An interview with Pieter Hugo: the South African photographer on life, death and the aftermath of killing

Andy Martin spends an afternoon with Pieter Hugo, whose gritty and melancholic photographs capture the lost generations of Rwanda and South Africa

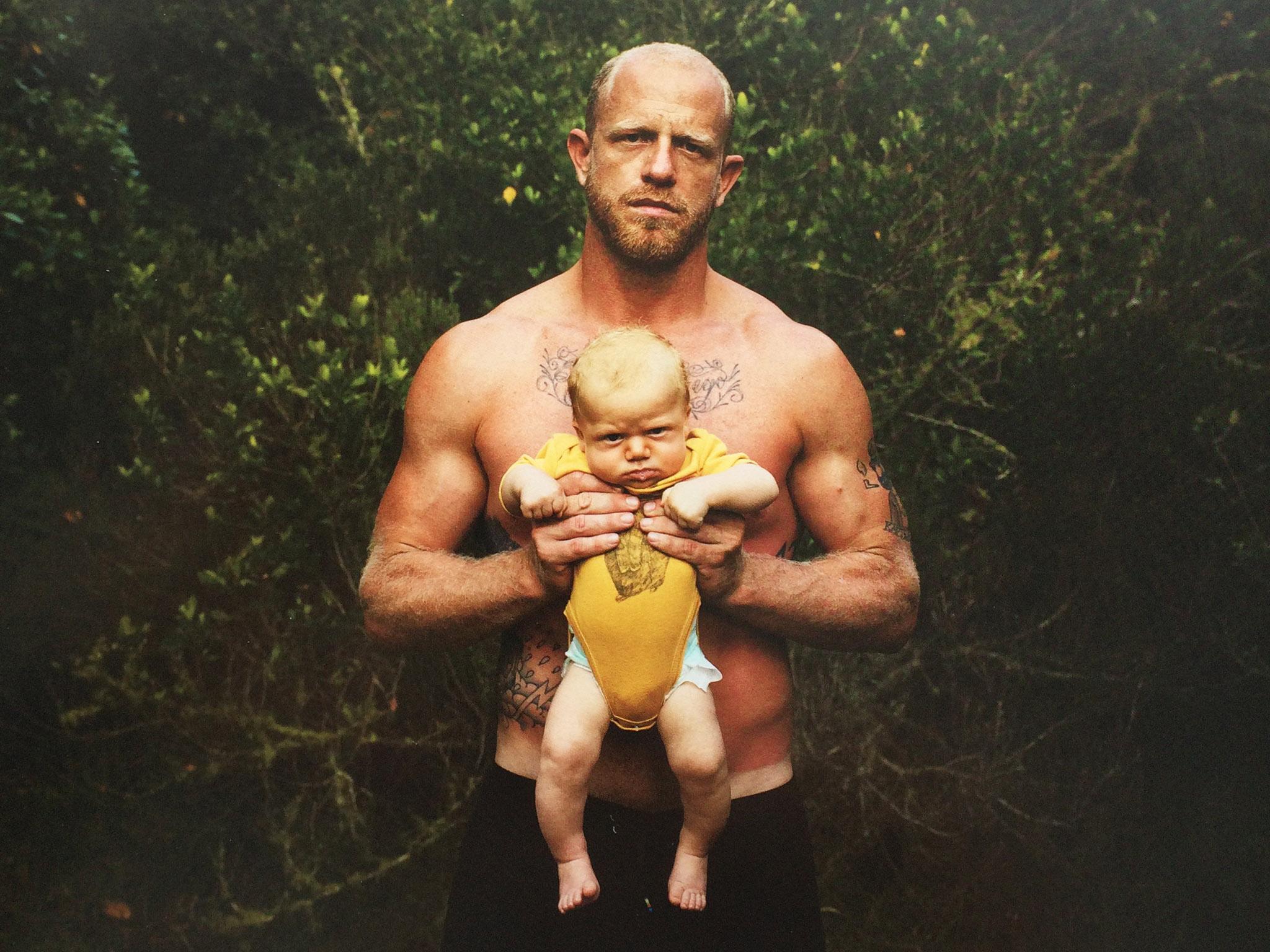

If you look very carefully at a picture of Pieter Hugo and his son, you will notice a couple of things. The father has sunburn. Look just above the shorts. He has been in the water for seven hours when he takes this picture. A mad surfer. And the kid, who already looks as grumpy as it is possible for a kid to look, also has a blob of spittle hanging from his lower lip. The picture is unsentimental, therefore believable. There is no fluffy Photoshopping. No romance. It’s gritty, moody, possibly even melancholy. Maybe the best word is “unresolved”. It’s his word.

Pieter Hugo really surfs. He has a few secret spots around Cape Town that he declined to reveal to me. But surfing is also, inescapably, an allegory. The wave rises up, it peaks, you ride it for a while, then it collapses and dies, sometimes it takes you down with it. All of Hugo’s photography deals with what happens after the wipeout. Hugo calls it the “post-revolutionary phase”, whether it’s in Rwanda or South Africa.

1994 was the making of him. His coming of age and his genesis. All of his work is linked to it. He was 18, in his last year at school. “Mandela was being elected. A time of hope. At the same time we were seeing all this footage on TV from Rwanda of bodies floating down the river.” When he went to Rwanda 10 years later, on his first job, there were still corpses piled up everywhere. “Unlike Germany where genocide was industrialised and out of sight, in Rwanda it was all over the landscape – every banana plantation, every church was a site of massacres.”

He had been given a brief by some NGO. Perpetrators and survivors. “People who had done terrible things and had terrible things done to them.” He even had a check-list: woman: raped; with Aids; on retro-viral drugs; happy. But it was a school holiday, there were kids hanging around at the end of the day, so he took a few random shots. “There was something in these kids I hadn’t seen before.” Then he went on holiday, took a picture of his own daughter. Finally he went back to Rwanda and zoomed in on young people, ranging in age from three to16, some in their Sunday best, some in clothes he had bought from the market, dated and unfashionable. “High fashion for Upper East Side ladies in the seventies.” He shot them against idyllic, almost Gauguin-like backgrounds. “It’s our fantasy of the natural state. Africa. Arcadia.” There is a dysjunction.

His work takes time. It’s not like a fashion shoot or pure reportage. “The picture takes 1/125th of a second. The photographer is always trying to compensate for that brevity, to extend the process.”

In the entrance to his warehouse studio in the Gardens area of Cape Town there is a big sign emblazoned with a skull and crossbones: PIETER HUGO & SONS… FUNERAL UNDERTAKERS. It’s a joke by one of his friends, but there is a truth in it: Hugo is concerned with death, and killing, on an industrial scale, but above all with the aftermath of it. I looked at a couple of collections of his photographs while I was there: ‘KIN’ and ‘RWANDA 2004: VESTIGES OF A GENOCIDE’. All of his works link those two themes. “Your mum and dad fuck you up,” he said, quoting Larkin.

His photograph of two brothers, one carrying the other in his arms, harks back to the picture taken in Soweto in 1976 of an anguished Sam Nzima carrying a wounded Hector Pieterson. The photograph, the snapshot, the “instantané” as the French have it, manifests a buried history, a whole archaeology of the sins of the father. “I wanted them to feel empowered in the pictures, not just victims.”

Pieter Hugo has a tattoo of Captain Haddock (“Kaptein Sardyn”) on his left arm. You can just glimpse it in the photo. “My wife suggested it,” he said. “She thinks I’m like him. She’s probably got a point. I get emotional. I like a drink once in a while. And I’m loyal, I think.” He is never going to be a diplomat. “Look at South Africa now,” he said, gazing out of the window at the street below. “It’s like Russia. Zuma is an ex-spook, like Putin. And it’s all about self-enrichment now. The opportunists have taken over. You want to know what makes me despondent? These problems could be solved. But they aren’t.” His photography is like that. Unrectified. Unsolved. All his subjects, young or old, are caught, as surfers would say, somewhere in "the impact zone".

Pieter Hugo's 1994 series

...in his own words

I happened to start the work in Rwanda but I’d been thinking about the year 1994 in relation to both countries over a period of 10 or 20 years. I noticed how the kids, particularly in South Africa, don’t carry the same historical baggage as their parents. I find their engagement with the world to be very refreshing in that they are not burdened by the past, but at the same time you witness them growing up with these liberation narratives that are in some ways fabrications. It’s like you know something they don’t know about the potential failure or shortcomings of these narratives…

Most of the images were taken in villages around Rwanda and South Africa. There’s a thin line between nature being seen as idyllic and as a place where terrible things happen – permeated by genocide, a constantly contested space. Seen as a metaphor, it’s as if the further you leave the city and its systems of control, the more primal things become. At times the children appear conservative, existing in an orderly world; at other times there’s something feral about them, as in Lord of the Flies, a place devoid of rules. This is most noticeable in the Rwanda images where clothes donated from Europe, with particular cultural significations, are transposed into a completely different context.

Being a parent myself has shifted my way of looking at kids dramatically, so there is the challenge of photographing children unsentimentally. The act of photographing a child is so different – and in many ways more difficult – to making a portrait of an adult. The normal power dynamics between photographer and subject are subtly shifted. I searched for children who seemed already to have fully formed personalities. There is an honesty and a forthrightness which cannot otherwise be evoked.

Pieter Hugo, Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea, published by Prestel

Pieter Hugo's 1994 series was on display at New York's Yossi Milo gallery. For more exhibition news visit yossimilo.com, or alternatively on twitter @yossimilo

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks