Campaign to end tipping and pay waiting staff a living wage gathers pace

Campaigners say tipping results in poverty and sexual harassment

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There is a deftness about the waiters and waitresses that do their thing at the rather fashionable New York restaurant Dirt Candy.

Friendly but not fawning, efficient but not overbearing. Professional. And that could well be the result of them being paid $25 an hour, as opposed to the legal minimum of just $2.13.

The vegetarian eatery is among a growing wave of restaurants in the country that have taken a decision to pay waiting staff a living wage, rather than making them rely on tips. Critics of tipping hope it will end a system they say is unfair and outdated, and results in poverty and sexual harassment.

“I really don’t agree with the tipping system, it does not work. There are all sorts of inherent problems,” Amanda Cohen, the chef and owner of Dirt Candy, told The Independent.

“It means we’re outsourcing our human resources policy to my customers. If I have a bad day, or if no-one comes to the restaurant because it’s a blizzard but I’ve asked the staff to come in, then why should they suffer?”

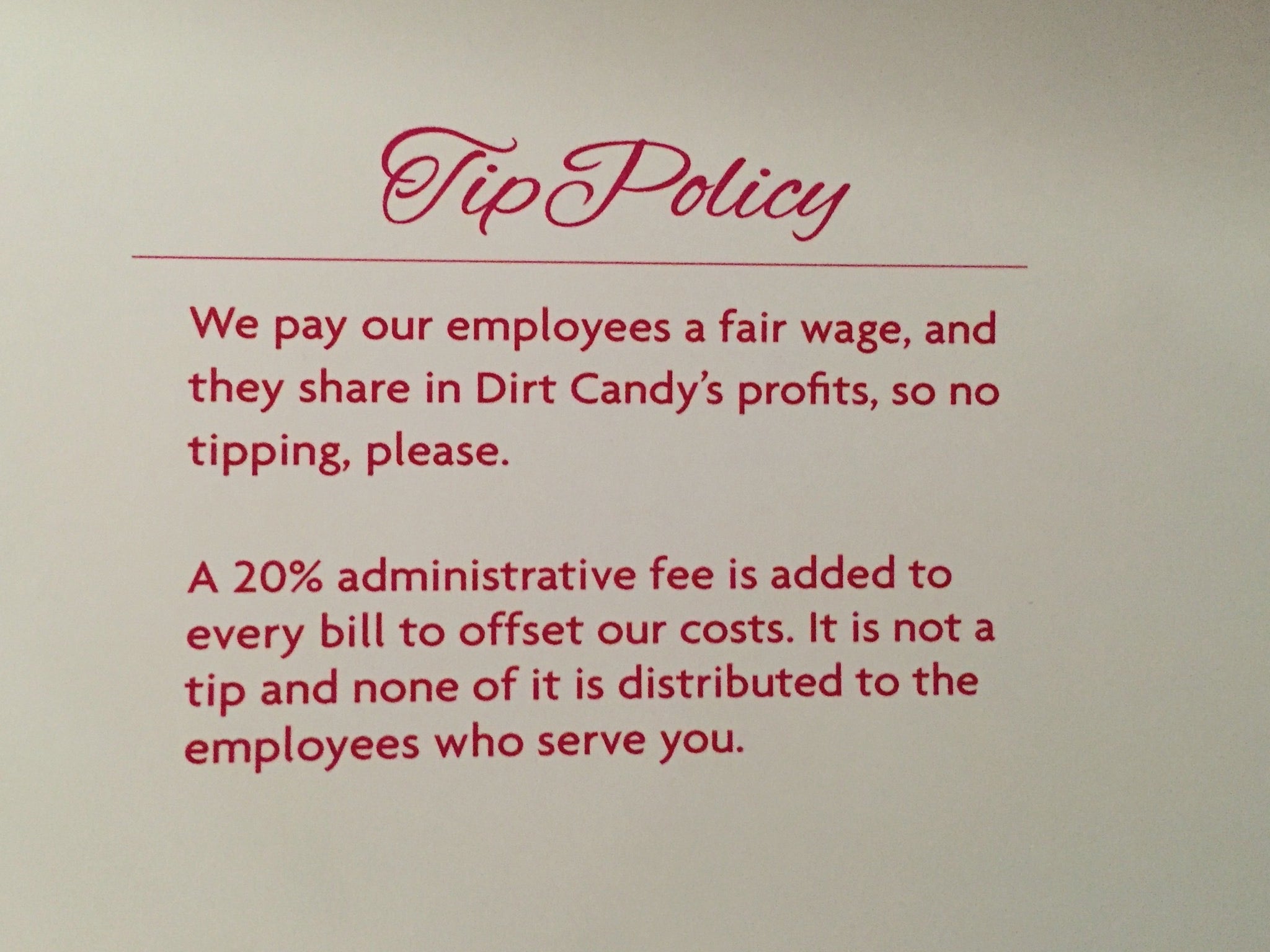

Ms Cohen’s business model involves attaching a 20 per cent “administrative fee” to every bill, but does not leave a space on the receipt for a customer to add a tip. (She said customers can leave a tip if they want to reward exceptional service, but that it is not a requirement.)

“I think it’s better,” said one Dirty Candy waitress. “I just moved to the New York from the west coast and a lot of restaurants there are doing this.”

The New York Times reported last month that Ivar’s seafood restaurants in Seattle had also raised prices 21 per cent and ended tipping, allowing the company to increase wages.

“We saw there was a fundamental inequity in our restaurants where the people who worked in the kitchen were paid about half as much as the people who worked with customers in front of the house,” said co-owner Bob Donegan.

Maria Myotte of the union Restaurant Opportunities Centres United, said under the law, restaurants were not obliged to pay waiting staff who received tips more than $2.13 an hour, a figure that had not increased since 1991 and which was kept low by lobbying from the corporate restaurant industry. Her union supports the move away from tips and towards fair wages.

She said research revealed half of restaurant workers lived in poverty and were twice as likely to be using food stamps as other workers. She said 70 per cent of waiting staff were women and that 90 per cent of waitresses who depended on tips had reported sexual harassment, a situation created by the need to appear ‘flirtatious’.

“Restaurants should adopt a business model that means employers pay a fair wage,” she said.

The alternative to proper wages, say campaigners, are the kinds of stories like that of New Jersey student Jessica Corrine who works at a restaurant to pay for college and who gets a base of $2.50 an hour.

Last month, when – through no fault of her own – a group of diners was kept waiting an hour, they declined to pay a tip. Instead they wrote LOL – “laughing out loud” – on the receipt.

“Most of my pay-checks are less than pocket change because I have to pay taxes on the tips I make. I need tips to pay my bills. All waiters do,” Ms Corrine wrote on a Facebook post that went viral.

At Dirt Candy, Ms Cohen has created quite a buzz with her innovative, sharing-sized fare.

Of the four plates ordered by the The Independent, two scored very highly, the other two less so. The staff were all impeccable.

Outside, the diners leaving were impressed both by Ms Cohen’s food and her decision to pay her staff. Four members of the Sydney family from Dallas, said they had noticed little difference to their own bill, given that most people usually tipped around 20 per cent anyway.

One of them said: “They are paying their staff properly.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments