Barack Obama and Afghanistan: The inside story of a war the President never wanted

A new book by former US Defence Secretary Robert Gates is a damning indictment the war. The Watergate reporter Bob Woodward reveals the highlights of an explosive tome

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In a new memoir, former defence secretary Robert Gates unleashes harsh judgments about President Barack Obama’s leadership and his commitment to the Afghanistan war, writing that by early 2010 he had concluded the president “doesn’t believe in his own strategy and doesn’t consider the war to be his. For him, it’s all about getting out”.

Levelling one of the more serious charges that a Defence Secretary could make against a commander-in-chief sending forces into combat, Gates asserts that Obama had more than doubts about the course he had charted in Afghanistan. The president was “sceptical if not outright convinced it would fail,” Mr Gates writes in Duty: Memoirs of a Secretary at War.

Mr Obama, after months of contentious discussion with Mr Gates and other top advisers, deployed 30,000 more troops in a final push to stabilise Afghanistan before a phased withdrawal beginning in mid-2011.

“I never doubted Obama’s support for the troops, only his support for their mission,” Mr Gates writes.

As a candidate, Obama had made plain his opposition to the 2003 Iraq invasion while embracing the Afghanistan war as a necessary response to the 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States, requiring even more military resources to succeed. In Mr Gates’ highly emotional account, Obama remains uncomfortable with the inherited wars and distrustful of the military that is providing him options. Their different world views produced a rift that, at least for Mr Gates, became personally wounding and impossible to repair.

It is rare for a former US cabinet members, let alone a Defence Secretary occupying a central position in the chain of command, to publish such an antagonistic portrait of a sitting president.

Mr Gates’s severe criticism is even more surprising – some might say contradictory – because toward the end of Duty, he says of Obama’s chief Afghanistan policies: “I believe Obama was right in each of these decisions.” That particular view is not a universal one; like much of the debate about the best path to take in Afghanistan, there is disagreement on how well the surge strategy worked, including among military officials.

The sometimes bitter tone in the 594-page account contrasts sharply with the even-tempered image that he cultivated during his many years of government service, including stints at the CIA and National Security Council. That image endured through his nearly five years in the Pentagon’s top job, beginning in President George W Bush’s second term and continuing after Obama asked him to remain in the post. In the book, Mr Gates describes his outwardly calm demeanour as a façade.

Underneath, he writes, he was frequently “seething” and “running out of patience on multiple fronts”.

Mr Gates writes about Obama with an ambivalence that he does not resolve, praising him as “a man of personal integrity” even as he faults his leadership. Though the book simmers with disappointment in Obama, it reflects outright contempt for Vice President Joe Biden and many of Obama’s top aides.

Mr Biden is accused of “poisoning the well” against the military leadership. Thomas Donilon, initially Obama’s deputy national security adviser, and then-Lt. Gen. Douglas Lute, the White House coordinator for the wars, are described as regularly engaged in “aggressive, suspicious and sometimes condescending and insulting questioning of our military leaders”.

Mr Gates is 70, nearly 20 years older than Obama. He has worked for every president going back to Richard Nixon, with the exception of Bill Clinton. Throughout his government career, he was known for his bipartisan detachment, the consummate team player.

Duty is likely to provide ammunition for those who believe it is risky for a president to fill such a key Cabinet post with a holdover from the opposition party.

He writes: “I have tried to be fair in describing actions and motivations of others.”

He seems well aware that Obama and his aides will not see it that way.

While serving as Defence Secretary, Mr Gates gave Obama high marks, saying privately in the summer of 2010 that the president is “very thoughtful and analytical, but he is also quite decisive”. He added: “I think we have a similar approach to dealing with national security issues.” But in his book Mr Gates complains repeatedly that confidence and trust was what he felt was lacking in his dealings with Obama and his team.

“Why did I feel I was constantly at war with everybody, as I have detailed in these pages?” he writes. “Why was I so often angry? Why did I so dislike being back in government and in Washington?”

His answer is that “the broad dysfunction in Washington wore me down, especially as I tried to maintain a public posture of nonpartisan calm, reason and conciliation”.

His lament about Washington was not the only factor contributing to his unhappiness. Gates also writes of the toll taken by the difficulty of overseeing wars against terrorism and insurgencies in countries such as Iraq and Afghanistan. Such wars do not end with a clear surrender. Mr Gates acknowledges having ambiguous feelings about both conflicts. For example, he writes that he does not know what he would have recommended if he had been asked his opinion on Mr Bush’s 2003 decision to invade Iraq.

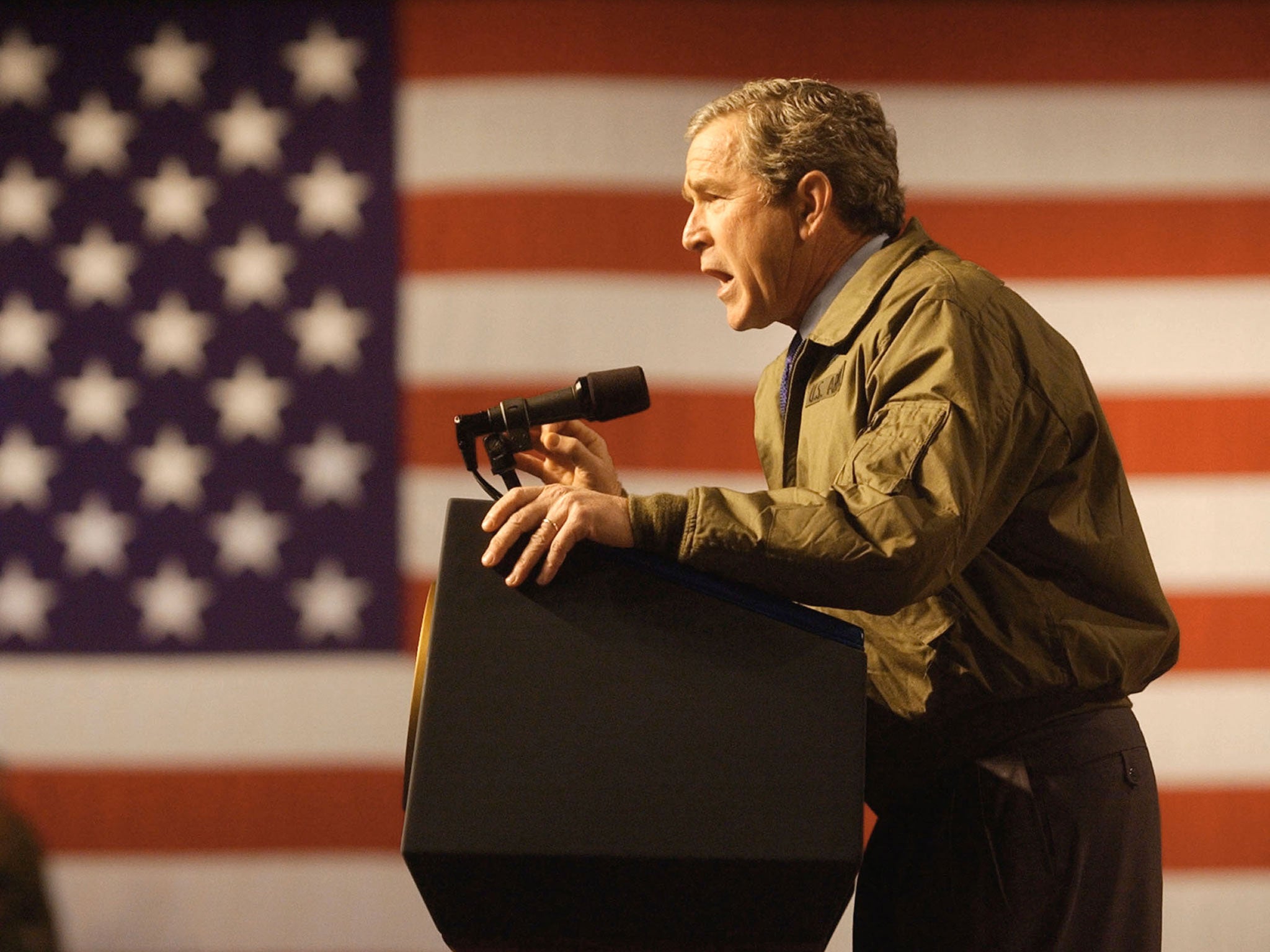

Three years later, Mr Bush recruited Mr Gates – who had served his father for 15 months as CIA director in the early 1990s – to take on the defence job. The first half of “Duty” covers those final two years in the Bush administration. Mr Gates reveals some disagreements from that period, but none as fundamental or as personal as those he describes with Obama and his aides in the book’s second half.

“All too early in the [Obama] administration,” he writes, “suspicion and distrust of senior military officers by senior White House officials – including the president and vice president – became a big problem for me as I tried to manage the relationship between the commander in chief and his military leaders”.

Mr Gates offers a catalogue of various meetings, based in part on notes that he and his aides made at the time, including an exchange between Obama and then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton that he calls “remarkable”. He writes: “Hillary told the president that her opposition to the [2007] surge in Iraq had been political because she was facing him in the Iowa primary...

“The president conceded vaguely that opposition to the Iraq surge had been political. To hear the two of them making these admissions, and in front of me, was as surprising as it was dismaying.”

Duty reflects the memoir genre, declaring that this is how the writer saw it, warts and all, including his own. That focus tends to give short shrift to the fuller, established record. For example, in recounting the difficult discussions that led to the Afghan surge strategy in 2009, Gates makes no reference to the six-page “terms sheet” that Obama drafted at the end, laying out the rationale for the surge and withdrawal timetable. Obama asked everyone involved to sign on, signalling agreement. According to the meeting notes of another participant, Mr Gates is quoted as telling Obama: “You sound the bugle... Mr President, and Mike [Mullen, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff] and I will be the first to charge the hill.”

Mr Gates does not include such a moment in Duty. He picks up the story a bit later, after David Petraeus, then the central commander in charge of both the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, made remarks to the press suggesting he was not comfortable with setting a fixed date to start withdrawal.

At a 3 March 2010, National Security Council meeting, Mr Gates writes, the president opened with a “blast”. Obama criticised the military for “popping off in the press” and said he would push back hard against any delay in beginning the withdrawal.

According to Mr Gates, Obama concluded: “If I believe I am being gamed...” and left the sentence hanging there with the clear implication the consequences would be dire.

Mr Gates continues: “As I sat there, I thought: the president doesn’t trust his commander, can’t stand [Afghanistan President Hamid] Karzai, doesn’t believe in his own strategy and doesn’t consider the war to be his. For him, it’s all about getting out.”

His second year with Mr Obama proved as tough. “For me, 2010 was a year of continued conflict and a couple of important White House breaches of faith,” he writes. The first, he says, was Obama’s decision to seek the repeal of the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy toward gays in the military.

Though Mr Gates says he supported the decision, there had been months and months of debate, with details still to work out.

On one day’s notice, Obama informed Mr Gates and Mr Mullen that he would announce his request for a repeal of the law. Obama had “blindsided Admiral Mullen and me”, Mr Gates writes.

Similarly, in a battle over defence spending: “I was extremely angry with President Obama,” Mr Gates writes. “I felt he had breached faith with me... on the budget numbers.” As with “don’t ask, don’t tell”, “I felt that agreements with the Obama White House were good for only as long as they were politically convenient.”

Mr Gates acknowledges forthrightly that he did not reveal his dismay. “I never confronted Obama directly over what I (as well as [Hillary] Clinton, [then-CIA Director Leon] Panetta, and others) saw as the president’s determination that the White House tightly control every aspect of national security policy and even operations. His White House was by far the most centralised and controlling in national security of any I had seen since Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger ruled the roost.”

It got so bad during internal debates over whether to intervene in Libya in 2011 that Mr Gates says he felt compelled to deliver a “rant” because the White House staff was “talking about military options with the president without defence being involved”.

Mr Gates says his instructions to the Pentagon were: “Don’t give the White House staff and [national security staff] too much information on the military options. They don’t understand it, and ‘experts’ like Samantha Power will decide when we should move militarily.” Ms Power, then on the national security staff and now US ambassador to the United Nations, has been a strong advocate for humanitarian intervention.

Mr Gates wanted to quit at the end of 2010 but agreed to stay at Obama’s urging, finally leaving in mid-2011. He later joined a consulting firm with two of George W Bush’s closest foreign policy advisers — former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and Stephen Hadley, the national security adviser during Mr Bush’s second term. The firm is called RiceHadleyGates. In October, he became president-elect of the Boy Scouts of America.

Mr Gates writes: “I did not enjoy being Secretary of Defence,” or as he emailed one friend while still serving: “People have no idea how much I detest this job.”

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments