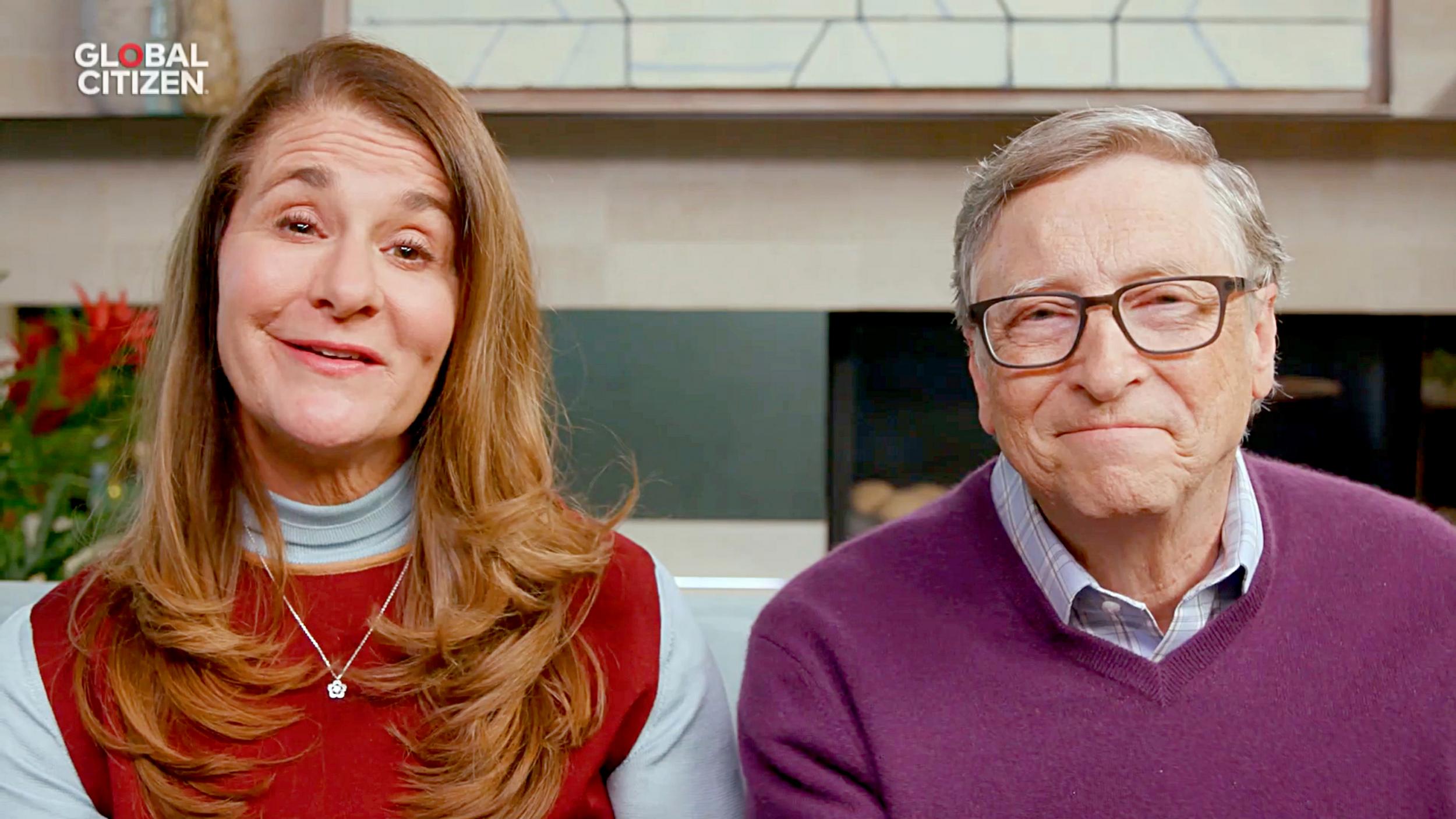

As the coronavirus spread, Gates has taken to the talk-show circuit, making his case for science-backed approaches. He chatted remotely on The Late Show With Stephen Colbert, lamenting the missed opportunities to have prepared for the pandemic. A few days earlier, he and his wife, Melinda, recorded a message aired during the One World: Together At Home global charity event expressing hope that a vaccine for the virus could emerge by the end of next year. That followed his video call with Ellen DeGeneres on her talk show in which he discussed the criteria for a return to normalcy.

His foundation’s global health efforts have allowed Gates to work with officials including Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health. Gates said he’s in frequent communication with both.

“I’m talking, actually quite a bit, to both Tony and Francis about what they’re seeing, what we’re seeing,” Gates said.

“My primary value add is finding out who the innovators are in understanding the system of scaling delivery that is necessary, like testing and contact tracing, which some countries are doing very, very well,” Gates said, bringing together scientists and researchers with whom the foundation is working and the government.

The Gates Foundation has faced past criticism for the outsize influence it wields in areas such as global health and public education. The massive sums that the foundation has put towards global health challenges has threatened to distort the way governments address those threats, encouraging them to adopt its priorities to receive its grants, according to research by Jeremy Youde, dean of the College of Liberal Arts and global health politics researcher at the University of Minnesota Duluth.

Youde acknowledged that the coronavirus pandemic is different. One reason: There’s so much money being poured into the public health crisis-from other philanthropies as well as pharmaceutical giants-that the Gates Foundation alone won’t determine the vaccine winners and losers. The pandemic illustrates “why it’s important to have these international collaborations,” Youde said.

There’s one group with whom Gates isn’t popular: the social media mob pushing conspiracy theories that the billionaire engineered the pandemic, and is mining it for profit and leveraging it for global surveillance and population control. His tweet about WHO funding cuts generated a flood of more than 75,000 comments, many questioning Gates’ motives and patriotism. Protesters at rallies pushing to end government lockdowns have waved signs railing against Gates.

Some conspiracy theories are being amplified by the Russian government, which is spreading misinformation about the coronavirus through “state proxy websites,” according to a State Department report. One article from early March on the website of the Zvezda television channel, a Russian state-controlled network run by the ministry of defence, claims that Gates played a role in creating the virus

“I got a note of sympathy from George Soros, so it must be getting serious,” Gates joked, referring to the liberal billionaire philanthropist who is a frequent target of conspiracy theories.

Gates, though, did have an early window into the spread of the virus. The foundation’s operations in China experienced firsthand the impact of the virus’ outbreak there, said Mark Suzman, the current chief executive. And it gathered information from the Seattle Flu Study’s work regarding the US spread.

“We got an early heads-up about that,” Suzman said. That led to the recognition that “we should be cranking up as a foundation very rapidly to see what we can do to help support” efforts to combat the outbreak.

In February, the foundation committed $100m (£79.9m) to improve detection, isolation and treatment efforts; to accelerate the development of vaccines, drugs and diagnostics; and to protect at-risk populations in Africa and South Asia. On 15 April, the foundation added an additional $150m (£119.9m) to that effort.

Gates recognises the need to spend billions of dollars to develop facilities to develop and manufacture vaccines, many of which won’t pan out. It makes most sense, Gates said, to waste money building for approaches that don’t ultimately work so that the vaccine that ultimately proves successful can be made and distributed rapidly around the globe, and end the economic devastation of the pandemic.

There’s a need to spend “billions to save trillions,” Gates said

The foundation won’t cover all of the cost of developing vaccines, Suzman said. But it can provide financing to quickly spin up manufacturing facilities.

“We’re a distinctive kind of capital. We can be risk-taking. We can be catalytic. We should never be in there substituting for public or private money, which could be doing the job just as well,” Suzman said.

While the foundation’s scope is broad – from eradicating polio to boosting college completion rates – Gates is now spending the predominant amount of his time on the pandemic, Suzman said. Non-coronavirus efforts have shrunk to about 10 per cent to 15 per cent of the discussion at the foundation. Emails from Gates dive deep into technical details about epidemiological modelling, vaccine constructs and what the cost of production per unit might be, Suzman said.

“All of the deep learning and expertise over the last 20 years of the foundation going into global health is very applicable to the current moment,” Suzman said.

And Gates doesn’t believe the call for pandemic preparedness will go unheeded any longer.

“I think this time people will pay attention,” Gates said.

The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments