Five of ten siblings vanished in a Christmas Eve house fire. Were they taken?

When the West Virginia home of Italian immigrants caught fire on Christmas Eve 1945, the parents and four siblings got out. Five other young children were never found - and neither were their remains. What happened to the Sodder siblings? asks Sheila Flynn

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Sylvia Paxton died last year in West Virginia at the age of 79, her obituary read like the typical loving ode to a wonderful small-town woman - a matriarch whole-heartedly dedicated to family.

She was “unsurpassed as a wife and a mother” and had an “infectious laugh and a delightful sense of humor,” the obit read, adding that she’d been preceded in death by her husband, granddaughter, three brothers and a sister.

But then came a very odd line: “Five other siblings were unable to be located following a fire that occurred in December 1945 in their Fayetteville home: Maurice, Martha, Louis, Jennie, and Betty.”

“Unable to be located” - What did that mean, might wonder anyone from outside of West Virginia.

Anyone and everyone nearby would have already known, however.

Because Mrs Paxton, herself a mother of two and a grandmother at the time of her death, had survived that same 1945 fire as a baby, escaping with her parents and three other siblings in a case that would spark regional lore, intrigue, conspiracy theories and a highway billboard for decades.

No human remains were found after the fire at the home, which belonged to Italian immigrants George Sodder, born Giorgio Soddu in Sardinia, and his wife, Jennie. Sightings began popping up all over the country of the five missing children – as did people claiming to be the vanished siblings.

Jennie Sodder wore black for the rest of her life – marking a mourning custom from her native Italy that was almost entirely uncommon in West Virginia.

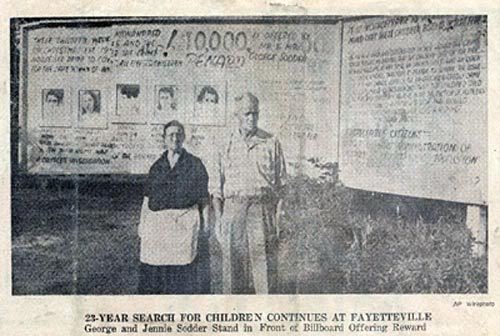

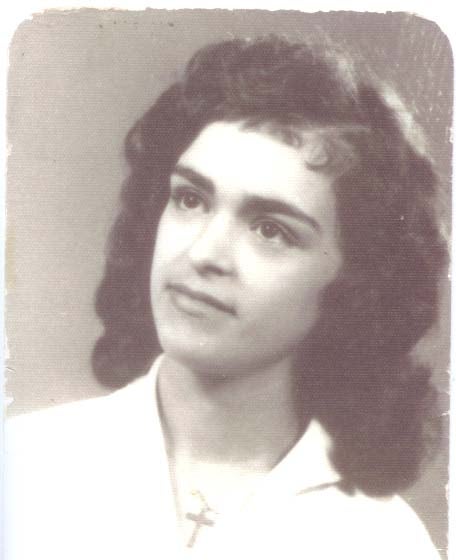

She and her husband erected a billboard nearby along the highway that detailed the strange case, featured pictures of the five missing kids and offered thousands of dollars in reward money for information about what happened to the Sodder siblings.

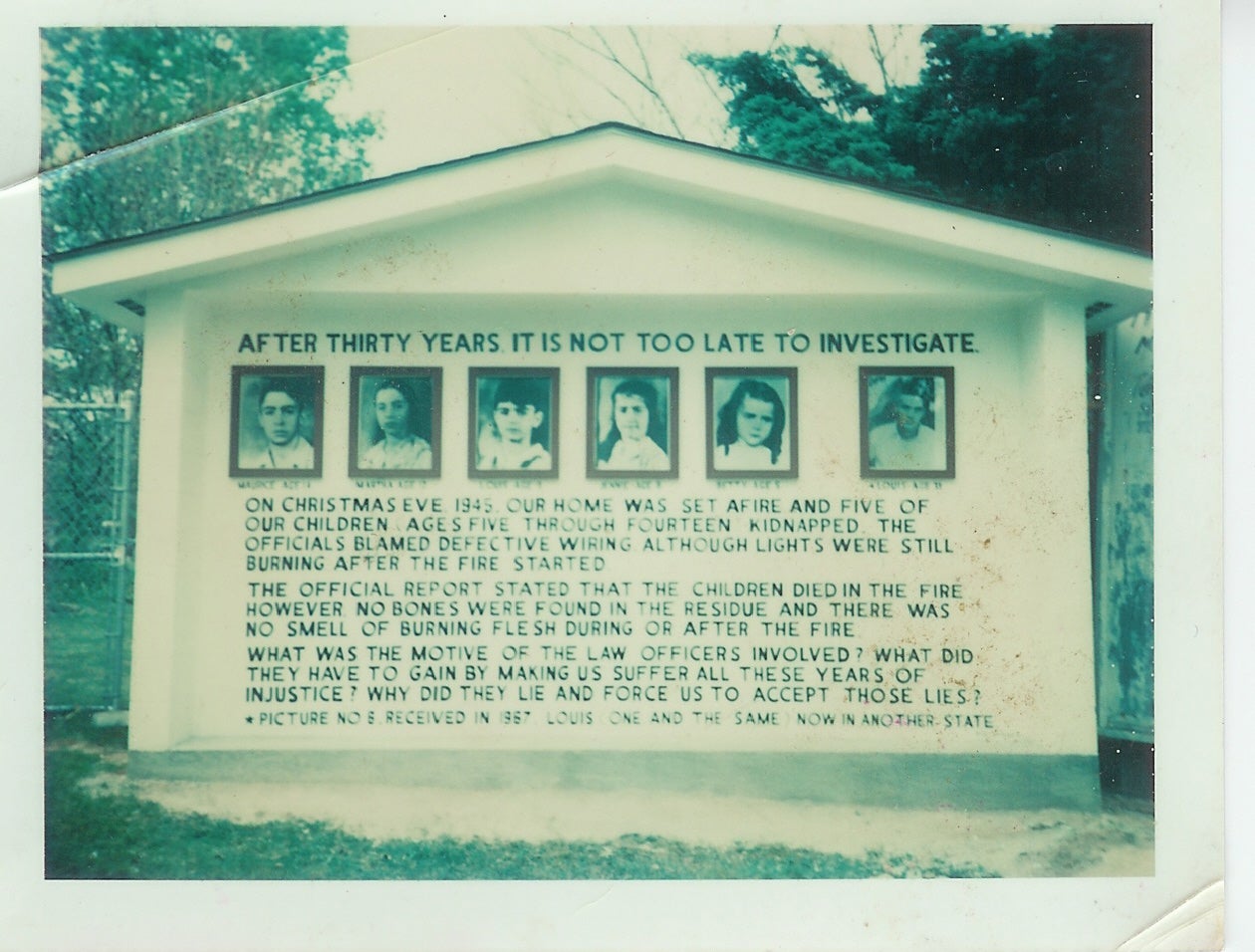

They updated the billboard as the years progressed, with the final one reading: “After thirty years, it is not too late to investigate.”

The youngest of the children, Sylvia - who escaped the blaze as a baby with her parents - believed wholeheartedly until her death last year that her siblings hadn’t died on that ill-fated Christmas Eve, her daughter tells The Independent. The baby of the family’s memories were scant of her older brothers and sisters, but her own children grew up in the shadow of a tragic mystery that, for years, didn’t even seem strange when discussed in relatives’ households.

“It was part of our family growing up,” Jennie Henthorn, 53, tells The Independent. “It wasn’t something that my brother and I realized was abnormal, because it was just always there.

“We’d go visit my grandmother at least once a week; we went usually on Sunday, and we drove in past the billboard every single time. It didn’t occur to us that that was something that was unusual or unique to our family.”

Ms Henthorn, who runs an environmental services firm, doesn’t really remember her grandfather, who died when she was two years old. She does, however, remember the clan’s black-clad matriarch.

“When the whole family was together, my grandmother didn’t talk about it as much,” she says. “When it was just my mom, it was on [her grandmother’s] mind, she talked about it a lot.”

She adds that her grandmother, Jennie, “was always in mourning, even more so after my grandfather died, from what my mom told me”.

“I think that it was something they dealt with together before he died, and then, once my grandfather died, I think more of my grandmother’s discussion passed onto my mom instead of her husband. And my grandmother and my mom were really, really close – because, you know, she was with them” on the night.

“She was the only child in a lot of ways,” Ms Henthorn tells The Independent. “You’ve got to think that my aunts and uncles that were present after the fire, who were still at home, weren’t really at home. Two had been away at the war. They were grown.”

It was certainly a circuitous route that had brought the Italian family to West Virginia and united nine of the ten children under the Sodder roof on Christmas Eve 1945. And that route only raised further questions after the fire.

Mr Sodder emigrated from Italy with an older sibling and worked on the railroads; while his big brother opted to return to Europe because he was “homesick,” Ms Henthorn says, ”my grandfather stayed - and he was a just a boy.”

He worked on the railroads in Pennsylvania - “not directly, but they would allow him to carry supplies and do things, liked that,” she tells The Independent. Then he became a driver, returned to cities to taxis, and then “came to West Virginia,” she says.

“He realises people need goods from the railroads to their houses, so that’s actually how he started,” Ms Henthorn says, describing her grandfather like a modern-day Amazon. “He had a trucking business here, but it wasn’t associated with mining; it was picking up things at the railroad and delivering it to people.

“Then he realised he could truck coal - and he starts trucking coal, and then he had a few coal mines of his own,” in West Virginia, where there were pockets of Italian immigrants and still are, she says. “He didn’t like the mining; he lost a guy and it broke his heart ... [It was the] first time that somebody’d worked for him that died, and that was it. He sold his mines and he went back to the trucking.”

He was back working in trucking on Christmas Eve 1945 when a fire broke out at the proud family’s two-story house on the outskirts of Fayetteville. At home were nine of the family’s ten children; the tenth son was off serving with the military.

Around 1 a.m., according to reports, a deadly fire broke out and swept through the home as 11 family members slept.

Awaking in the downstairs bedroom he shared with his wife and baby, Sylvia, Mr Sodder got them out and raced to rescue the rest of the children, attempting to break a “window to re-enter the house, slicing a swath of skin from his arm,” Smithsonian Magazine reported ten years ago.

“He could see nothing through the smoke and fire, which had swept through all of the downstairs rooms: living and dining room, kitchen, office, and his and Jennie’s bedroom. He took frantic stock of what he knew: 2-year-old Sylvia, whose crib was in their bedroom, was safe outside, as was 17-year-old Marion and two sons, 23-year-old John and 16-year-old George Jr., who had fled the upstairs bedroom they shared, singeing their hair on the way out.

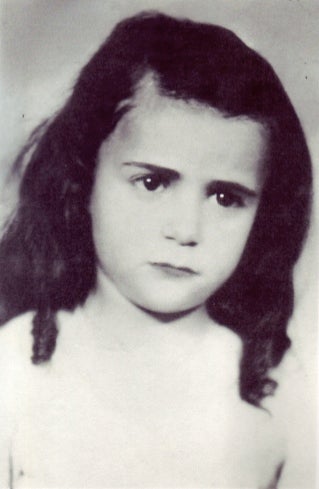

“He figured Maurice, Martha, Louis, Jennie and Betty still had to be up there, cowering in two bedrooms on either end of the hallway, separated by a staircase that was now engulfed in flames.

“He raced back outside, hoping to reach them through the upstairs windows, but the ladder he always kept propped against the house was strangely missing. An idea struck: He would drive one of his two coal trucks up to the house and climb atop it to reach the windows. But even though they’d functioned perfectly the day before, neither would start now. He ransacked his mind for another option. He tried to scoop water from a rain barrel but found it frozen solid. Five of his children were stuck somewhere inside those great, whipping ropes of smoke. He didn’t notice that his arm was slick with blood, that his voice hurt from screaming their names.”

According to the magazine, teenage Marion not only tried to get help from a neighbour’s home but another witness called authorities from a nearby tavern. When there was no response from operators, the witness drove into Fayetteville to find the fire chief, who eventually “initiated Fayetteville’s version of a fire alarm: a “phone tree” system whereby one firefighter phoned another, who phoned another,” the magazine reported.

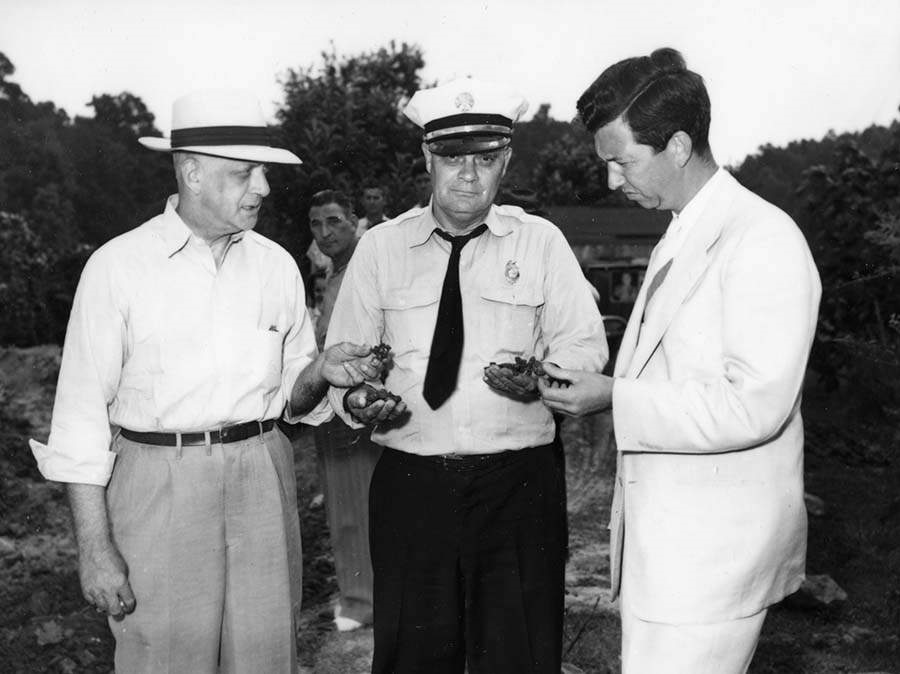

“The fire department was only two and a half miles away but the crew didn’t arrive until 8 a.m., by which point the Sodders’ home had been reduced to a smoking pile of ash.”

That’s also when the Sodders initially suspected five of their children - the girls and boys in between their young adult son and baby daughter - had perished. George and Jennie took solace in their surviving children, whose ages spanned more than two decades.

That solace didn’t last long, though. Too many questions lingered.

Not least was the discovery of no human remains at the fire site; even the hottest fire - which investigators didn’t think the Sodder blaze merited - would have presumably left some bones, tissue or other clues to identify victims, they theorised. And then came the spottings of the missing children.

Two witnesses at separate locations in South Carolina, soon after the fire, told authorities they’d seen the five siblings.

“The children were accompanied by two women and two men, all of Italian extraction,” a Charleston hotel worker told police, according to Smithsonian. “I do not remember the exact date. However, the entire party did register at the hotel and stayed in a large room with several beds.

“They registered about midnight. I tried to talk to the children in a friendly manner, but the men appeared hostile and refused to allow me to talk to these children…. One of the men looked at me in a hostile manner; he turned around and began talking rapidly in Italian. Immediately, the whole party stopped talking to me. I sensed that I was being frozen out and so I said nothing more. They left early the next morning.”

Ms Henthorn, despite the slew of communications received by her family, says Charleston accounts were the most meritorious in her family’s eyes amidst a cascade of contact from presumed fraudsters, investigators, clairvoyants and people who claimed to be her relatives.

She says her family believed a woman who said she’d seen the children in the company of people of Italian descent in Charleston right after the fire - a woman who said the encounter made her uncomfortable.

“The kids were not allowed to talk,” Ms Henthorn tells The Independent of the witness story her family believed, adding: “The adults did all the talking, and it was an uncomfortable situation .... she could feel the discomfort.

“My grandpa really placed a lot of credence in that.

She adds: “Everybody theorised, but nobody knew there were no clear leads on that.”

Those theories ran the gamut. Some, tracing the family’s Italian ancestry, hypothesized the mafia’d been involved. Others noted Mr Sodder’s outspokenness; he was a vocal critic of Mussolini. Other theories were more far-fetched and sometimes even localised.

“George held strong opinions about everything from business to current events and politics, but was, for some reason, reticent to talk about his youth,” the Smithsonian reported. “He never explained what had happened back in Italy to make him want to leave.”

On top of that, the magazine wrote, family members had noted unusual occurrences in the run-up to the fire.

“There was a stranger who appeared at the home a few months earlier, back in the fall, asking about hauling work. He meandered to the back of the house, pointed to two separate fuse boxes, and said, ‘This is going to cause a fire someday.’

“Strange, George thought, especially since he had just had the wiring checked by the local power company, which pronounced it in fine condition,” the magazine reported. “Around the same time, another man tried to sell the family life insurance and became irate when George declined.

“‘Your goddamn house is going up in smoke,’ he warned, “and your children are going to be destroyed. You are going to be paid for the dirty remarks you have been making about Mussolini.” George was indeed outspoken about his dislike for the Italian dictator, occasionally engaging in heated arguments with other members of Fayetteville’s Italian community, and at the time didn’t take the man’s threats seriously.

“The older Sodder sons also recalled something peculiar: Just before Christmas, they noticed a man parked along U.S. Highway 21, intently watching the younger kids as they came home from school.”

Ms Henthorn doesn’t really have her own theory about what happened to her aunts and uncles - but she firmly feels that they survived.

“Do I believe that they perished in the fire that night? I do not,” she tells The Independent, though she says she doesn’t find herself scanning crowds for people who could be related to her. Given the siblings’ ages, she also believes that, even if they enjoyed lives elsewhere after the fire, they’ve probably passed away at this point.

“I don’t think they’re here,” she says. “If they are still here, I don’t think they’re in West Virginia.”

For decades, the family financed a billboard not far from their house, a desperate plea for people to come forward that featured pictures of the missing children. It attracted its share of well-wishers, conmen and lonely people simply look to make a connection - and the Sodder family declined to dismiss the most vulnerable, according to Ms Henthorn.

Part of that was hope; part was a testament to their character, she says.

“Right before my grandfather died, my dad took him to Texas to follow up on a lead,” Ms Henthorn said. “He was very sick, and my dad drove him the whole way to Texas - and he was so disappointed that it didn’t pan out that they literally turned around and drove back.

“I don’t know how my dad did it,” she says of the drive, which would have taken a minimum of 14 hours.

The West Virginia billboard only came down in 1989, after Jennie Sodder’s death.

Despite the family’s belief that the children survived, however, she says “My mom was the youngest of the children, and she’s now passed - so, realistically, any possibility of finding out what happened is gone. I really do believe that.”

She adds that she and her brother “have no desire to find anyone who doesn’t want to be found.

“Anybody who knew what happened would’ve been my grandparents’ age,” she continues. “I would think that ... it’s been public enough that, if the children wanted to be found later on in life, then they would’ve reached out.

“We would like for the story to still survive, just because, if nothing else, it’s a beautiful love story.

“My grandparents loved those children so much that they never gave up hope of finding them,” she says, adding: “It’s something that I think resonates with people, because it wasn’t a single child. It was such a large part of the family, and it was at such a tragic time - Christmas.”

The case, she says, “resonates on our deepest fears.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments