Russian plane crash: What we know about flight 9268 – and what we don't

Speculation has raged among everyone from politicians to pilots about the cause of the tragedy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Early on Saturday, 224 people died when the Airbus A321 that was flying them home from Sharm el Sheikh to St Petersburg crashed in the Sinai Desert. Ever since, speculation has raged among everyone from politicians to pilots about the cause of the tragedy.

Flight 9268 took off on from the Egyptian resort shortly before 4am GMT on 31 October and climbed normally to 30,000 feet. Within half-an-hour, without broadcasting a Mayday, the aircraft crashed in the desert. Beyond that, much of what has been said is conjecture rather than fact.

Q| What do we know about the airline?

Following the break-up of the Soviet Union, dozens of small carriers started up - including Kogalymavia, the operator of flight 9268 under the Metrojet brand. Most of the 20 crashes of Russian passenger jets in the past two decades have involved such airlines.

Q| And the plane?

The Airbus A321 was built in 1997, which makes it relatively old. The design is a stretched version of the Airbus A320, which is a workhorse for airlines around the world. It has a better accident record than its nearest rival, the Boeing 737, and is well regarded by pilots.

Q| What could have caused the crash?

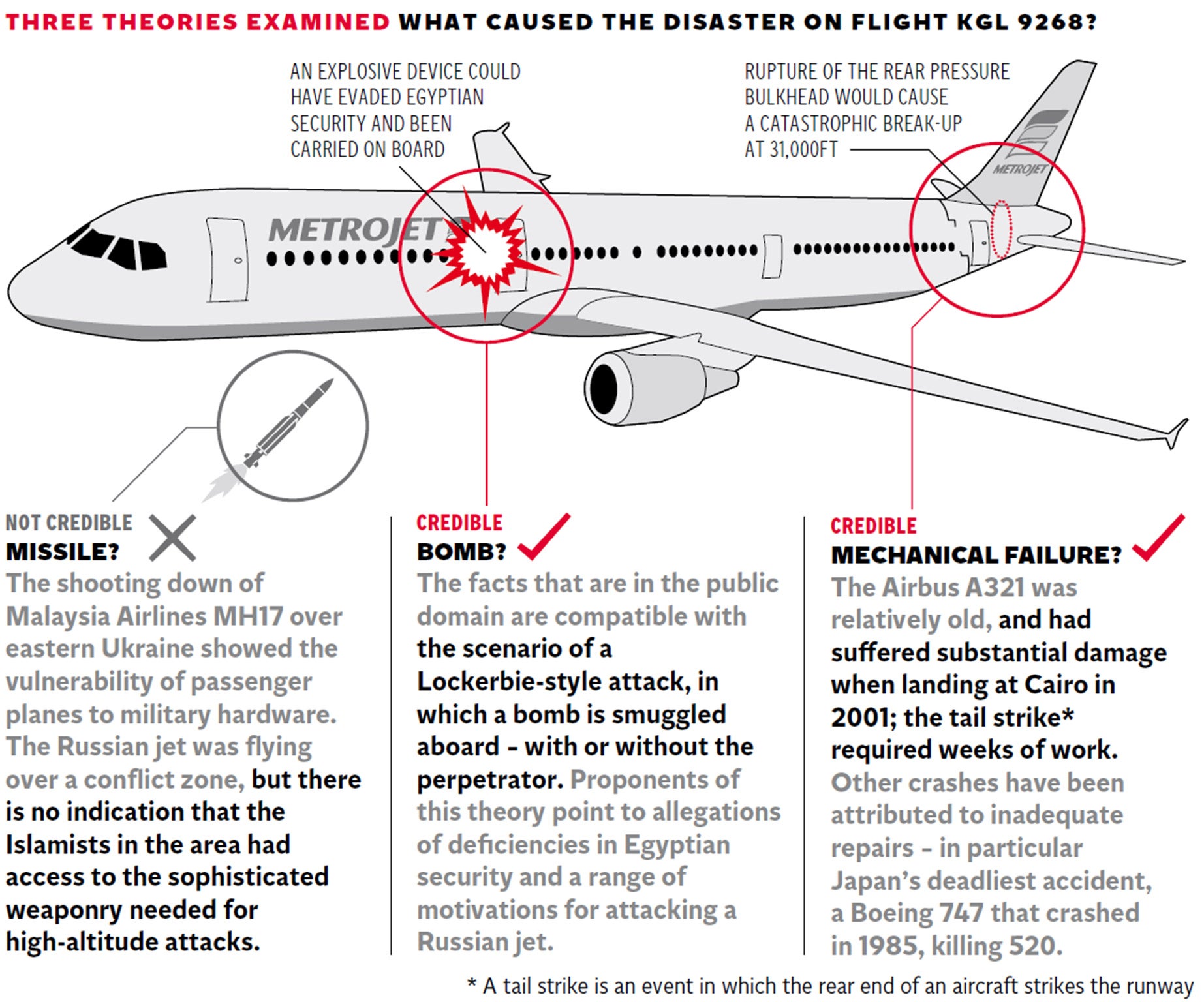

In many air crashes, there is often more than just a single cause – and it may well prove to be the case for flight 9268. The investigators will be studying everything from the health records (mental and physical) of the pilots to the commands they made. But in the days since the crash, theories have coalesced around three broad theses: catastrophic mechanical failure, a bomb on board or a missile attack.

Q| What evidence is there for a mechanical failure?

Some have speculated that the aircraft's pressure bulkhead, part of the system that seals the cabin from the much lower outside pressure, may have failed. The aircraft operator insists the A321 was properly maintained. However, freely available records show that the aircraft lost on Saturday had encountered structural damage while flying for Middle East Airlines in 2001. The tail struck the runway while landing at Cairo.

Other crashes have been attributed to inadequate repairs - in particular Japan’s deadliest accident, a Boeing 747 that crashed in 1985, killing 520. In the past 40 years, though, maintenance standards have improved dramatically. particularly in terms of structural integrity. But the history of aviation safety is littered with cases in which unforeseen combinations of circumstances have caused disaster.

Q| If it was a bomb, who planted it – and were they on the plane?

There are plenty of armed groups with motives for attacking a Russian passenger jet, from Chechen separatists to so-called Islamic State. If it was a bomb, it could conceivably have followed the method used in the Lockerbie bombing in 1988, in which a bomb was concealed in passenger baggage but the perpetrator did not fly. Current security measures should not make that possible. Other scenarios include an “inside job”, with an employee at the involved in planting a device, or a suicide bomber who succeeded in evading security.

Q| Were there warnings in place about overflying the area in case of a missile attack?

Yes, because of the perceived risk of an attack using shoulder-launched missiles - known as man-portable air defence systems (MANPADS) - by rebel forces fighting in the Sinai. Pilots were warned to stay above 25,000 feet to avoid “dedicated anti-aviation weaponry,” and airlines were “strongly advised” to take the risk into account when planning routes.

Q| So why did the Russian plane fly over the region?

Because the most direct track from Sharm el Sheikh to St Petersburg passes directly over the middle of the Sinai. The captain planned to overfly the area at an altitude well above the height perceived as potentially dangerous. Even after the shooting down of Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 over eastern Ukraine last year, it is still routine for commercial flights to traverse conflict zones if there is no evidence of advanced weaponry capable of reaching six miles high.

Q| A Russian-operated, French-designed, German-built, American-engined, Irish-owned aircraft flying from Egypt. So who’s in charge of the investigation?

With everyone from the Kremlin to US security officials pronouncing on the crash, the nervous passenger would be forgiven for thinking the accident investigation is a mess. But international rules make it quite clear that Egypt’s Aircraft Accident Investigation Central Directorate, part of the Ministry of Civil Aviation, is the body responsible for the investigation. Representatives of the other interested parties are also involved, which could be a possible source of some of the leaks so far. The only official source is the Egyptian investigation team.

Q| How good are they – and can we believe them?

The basis of incident investigation is to improve flight safety. That means getting the facts and being totally open. Like other major countries, Egypt has some excellent aviation safety officials who have done good work on past crashes. Some, though, voice the fear that the investigators will face political pressure from Cairo, and possibly Moscow, to reach “convenient” conclusions. Western pilots have pointed to the investigation into Egyptair flight 990, which crashed into the Atlantic between New York and Cairo in 1999. The US National Transportation Safety Board found that the probably cause was a suicidal pilot, but in a parallel investigation the Egyptians insisted it was mechanical failure.

Q| When will we know more?

It is likely that an interim report, revealing some of the facts contained in the “black boxes” and among the wreckage, will be published in the next few weeks – though with such intense pressure it may be that something appears sooner, or conversely that investigators delay publication to make certain their report is watertight.

A final report is likely to take much longer.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments