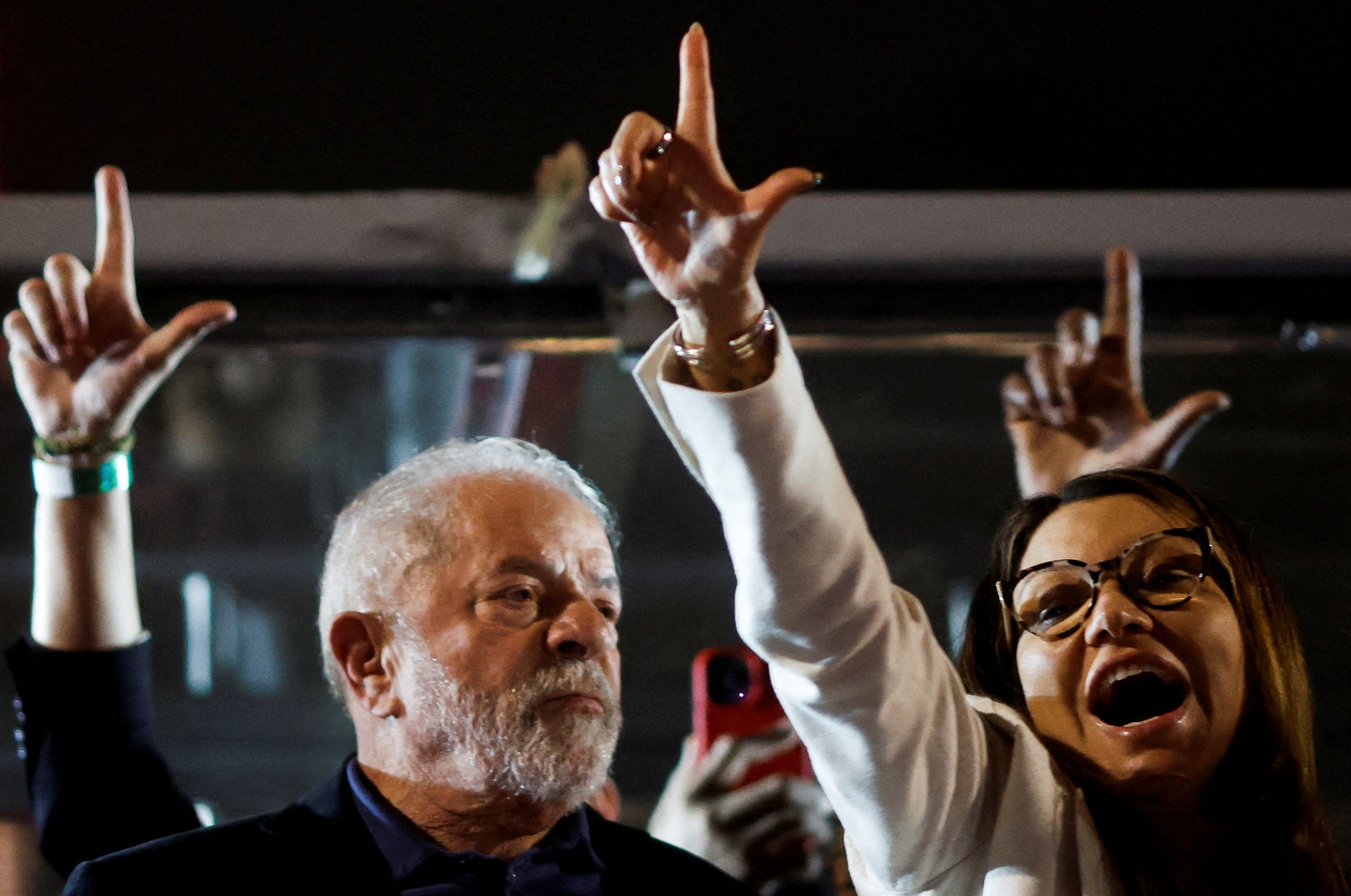

Bolsonaro and Lula face Brazil presidential run-off after close first vote

Final round to take place on 30 October as experts predict an ‘ugly’ election race

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Brazil presidential election will go to a second round of voting after a surprisingly close initial vote between Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva and his populist rival Jair Bolsonaro.

With almost all votes counted, Mr Da Silva, commonly known as Lula, received 48 per cent, while incumbent Mr Bolsonaro got 43 per cent.

The vote was much closer than predicted, and shows that Brazil is even more politically polarised between left and right thasn previously thought. Prior to the election, speculation centered on whether or not Lula would take 50 per cent of the vote to claim the presidency first time round.

The last pre-election poll published on Saturday gave Lula 50 per cent of the votes, well ahead of Bolsonaro. The difference between the pair in the first round amounted to around six million votes.

Both sides can claim victory ahead of campaigning for the second round run-off which takes place on 30 October.

Lula is ahead in the polls and on the verge of a stunning political comeback, as he was in jail at the time of the last presidential election. Bolsonaro, who had threatened not to recognise the result if he lost, had long claimed the vote would be closer than polls suggested.

Speaking at a post-vote press conference, Mr Da Silva, a big football fan, described the upcoming run-off as “extra-time”.

“I want to win every election in the first round. But it isn’t always possible,” he said.

Mr Bolsonaro said he understood there was “a desire for change” among the population battered by an economic crisis and high inflation, adding “but certain changes can be for the worse”.

Although the vote was virtually free from the widespread political violence many had feared, a second-round vote could add to the fierce polarisation and simmering political tensions in Brazil.

Alexandre de Moraes, the Supreme Court justice who also leads the electoral authority, congratulated Brazil for the “safe, calm, harmonious and peaceful” election that demonstrated its democratic maturity.

Yet tensions remain high. The election will determine whether the country returns a left-winger to the helm of the world’s fourth-largest democracy or keeps the incendiary Bolsonaro in office for another term.

There were nine other candidates, but the election was always going to be about a straight duel between two extremes, represented by Lula and Bolsonaro.

“This is a big defeat for the democratic centre that saw its voters migrate to Bolsonaro in a polarised scenario,” said Arilton Freres, director of Curitiba-based Instituto Opiniao. “Lula starts ahead, but it won’t be easy for him.”

The past four years under Bolsonaro have been marked by severe strains being placed upon the country’s democratic institutions, criticism of his government’s response to the Covid pandemic and the worst deforestation of the Amazon rainforest in 15 years.

A slow economic recovery has yet to reach the poor, with nearly 33 million Brazilians going hungry despite higher welfare payments.

But Bolsonaro has built a devoted base by defending conservative values and presenting himself as protecting the nation from left-wing policies that he says infringe on personal liberties and produce economic turmoil.

Lula, who was president from 2003 to 2010, was jailed during the last election in 2018 and was unable to run against Mr Bolsonaro. He was banned from running over a corruption and money laundering conviction, for which he was sentenced to 12 years in prison.

He served 19 months before the conviction was annulled by the Supreme Court on the grounds that the judge colluded with prosecutors – a move that had allowed to face his rival this year.

Bolsonaro outperformed in Brazil‘s southeast region, which includes the highly populous Sao Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais states, according to Rafael Cortez, who oversees political risk at consultancy Tendencias Consultoria.

“The polls didn’t capture that growth,” he said. “It leaves a bitter taste for the left, if we consider what the polls were showing.”

Political economist Filipe Campante said: “Make no mistake about it, the odds look substantially bleaker for Brazilian democracy right now than they did 24 hours ago. Bolsonaro will have a real shot at winning the run-off, and in that case we are in deep trouble.”

Carlos Melo, a political science professor at Insper University in Sao Paulo, said: “It is too soon to go too deep, but this election shows Bolsonaro’s victory in 2018 was not a hiccup.”

Speaking after the results, da Silva betrayed the fact he didn’t know which date the run-off was taking place, but he said he was excited at the opportunity to go face-to-face with Bolsonaro.

“During this whole campaign, we were ahead in the opinion polls of all the institutes, even those that didn’t want us to win,” da Silva said. “I always thought that we were going to win these elections. And I tell you that we are going to win this election.”

The right’s positive night extended to races for governorships and congressional seats, especially candidates with Bolsonaro’s blessing.

His former infrastructure minister surprised by finishing first in the race to govern Sao Paulo. The governor of Rio de Janeiro, an ally, vanquished his opponent to win reelection outright. Sergio Moro, the former judge who temporarily jailed da Silva and was Bolsonaro former justice minister, defied polls to win a Senate seat.

Bolsonaro’s Liberal Party will surpass da Silva’s Workers’ Party to become the biggest in the Senate. In the Lower House, Bolsonaro’s Liberal Party and the coalition led by da Silva’s Workers’ Party will be the chamber’s two largest forces.

“Brazil is much more polarised than many people thought, and governing will be difficult for whomever wins,” said Brian Winter, at the Americas Society/Council of the Americas.

“I think the next few weeks will put heavy strain on Brazil‘s democracy as these two men fight it out. Expect an ugly race that will leave scars.”

Additional reporting by agencies

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments