Apple may end up in Supreme Court after defying US government order to hack into iPhone of San Bernardino shooter

Apple argues that it was essentially being asked to build a special 'back door' into the smartphone

In a legal collision that goes to the heart of the privacy-versus-national security debate, Apple, the computer and cellphone behemoth, said it was refusing to comply with a court order that it help investigators of the San Bernardino rampage to crack the code of an iPhone used by one of the shooters.

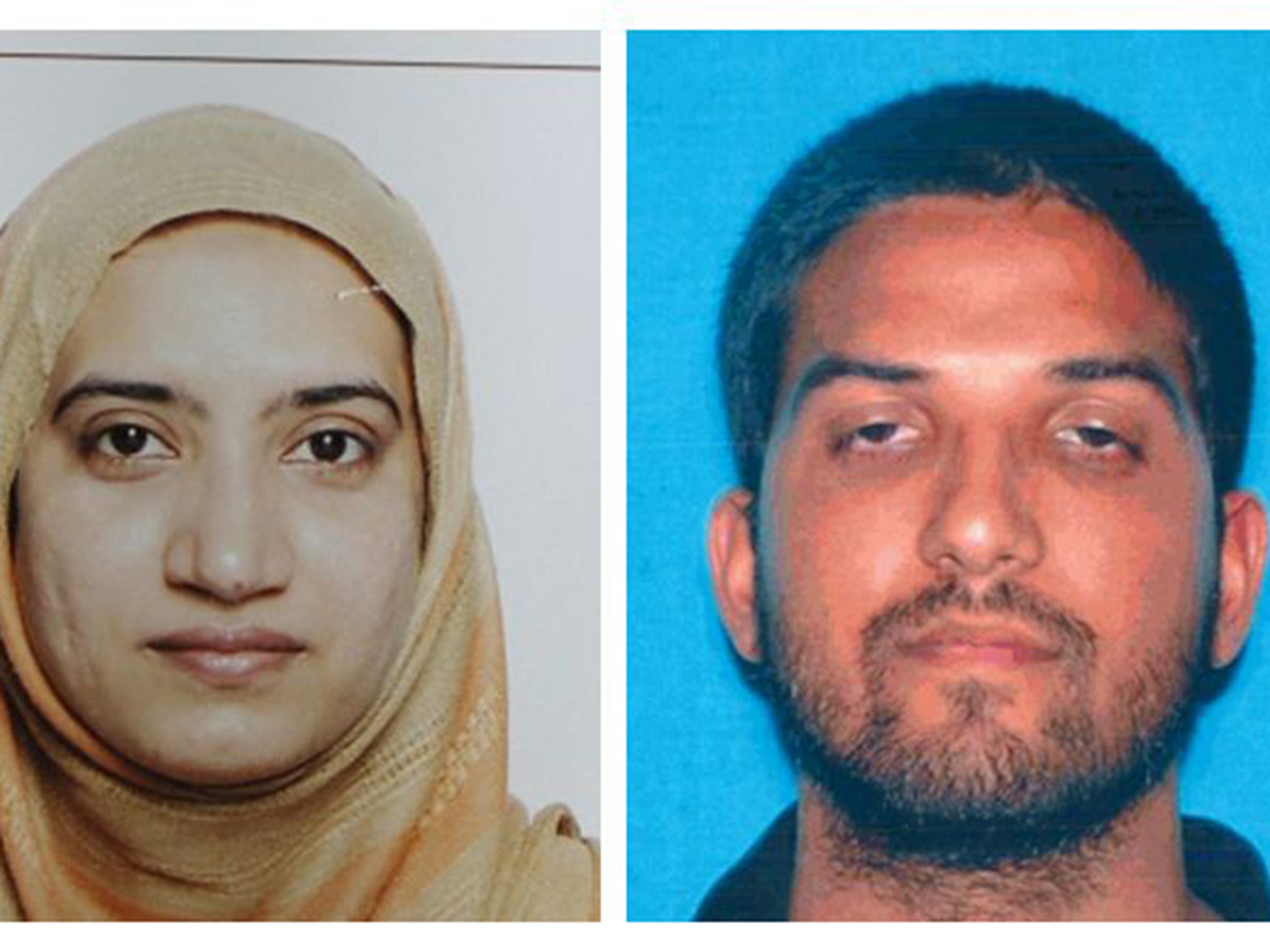

Furious that the California-based company would not assist the FBI in accessing data contained in an iPhone 5C that was in the hands of one of the two San Bernardino shooters, Syed Rizwan Farook, the government eventually sought – and won – a court order compelling it to do so.

Wasting no time, Apple said it would still demur, arguing that it was essentially being asked to build a special “back door” into the smartphone. Its case for not helping the FBI get to the bottom of the worst terror attack on US soil since 9/11 and ascertain, for instance, whether there was a wider network helping Farook and his wife, Tashfeen Malik, was laid out by CEO Tim Cook on the Apple website.

The feud between the government and one of the world’s most powerful private corporations could end up before the US Supreme Court before it is resolved. The issues involved are as confounding for ordinary citizens as they are for legal scholars with no one able to say who will win - or who should win. The case will be closely watched by other nations wrestling with the same conundrum, including China.

The order was issued on 16 February by Judge Sheri Pym of the Central California District Court. It required Apple to bypass security functions on the cellphone that had been used by Farook. He and Malik, inspired by Isis, opened fire at a pre-Christmas lunch for employees of the San Bernardino health department, where he worked killing fourteen. Both assailants were themselves killed later by police.

For Apple and Google, responsible for the technology in the vast majority of cellphones in America, data protection is of singular commercial importance at a time of heightened concern about identify and data theft. An iPhone will permanently disable itself after ten failed attempts to unlock it with an incorrect password. While locked, all the date on a phone is encrypted.

But if the country is newly on edge about terrorism it is because of San Bernardino. “We have made a solemn commitment to the victims and their families that we will leave no stone unturned as we gather as much information and evidence as possible,” the chief prosecutor for the Central California District, Eileen Decker, said of the Apple order. “These victims and families deserve nothing less.”

But Mr Cook insisted in his letter posted on the Apple site that while the company has “no sympathy for terrorists”, what the government was asking was “an unprecedented step, which threatens the security of our customers” and “which has implications far beyond the legal case at hand.”

The court order relied on a less-than-contemporary law of 1789 called the ‘All Writs Act’. This, in part, is a result of the failure of the US Congress to revisit and update for the data age, the slightly less archaic ‘Communications Assistance For Law Enforcement Act’ of 1994.

Presenting itself as the defender of everyman, Apple is contending that once the government has the means to “hack” into one iPhone, who can be certain it won’t use it to hack into others in the future?

“The implications of the government’s demands are chilling. If the government can use the All Writs Act to make it easier to unlock your iPhone, it would have the power to reach into anyone’s device to capture their data,” Mr Cook wrote. “The government is asking Apple to hack our own users and undermine decades of security advancements that protect our customers - including tens of millions of American citizens - from sophisticated hackers and cybercriminals.

“The same engineers who built strong encryption into the iPhone to protect our users would, ironically, be ordered to weaken those protections and make our users less safe. We can find no precedent for an American company being forced to expose its customers to a greater risk of attack.”

The watchdog group The Electronic Frontier Foundation, quickly came down on the side of Apple. “The government is asking Apple to create a master key so that it can open a single phone,” it said in response to the court order. “And once that master key is created, we’re certain that our government will ask for it again and again, for other phones, and turn this power against any software or device that has the audacity to offer strong security.”

Rights and wrongs: The legal situation

The case for

The US Attorney’s Office in Los Angeles has filed a 40-page document requesting Apple’s help in finding “relevant, critical” data on the phone of Syed Farook, who murdered 14 people and injured 22 others with his wife Tashfeen Malik in San Bernardino.

The FBI admits that despite having the phone in its possession, it has been unable to unlock the device – perhaps testament to Apple’s security. The US Courts believe Apple should provide “reasonable technical assistance” to the FBI. It is believed that unlocking the phone could reveal who, if anybody, the couple were communicating with before they launched the attack.

The case against

In a statement that very much reflected Apple’s ethos of data protection and transparency with customers, chief executive Tim Cook refused to unlock the device, claiming it would be a threat to the data security of all users. That claim, while potentially legitimate, opened the company up to accusations that it was failing to aid the investigation into a terror plot.

Mr Cook ruled out creating a “backdoor” into the iPhone as the FBI had requested. He claimed the software did not exist to access the encrypted phone. He said the creation of such software would allow the creation of a “master key, capable of opening hundreds of millions of locks”.

Mr Cook calls the FBI’s demands “chilling” and an “overreach”. Others disagree.

The All Writs Act

The Act was originally part of the Judiciary Act of 1789 and authorises the US federal courts to “issue all writs necessary or appropriate in aid of their respective jurisdictions and agreeable to the usages and principles of law”.

The Act has been used several times recently, including in November 2014, when the US Attorney’s Office in New York cited the Act to demand that Apple unlock an iPhone 5s as part of a criminal case.

Jennifer Aldrich

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks