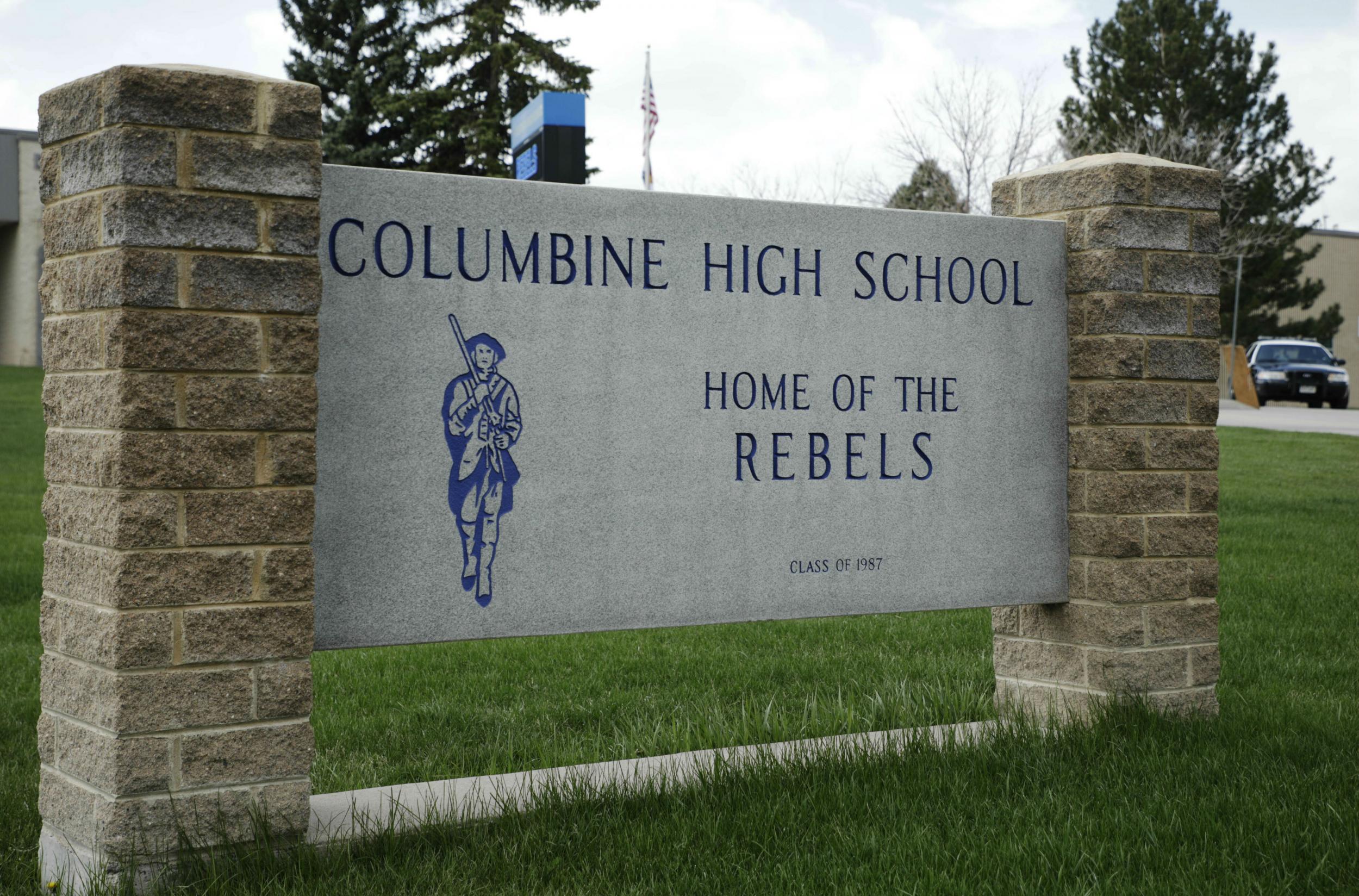

Columbine anniversary: How a notorious mass shooting forever changed the way Americans go to school

For the generation that followed, armed guards and active shooter drills are as commonplace as homework

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Like millions, Greg Crane, a supervisor of a Texas police SWAT team, watched in horror as the massacre at Colorado’s Columbine High School played out on television.

He was sad and angry, but also frustrated. Why should 12 pupils and one member of staff fall prey to two troubled teenagers armed with an arsenal of guns, he fumed. When his wife, an elementary school teacher, came home, he quizzed her about measures schools were trained to follow in an active shooter situation. Lock the classroom doors and wait for the cops, came the answer.

Two decades after the massacre at Columbine, as the nation pauses not just to remember the victims in Colorado – Cassie Bernall, 17, Steven Curnow, 14, Corey DePooter, 17, Kelly Fleming, 16, Matthew Kechter, 16 Daniel Mauser, 15, Daniel Rohrbough, 15, William “Dave” Sanders, a 47-year-old teacher, Rachel Scott, 17, Isaiah Shoels, 18, John Tomlin, 16, Lauren Townsend, 18, and 16-year-old Kyle Velasquez – but countless others, an active shooter response system designed by Mr Crane, is used in schools in all 50 states.

The protocol created by Mr Crane, based on his experience as a SWAT supervisor, has attracted controversy, and is not used universally. But the vast majority of school districts have rules on how to respond when there is an active shooter alert and pupils are regularly drilled. A report by the National Centre for Education Statistics said that in 2015-16, about 95 per cent of state schools ran lockdown drills.

The use of such drills increased rapidly in the years immediately after Columbine, even though data shows school shootings themselves have not markedly increased since then.

The post-Columbine generation of pupils was not the first to have performed such drills; during the Cold War, youngsters practised sitting under their desks in the event of a nuclear strike from the Soviet Union. But they were the first to have drilled into them, that their schools may suddenly be transformed into places of real, life-ending danger, not because of some distant enemy, but because of one of their classmates, armed with a semi-automatic weapon.

In the words of an Independent reporter who attended Twin Falls High School in Idaho 15 years ago, during lockdown drills an administrator would typically announce the lockdown – or “code red “ – over a loudspeaker.

“Students would then crouch under their desks, hide in closets if big enough, or crouch in the corner that would be least visible to anyone passing by outside,” he said.

“Teachers would lock the door – which is what one teacher at Parkland [the Florida neighbourhood where a student allegedly killed 17 pupils and staff at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in February 2018] was doing when they were shot – and students would then remain silent as administrators walked the halls, essentially acting as stand-ins for a shooter. It was as common as a fire drill.”

In Mr Crane’s system, which goes by the acronym Alice (alert, lockdown, inform, counter, evacuate), teachers and pupils are told not to allow themselves to be sitting victims. It stresses that they have “options”.

If they are shot at, they should zig zag. If a shooter is entering their classroom, they should consider leaping from a window. They should throw things at the gunman, or shout. They should try and get in his – for school shooters are almost without exception young men – head and distract him.

“The threat of an active shooter attack is rare but very real. We aim to eradicate the “It can’t happen to me” mentality and change the way people everywhere respond to armed intruders,” says the company website.

Mr Crane, whose system has been adopted by 14,000 school districts nationwide, said: “I realised that as a SWAT officer I could train as hard as I liked, and it would never be enough, because if a shooter enters a school, I simply cannot get there fast enough.”

The only solution was to try and prepare schools to be ready if an active shooter situation arose, he said. Mr Crane believes teachers and students can often do much more to reduce their chances of being killed.

“Let’s train everybody to do something, because the good guys always outnumbers the bad guys,” he said. “At Virginia Tech [a 2007 mass shooting at the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, in Blacksburg, Virginia, where 33 people were killed] he reloaded 17 times. My philosophy is – people can always do something. Guns are just a tool and they have weak spots, such as having to be reloaded. So, how can you interfere?”

Some people believe such training can he harmful, and even counterproductive.

Ken Trump, an outspoken critic of the so-called options-based training offered by Mr Crane and others, says there was widespread evidence lockdowns were the most effective way to react to a shooter. He said schools needed to diversify their drill training – to carry out tests at “difficult” times of day such as the lunch hour, rather than always 9.00am – but they were still the best response.

“The standard is – what is reasonable and what crosses the line of reasonableness,” said Mr Trump, a school safety expert from Ohio. He said self-evacuation of pupils could create a “target rich” environment for a shooter as well as a crowd to escape in, and that teachers trying to throw things at a shooter, were being asked to leave the safety of a locked classroom.

The Association of School Psychologists and the Association of School Safety Officials have said options-based training can be traumatic for children, and provides guidelines for schools. Meanwhile, The Atlantic has questioned the wisdom of any shooting drills as they are currently used.

“Studies of whether active-shooter drills actually prevent harm are all but impossible. Case studies are difficult to parse,” James Hamblin wrote after the shooting at Parkland.

“In Parkland, for example, the site of the recent shooting, Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, had an active-shooter drill just last month. The suspect had been through such drills, and may have used them to his advantage.”

Teachers and principals, who watch, horrified as each new school shooting makes news – Red Lake, Minnesota in 2005; Virginia Tech; Newtown, Connecticut in 2012; Santa Monica in 2013; Roseburg, Oregon, in 2015 or Parkland in February last year – worry they would be be next, the site of incident so grave it becomes known by a single word.

Dan Rambler, director of student services and safety in the Akron school district of Ohio, one of those that uses Mr Crane’s system, recently told Education Week, he was trying not to scare students, but also to prepare them. “That’s the fine balance,” said Mr Rambler. ”We’re not trying to panic people.“

Mr Crane had a blunt response to suggestions that his training upsets children: children were probably upset by being ordered to sit under their desk during Cold War nuclear drills, or by training about the potential danger of strangers.

And he said evidence suggested people could be taught to confront danger. He pointed to the example of United Airlines Flight 93, hijacked on 9/11 by al-Qaeda militants and crashed into a field in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, after passengers tried to storm the cockpit after learning of what had happened in New York and fearing their flight was also to be used to attack a target. “You look at airlines now. If a passenger gets out of line or gets drunk, he’s tied to his seat by other passengers.”

This week in Columbine, relatives of those who were killed, along with survivors, have been sharing their stories, lamenting how events there seemed to herald in a more dangerous era for the nation’s schoolchildren. Students, meanwhile, were ordered to go on lockdown after police issued an alert after a highly dangerous Florida teenager, “infatuated” with the 1999 shooting, was seen in the area. The 18-year-old was subsequently found dead.

Austin Eubanks, 37, who survived being shot in the school’s library 20 years ago, suffered trauma after watching one of his closest friends, Corey DePooter, killed. For a decade afterwards, he was addicted to prescription painkillers.

He now travels the country and tells his story about the pain, both collective and individual, that a shooting creates. He told the Associated Press he was frustrated little had been done to address the root causes of such incidents, while active-shooter drills and armed guards had become routine.

“We are so unwilling to actually make meaningful progress on eradicating the issue,” said Mr Eubanks. “So we’re just going to focus on teaching kids to hide better, regardless of the emotional impact that that bears on their life.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments