Climate bid faces tricky path over money for electric cars

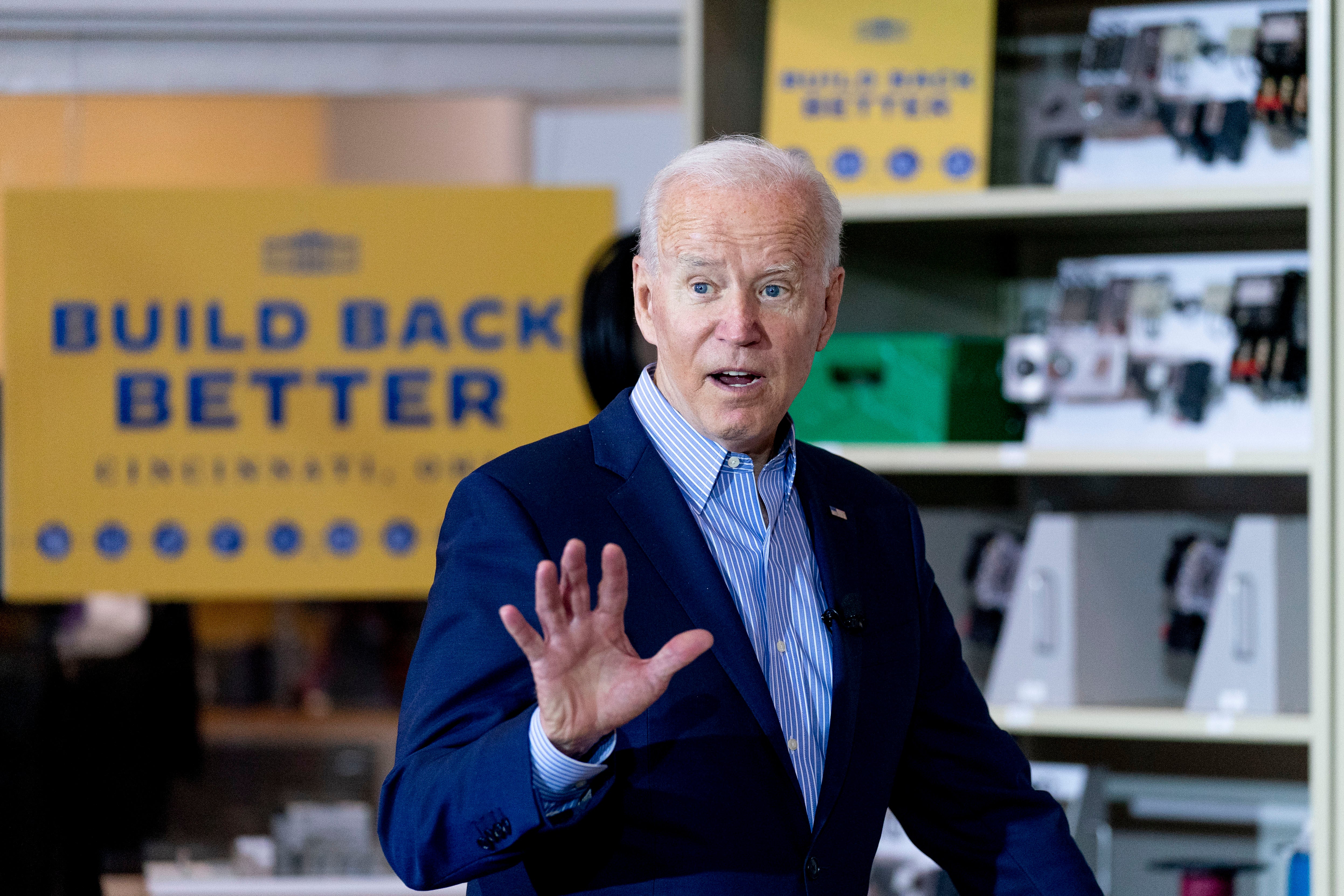

The bipartisan compromise on infrastructure cuts in half President Joe Biden’s call for $15 billion to build 500,000 electric vehicle charging outlets

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The bipartisan compromise on infrastructure cuts in half President Joe Biden’s call for $15 billion to build 500,000 electric vehicle charging outlets, raising the stakes as the administration seeks to win auto industry cooperation on anti-pollution rules to curb climate change.

The Senate legislation provides $7.5 billion in federal grants to build a national network of charging outlets, an amount that analysts say is a good start but isn't enough to spur widespread electric vehicle adoption.

Still, even the smaller amount can be effective if they're placed in the right locations, said Jessika Trancik, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who studies EV charging.

“If there’s half the funding, you have to be twice as strategic and twice as deliberate," she said.

Biden has made combating climate change a policy priority, and the broad compromise bill reached after intense negotiations takes some steps toward his goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions in half by 2030. Widespread availability of electric charging stations in communities big and small is the cornerstone of his efforts to switch America’s car and truck fleet from polluting combustion engines to zero-emissions electric. Many drivers are hesitant to make the switch for fear of running out of electricity with no charging station in sight.

The back-and-forth in a closely divided Congress over EV funding reflects a tricky balance for the auto industry and the Biden administration. The transportation sector is the single biggest U.S. contributor to climate change.

Currently there are just over 43,000 charging stations in the U.S. with more than 106,000 outlets, according to the Department of Energy. Fully electric vehicles last year represented just 2% of new vehicle sales in the U.S., or about 1.1 million vehicles on the road.

The Biden administration had planned to build a half-million charging units around the country to fulfill a campaign promise and nudge a significant number of Americans into zero-emission vehicles by 2030. It intended to tap an additional $7.5 billion in low-cost loans from an infrastructure bank of public-private investment that was to be created in the Senate bill.

But the president’s plans evaporated Wednesday after lawmakers haggling over wage laws for transportation projects covered by the $20 billion bank gave up and eliminated it. The White House now says it won't set a specific target for charging units but hopes to find other funding to cover the gap.

“The future of cars is electric, and we’re ready,” Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg tweeted Wednesday after the bipartisan deal was announced.

The Associated Press reported Tuesday that the Biden administration plans to issue proposed rules as early as next week on tailpipe emission standards, including nonbinding language that at least 40% of U.S. sales be electric vehicles, according to government and industry sources who spoke on condition on anonymity to reveal details that are still being finalized.

While Ford CEO Jim Farley announced Wednesday that he expects 40% of the company's sales to be fully electric vehicles by 2030, other companies are still weighing whether to endorse that figure. Stellantis, for instance, has has committed to a 40% U.S. sales figure, but counts “low-emission vehicles" such as gas-electric hybrids in its mix.

In the past year, U.S. automakers have accelerated announcements of new electric vehicles, spending billions to develop them. Some, including General Motors and Volvo, have set goals of selling only electric passenger vehicles by 2035.

But nearly all have said it will take government incentives to persuade people to switch to the new technology, at least until EV prices fall as more are produced and sold. And they have said that government spending on charging infrastructure is essential to overcoming consumer anxiety about running out of electricity.

Biden had originally proposed $174 billion in his Build Back Better plan to boost the EV market, including tax credits and other incentives to spur consumers to embrace the newer technology. While only $7.5 billion of that in the bipartisan bill will go to charging stations, Democrats are expected to add back roughly $100 billion in EV tax credits in a separate $3.5 trillion “reconciliation” bill. Support from all 50 Democratic senators will be needed for that bill to pass.

“If a reconciliation bill emerges with 10 digits of guaranteed EV rebate money, that will go a long way towards reassuring automakers that they can ramp up production,” said Jeff Davis, a senior fellow at Eno Center for Transportation.

Automakers have made it clear the government needs to help make the switch away from internal combustion engines.

“Much of this transition is going to depend on government support, infrastructure build-out,” Ford's Farley said during its second-quarter earnings conference call Wednesday.

According to a Consumer Reports survey last December, anxiety about limited range and the availability of charging stations were among the top concerns consumers had about owning an EV.

Currently electric vehicle owners charge their vehicles at home 80% of the time. But that is likely to change as more people buy EVs who don’t have a garage to house a charging station.

New chargers should be located based on models that predict where they will be needed, MIT's Trancik said. They should be placed along travel corridors for people going long distances, as well as in areas where people spend lots of time, such as hotels, apartment building parking lots and even along public streets, MIT's Trancik said. The government also will have to raise incentives to get charging stations built in less-populated rural areas, she said.

Direct current fast chargers, which can charge a car up to 80% of its battery capacity in 20 to 45 minutes, are quite expensive, costing $40,000 to $100,000. So those should be placed where people need to charge quickly and get back on the road.

Chargers that run on 240-volt electricity similar to what powers a clothes dryer are far cheaper, around $2,000. They take around eight hours to fully recharge a car. Trancik says they can be used effectively at much lower costs in areas where people stay for long periods of time.

___

Krisher reported from Detroit.