Morocco’s forgotten terror attack

The small-scale ambush claimed the lives of two Scandinavian women and, as Greg Miller and Souad Mekhennet find out, it raises concerns about the lengths people will go to for Isis to recognise them from afar

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Their screams must have carried for miles in the thin air of the Atlas Mountains, anguished sounds of a terrorist attack that no one was there to hear, see or stop.

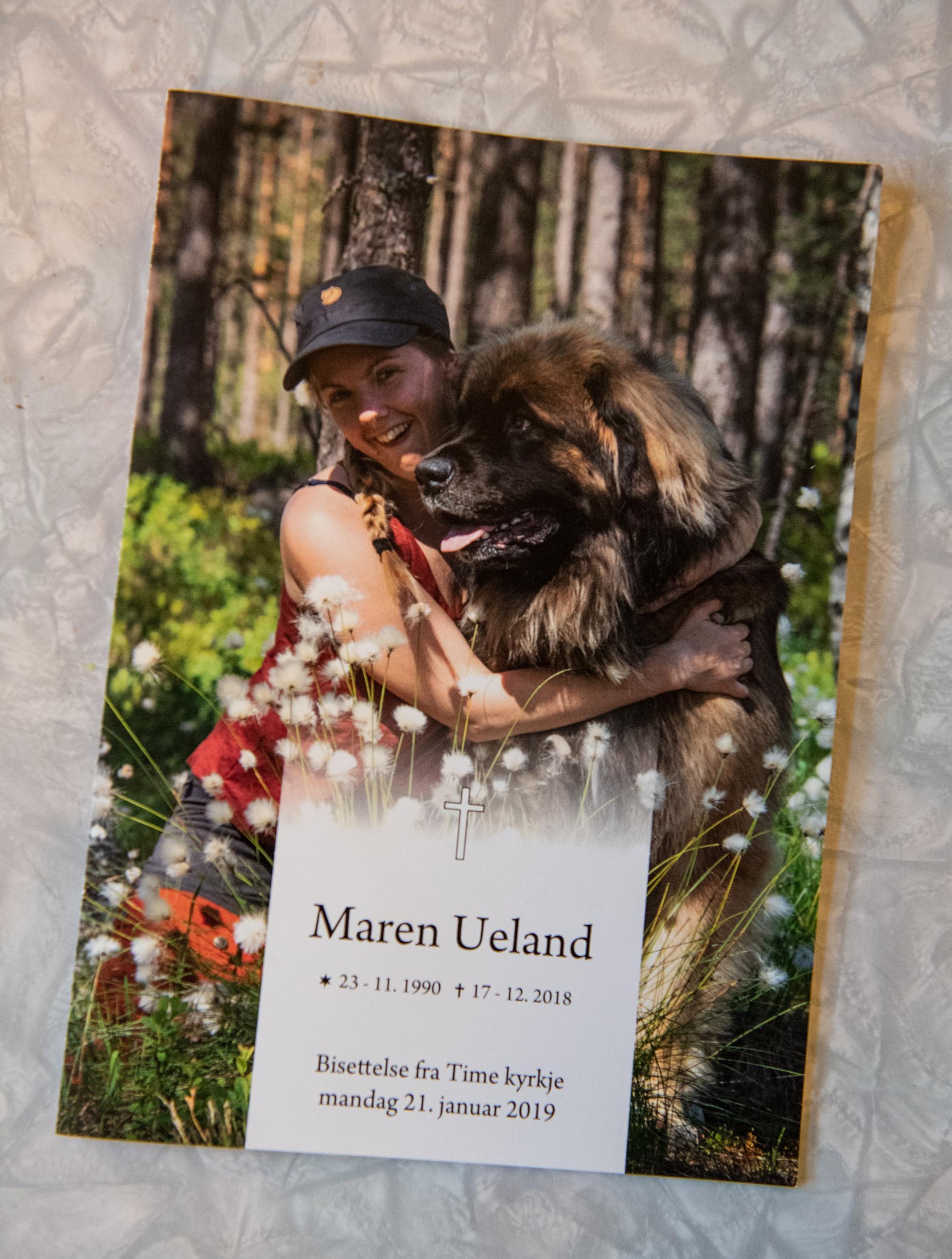

Maren Ueland, 28, and Louisa Jespersen, 24, Scandinavian students who revered the outdoors, were descending north Africa’s highest peak in December when they encountered four men searching for westerners to kill.

The men waited until after nightfall, then approached the women’s tent with knives and misplaced hopes of becoming Islamist heroes. They attacked Ueland, a Norwegian, and her Danish friend, Jespersen, in their sleeping bags, stabbed them until their bodies went limp and severed their heads in a ghastly sequence recorded on a cellphone.

The December 2018 attack, like so many in this age of mass killings and social media, was an act of senseless and performative violence. The killers, poor and uneducated, became absorbed in a violent Islamist universe they saw on the screens of their cellphones, then sought their own place in it. Their overriding aim was to impress the Isis, earn the status of soldiers in its apocalyptic struggle and see their own recording distributed across the group’s propaganda platforms.

Reality didn’t follow that script. The targeting of defenceless women and the abysmal quality of the recording managed to violate the standards of a terrorist group not known for having any. The Islamic State did not distribute the video, refused to acknowledge the attack and to this day has ignored the Moroccans’ pledges of loyalty.

The video went viral nonetheless. An attack that had gone unheard and unseen ended up being viewed millions of times by Isis supporters who didn’t share the group’s selectivity, by dark web bottom dwellers devoted to gore and by the morbidly curious.

The most alarming audience, however, was one that the attackers had not envisioned. Within days, the one-minute, 16 second recording spread rapidly across networks associated with the far-right and white-nationalist movements. Extremists posted gruesome scenes of the women’s deaths on Facebook, Twitter and other platforms alongside condemnations of Islam and calls for a civilisational clash.

“Look at this video of the one girl being decapitated alive,” wrote a far-right figure in Norway as he posted a link to his Twitter account. “It’s God awakening us Germanic men to action. It’s enough now. It’s enough.”

When officials in Norway and Denmark pleaded with the public to stop sharing the video, that effort was denounced by far-right groups as a betrayal of religion and race – censorship of content that revealed the true nature of Islam.

For families of the victims, the aftermath compounded the pain. Their mothers were inundated with messages on Facebook. Many were expressions of condolences, but some were gestures of astonishing cruelty, saying their daughters deserved to die and attaching links to the video of their slaughter.

The attack in Morocco was not of the same magnitude as the mass shooting that killed 51 people at mosques in New Zealand three months later, or the Easter bombings in Sri Lanka five weeks after that, when more than 200 people attending church services were killed. But all are part of a pattern of violence and viral incitement in which the extremes of intolerance react to and further radicalise one another online.

In the Moroccan case, a video that was created to strike a blow for Islamism was almost immediately repurposed and weaponised by those who consider the religion an existential threat to the ethnic and cultural identity of northern Europe.

The victims were caught between warring ideologies that they had rejected in life. In the days after the attack, far-right activists scoured the women’s social media accounts and mocked them for their tolerant views.

“It is obvious to point out the naivete of the two deceased, but they are, as all, a product of their upbringing,” says an entry on Uriasposten, a Danish, anti-Islamic website. “Perhaps the eternal struggle against ‘prejudice’ has unpleasant side effects.”

Select your targets and carry out a strike, for a piercing bullet, or a stab deep in the intestines, or the detonation of an explosive device in your lands is akin to a thousand operations here with us

This account of the attack in Morocco and its aftermath online is based on Moroccan court records including statements from the suspects; interviews with officials in Morocco, Norway, Denmark and the United States; and friends and relatives of the victims and of the suspects in their deaths.

Ueland and Jespersen were among five students from a university in southeastern Norway who had been planning their travel to Morocco for months, and they wanted to hike its tallest mountain. “Dear friends, I am going to Morocco in December,” Jespersen wrote on Facebook last year. She asked for tips from “any mountain friends who know something about Mount Toubkal”.

They were part of a university programme on “outdoor life” that encourages students to gain a deeper connection with nature. It is an unusual academic discipline, even in Norway, a country of outdoors enthusiasts where the rugged landscape is regarded as a national treasure.

Students are also taught navigational and survival skills, what to pack and how to cook, where to set up camp, and how to assess risks such as rockslides, wild animals and extreme weather.

Eleven days before the attack, Ueland had submitted her final paper for a class on “ecophilosophy”. She wrote about her upbringing on Norway’s west coast, and described being outdoors as both an antidote to the “need to know everything” in the digital age and a unifying experience across cultures. “We need to tend to it,” she wrote of the natural world, “and build relationships of care and understanding to each other”.

Though well-suited as travel companions, Ueland and Jespersen had different temperaments. Jespersen was more outgoing. Ueland was more reserved and less willing to leave things to chance. In the days before their departure, Ueland became stressed about uncertainties in their itinerary and briefly considered backing out. But a conversation with Jespersen restored her enthusiasm, and they departed from Oslo on 8 December.

Irene Ueland, Maren’s mother, spent several days with her daughter near the university campus in the village of Bo, stitching repairs into her favourite travel shorts and helping her pack.

In the ensuing days, they were in touch sporadically by text. “Hello, everything is good down here – I don’t have the mobile on so much,” Maren wrote on 9 December.

“That’s good but I need to hear from you about what you are doing and whether you are having fun,” her mother replied.

Three days later, on 12 December, Irene wrote again: “Is it going OK with you and Louisa?” Receiving no response, Irene sent another message: “Maren you have to give me a signal so I won’t be so afraid something is wrong.”

A day later, in an impoverished neighbourhood a short drive from the tourist districts of Marrakesh, four bearded militants propped a cellphone against the cushions of a worn couch and seated themselves under an Isis flag they had fashioned from a T-shirt.

“Feel your necks, oh enemies of Allah,” one of them said before they all took a common oath to the leader of the Isis: “We affirm our allegiance to the emir of the believers and the caliph of Muslims, Ibrahim Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.”

The men, in their twenties and thirties, were making their own final preparations for a trip into the Atlas Mountains after years of fantasising about how they might carry out a terrorist attack.

They were part of a broader, loosely affiliated network of Islamists in the Marrakesh slums. Their commitment to extremism varied, but one had radical credentials the others lacked.

Abdessamad Ejjoud, 26, was a street vendor who had aspired to travel to Syria in 2015 and been convicted of supporting the Isis. He spent a year in a Moroccan prison, where he mingled with other militants and hardened his views on Islam. After his release, he gave up on getting to Syria and “decided to replace this project by planning and preparing the implementation of jihad projects in Morocco,” according to Moroccan court files we obtained.

He functioned as the ringleader of a group that grew to exceed two dozen people, and communicated through Telegram, an encrypted messaging application. At the group’s core were Ejjoud, Rachid Affati, 33, Younes Ouazid, 27, and Abderrahmane Khayali, 33.

As early as 2017, they were contemplating an assortment of improbable plots. They mixed store-bought ingredients to make an explosive device, but gave up when it fizzled. They found an online recipe for a lethal balm – consisting of rat poison, hand lotion and anti-inflammatory cream – that they planned to smear on the car doors of Moroccan security officials. But they discarded the idea after a disappointing experiment on a rabbit.

They cycled through other grandiose schemes: storming resorts with swords; ploughing through crowds of tourists in rented cars; attacking popular tourist sites with suicide belts. They practised assault sequences at a paintball facility but struggled to acquire actual rifles.

In 2018, they began focusing on more feasible plans, and made a reconnaissance trip to Imlil, a picturesque village that serves as a tourist gateway to the Atlas range. They camped for days, reading Islamist literature and singing militant hymns.

At the same time, they monitored events in Syria, where Isis’s territory was steadily shrinking. In August, the terrorist group released an audio recording of Baghdadi urging followers beyond Syria to launch a new wave of attacks.

“Select your targets and carry out a strike,” he said, “for a piercing bullet, or a stab deep in the intestines, or the detonation of an explosive device in your lands is akin to a thousand operations here with us.”

Shortly after, Ejjoud convened a meeting in which he spoke of “the need to respond to the calls of the organisation’s leaders”, according to court files.

In mid-December, Khayali went to a drugstore to buy bottles of black and white dye that he used to make the rudimentary Isis flag they used as a backdrop in the allegiance video recorded in his home.

On 14 December, the four men packed knives, a tent and cellphone cards. They rode motorcycles to the outskirts of Marrakesh, then took a taxi to Imlil, where they bought food and camp stove fuel at a supply store.

Their first two days were marked by several abortive attacks. The day they arrived on the mountain, a Friday, they spotted a pair of tourists on bicycles and “took out their knives to target them but they ultimately stepped back,” according to court files that did not explain why. On Saturday, they began tracking two different tourists, only to put the blades away again when they realised that the hikers were accompanied by guides. They also considered targeting a solo British hiker but were either spooked by villagers or dissuaded when they realised he was Muslim.

They woke the next morning, on Sunday, with plans to set a trap high on the mountain trail, using a narrow passage as a place to stage an ambush.

When that did not work, the cell faced a defection. Whether fed up or frightened, Khayali, who had left behind a wife who was pregnant with their third child, declared that he would not continue. He went back down the mountain and returned to Marrakesh.

While the Moroccan plotters were squabbling, Ueland and Jespersen completed their multi-day trek to the top of Jebel Toubkal, a 13,000ft summit blanketed in snow.

The trail back to Imlil is rugged, with steep descents, large boulders and tight turns. As evening approached, the women arrived at a rustic rest stop – a shop that sells snack items, drinks and water from a stream.

Ahmed al-Kadi, 29, who has operated the shop for years, said he did not recall seeing Ueland and Jespersen on their journey but had a vivid encounter with the Moroccans. The men asked to use his storage shed for prayers, so he laid out burlap sacks for them to use as rugs, and gave them water to wash. They thanked him and departed, heading uphill.

As sundown approached, al-Kadi closed shop and went back to Imlil. Ueland and Jespersen arrived sometime after. They were only a 45 minute walk from the village but decided to use the level surface along the north-facing wall of al-Kadi’s shop as their tent site for the night.

Ejjoud and the others had encountered the Scandinavian hikers at a higher elevation that day, though it is not clear whether the two groups had spoken. The plotters took note of where the women placed their tent and continued 150 yards downhill to erect their own shelter within sight of the trail.

That night, the three remaining Moroccans discussed their division of labour. Ejjoud and Ouazid would kill the two women, while Affati would film the attack on his mobile phone. It was after midnight when they approached the women’s campsite.

Ouazid shouted, commanding them to come out. As he reached for a zipper on the tent, he was startled by Jespersen’s hand groping for the tab from the other side. He swung his knife at her hand and sliced it, setting off a violent struggle punctuated by piercing screams.

The men stabbed through the tent’s nylon fabric at the panicked figures inside. Jespersen managed to break out of the tent and tried to run, only to be subdued with multiple stab wounds. Affati, aiming the camera, pinned her head to the ground with his foot while Ejjoud attacked her with a knife. “This is the revenge for our brothers in Deir al-Zour,” he said, referring to a province in eastern Syria where the Isis had sustained heavy losses.

Inside the tent, Ouazid found Ueland “sitting without any movement,” according to the court files. He stabbed her in the chest, back and arms, and emerged from the tent carrying her head.

The men fled downhill toward Imlil, stopping at a stream to wash their clothes and shave their beards. Once they were close enough to the village to have a strong cell connection, Ejjoud transmitted two recordings via Telegram: the allegiance video and footage of the attack. Both were to be passed through intermediaries to Isis propaganda outlets including its news agency Amaq.

The bodies were discovered by a pair of French hikers who arrived at the blood-soaked campsite the next morning, on 17 December. As the hikers ran frantically back towards town, they encountered the shopkeeper on his way up. Within hours, the ordinarily tranquil trail was off-limits to tourists, clogged with emergency vehicles and gendarmerie.

Back in Norway, Irene Ueland, who is an amateur nature photographer, was with her brother at a framing shop. She told him she was nervous because she had not heard from Maren in five days, and he sought to reassure her that Morocco was safe.

That afternoon, Norwegian television reported that two women, from Norway and Denmark, had been found killed in Morocco, but their names were not disclosed.

Maren’s stepmother saw the report and called her husband, who was working that day at a farm. She noted that the newscasters mentioned women from Norway and Denmark and asked where Maren’s companion was from. “That’s concerning,” he said, “because she is Danish.”

The father called Maren’s sister, Malin, who quickly relayed the news to their mother. At that moment, she was with her son, Maren’s brother. Malin emphasised that the victims’ identities were not yet known, but her mother was already beyond consolation.

“I feel it. I feel it,” Ueland said. She hugged her son and told him she needed to leave. As she drove away, she dialled the emergency number of the Norwegian police, explaining that her daughter had been hiking where the victims were found.

“Is it her who is killed in Morocco?” Ueland asked.

The police said they didn’t know. Moments later, they called back.

“Where are you?” the voice said.

“In the car,” she said.

“You have to pull over.”

Though the three attackers had transmitted their videos early Monday, there was no sign of the recordings online for several days. Inside the Isis, guardians of the terror group’s brand evaluated the two submissions and found them deficient in almost every way.

In the allegiance video, the Isis flag the Moroccans had crafted from a T-shirt was shoddy and misshapen. The men sat huddled in a darkened room like slovenly teenagers, mumbling their oaths, not in classical Arabic but in a crude regional dialect.

The video of the attack was even worse. The footage was so shaky and dark that it was difficult to make out – in contrast to the elaborately staged executions in Syria. The fact that the men fled into the darkness was also at odds with the valiant image the Isis seeks to project.

But it was the targeting of unarmed women that appears to have been the greatest affront. European officials who have poured over the terror group’s propaganda archives have documented the deaths of 2,070 people in filmed executions between 2015 and 2017, mostly in Syria and Iraq. Only three of those killed were women – either stoned or shot for alleged offences, their faces hidden in accordance with Islamic strictures.

The Moroccans violated those religious tenets. Ueland and Jespersen were killed in their underwear, their faces, necks and shoulders often in the camera’s view.

Inside Isis chat rooms, followers catalogued these failures, though without sympathy for the women killed. “This operation was an individual one by the brothers who are supporters,” one post said. But “they had been warned about disseminating a video without covering the naked bodies of the female prostitute tourists.”

Nico Prucha, a terrorism expert based in Madrid who monitors Isis’s media output, says he could find no indication that either the attack or the allegiance video was ever even mentioned on Isis propaganda channels.

“The Moroccan attack was botched from the rhetorical side to the operation side to the theological side,” Prucha says. “It was just a complete failure.”

But elements seen as irredeemable to the Isis were symbolically potent to the far right, especially anti-Islamic factions that cast themselves as protectors of white women and guardians of Nordic and Scandinavian bloodlines.

The Morocco attack “feeds directly into the way the white supremacist movement conceptualises itself,” says Brian Fishman, a terrorism expert who oversees Facebook’s policies on extremist content. “The way that is crystallised is as a defence of white women.”

It remains unclear where the attack video first surfaced. European investigators said it initially appeared on Facebook, then spread to other platforms, though Facebook officials said they could not confirm this. The allegiance video was posted first by a Twitter account called WikiDawla, a reference to Isis. The account appears to be operated by an individual who claims to reside in the United States, but who in several interviews with us refused to reveal his identity or offer proof of his US residency.

By Wednesday, 19 December, the attack video was on multiple platforms, including Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp and Telegram. Even those closest to the victims found themselves unable to escape the indiscriminate spread.

Stine Holm Kvisselgaard, a classmate of Ueland and Jespersen’s, had initially planned to join them on their hike in the Atlas range but decided at the last moment to remain with two other students headed to the Moroccan coast for a surfing trip.

When they learned that two women had been killed in the mountains, Kvisselgaard sent Jespersen a desperate note: “When you get safely down from the Atlas mountains will you give us a text? I’m trying to do my best not to be very afraid that it is you.”

The three returned to Marrakesh, where they were questioned by Moroccan police, sought help from their countries’ embassies and tried at times to distract themselves in the markets around their hotel as they waited for flights home.

Meanwhile, the video was proliferating around them, popping up on thousands of Moroccan cellphones. In a spice market, the two students encountered a merchant with a stricken look. “We asked him if everything was OK and he said no, that he had just seen something horrible on his phone,” Kvisselgaard says.

She called the Danish Embassy to ask if authorities there had seen the video. The official she spoke with said she was aware of the recording but had not seen it. Kvisselgaard interpreted the exchange as a request to “track it down and send it to them”. She spent the next hour trying to secure a copy, even though the Danish ambassador and other officials by that time had obtained the footage from Moroccan authorities.

Back in the students’ hotel room that night, Kvisselgaard tried to delete the footage from her cellphone, but as she clicked it, the video started playing. For several excruciating seconds, she fumbled with the buttons on her phone, trying to make it stop.

In Norway, Irene Ueland’s Facebook page began filling up with enquiries from friends – was it Maren who had been killed? To answer, she posted a black-and-white photo of Maren with the years of her life, 1990-2018.

After the attack video surfaced online, the flow of Facebook messages surged again. Some were apologetic notes from strangers, including many in Morocco, expressing sorrow. But a vicious new strain began to appear. Supporters of the militants posted messages on both mothers’ pages saying that their daughters had died because of the west’s hostility to Islam. Denmark and Norway have both deployed troops to Syria as part of a US-led coalition fighting Isis.

Right-wing extremists also entered the fray with postings that depicted the attack on the two hikers as a rebuke of those who would allow more Muslims into Europe. Some posts included links to the video. One message, seemingly oblivious to Ueland’s nationality, said: “You Swedes on the left welcome these savages.” Norway took in about 30,000 Muslim refugees between 2010 and 2016, according to the Pew Research Center – part of a broader influx in Europe accompanied by a surge in anti-Islamic sentiment.

But Norway’s most traumatic experience with terrorism involved the extreme right. In 2011, Anders Breivik killed 77 people – most of them teenagers at an island youth camp – in a massacre that he rationalised in a rambling manifesto that railed against the supposed Islamisation of Europe.

Six days after the Morocco attack, Norwegian prime minister Erna Solberg urged people “not to download or spread the death video. It is the [work] of terrorists, to create fear and anxiety”. But by the time she issued that statement, on 23 December, vandals had posted the video to her own Facebook page multiple times.

Right-wing activists also began promoting the video – or images from it – on their own platforms. Among the most prominent was “Resett”, a Norwegian website that is the country’s closest equivalent to Breitbart in the United States.

On 20 December, editors at Resett pulled four gruesome images from the video and posted them to the website. There was no accompanying text other than a stark headline and a banner ad for a “Make Norway Great Again” hat.

Three days later, as Solberg made her appeal to stop the video’s spread, Resett published an article that criticised the country’s politicians and ended with a diatribe against Islam. “This is a day of anger,” the article concluded, describing Islam as a “hateful ideology that should have been on the scrap heap of history, but is unfortunately still with us ... Even here in Norway.”

Helge Luras, the founder of Resett, defended the publication of the photos as a public service – “to level the playing field” against news organisations that refused to show the pictures and politicians he believes fail to grasp the threat posed by Islam.

A former government analyst, Luras, is known for provocative television appearances and his ardent support of Donald Trump. In an interview, Luras said Resett wouldn’t exist were it not for the result of the 2016 US election. It has become one of Norway’s most widely read websites, sometimes approaching mainstream news organisations in reach.

“What we tell our kids in school is that Islam is like any other religion, that the prophet Muhammad is just like Jesus, a pacifist,” Luras said in an interview. “It is the opposite.” Resett published the blood-soaked images, he said, because “we need to tell people the reality of Islam”.

Facebook, Twitter and other companies worked with authorities to take down the attack video. But the recording continued to proliferate in less-controlled environments online. Danish officials said that it was downloaded 800,000 times in one month from a single website that traffics in gore.

Desperate to deter the video’s spread, Danish authorities turned to a law that was designed to combat “revenge porn” – the posting of explicit images of a private citizen without that person’s permission. So far, 16 people have been charged with sharing or promoting footage of the Atlas attack. Among them were a far-right candidate for parliament in Denmark, and the publisher of a well-known anti-Islamic blog.

In Morocco, it took several days for authorities to apprehend suspects in the attack. The first to be captured was the one authorities said had left the other plotters.

Khayali had returned to his wife and two children – boys aged seven and 10 – with a rattled demeanour and clean-shaven face. He told his wife he had been away on a work project and had removed his beard because of the suspicions it raised. “People keep telling me you are Isis,” he said.

All four family members were asleep in the same room at Khayali’s parents’ home on 18 December when police burst in at 5am and took Khayali away in handcuffs. According to transcripts of his interrogations, Khayali said he had agreed to help the others go into hiding after the attack and that he had tried to call them without success. He also said he realised as he descended the mountain that he had forgotten to leave them with the makeshift Isis flag to drape over the victims’ corpses.

The others eluded authorities for two more days, finally being captured after boarding a bus in Marrakesh. A vendor selling bottles of water had seen one of their knives and alerted police.

Authorities in Morocco ultimately arrested 24 people on suspicion of taking part in the attack or being linked to Ejjoud’s network. In statements and appearances in court, Ejjoud has veered between contrition and defiance.

In late May, he said he and the others “loved the Islamic State and prayed to God for it”. But he also admitted his guilt, according to a BBC report, saying, “I beheaded one of them. I regret it”.

The main suspects face the death penalty if convicted. Though Morocco has not carried out an execution since 1993, an attorney following the case for Jespersen’s family said he believes that lapse will end. “I expect that the four men will receive capital punishment for what they have done to these young, innocent women,” said Khalid El Fataoui, an attorney in Morocco.

In the months since the attack, the families of victims and suspects have gained painful insight into how acts of terrorism reverberate.

Irene Ueland, with the help of a therapist, has worked to limit her bouts of tears to two 20-minute sessions per week. She takes care of Maren’s dog, makes frequent trips to the shore, and obsessively collects a variety of native mushrooms that Maren had often brought home.

Ueland, who hopes to launch an environmental foundation in her daughter’s memory, discovered after the attacks that Maren had carried her own terrorism-related grief. Among the belongings that authorities found at the site of the tent was a letter Maren had received years earlier. It was from a childhood friend, a French girl named Salomé Girard, who was killed in the 2011 bombing of a cafe at a popular tourist spot in Marrakesh. Ueland had carried the letter with her to the city where her friend died.

Maren’s mother said she now realises that her daughter was “very sad about this for many years”. But Maren didn’t mention the letter before the trip, her mother says, possibly because of the worry it would have caused. “She didn’t tell me, because I would have been too afraid and I would have stopped her from going,” Irene Ueland says.

The suspects’ families are engaged in their own searches for answers.

Affati who allegedly operated the cellphone camera during the attack, has four children and for years worked with his own father making stools from salvaged limbs of Eucalyptus trees for sale to tourists. On a recent day, the father stood in his shop – an outdoor stall piled with wood shavings and hand tools – struggling to comprehend.

“Why would he hurt the people who are buying his wares?” he asks. Rachid “is not evil,” he says, but is “sometimes a naive person”.

During a recent visit at the prison near Rabat, Affati told his father that he “didn’t do anything,” his father says, even though his son’s foot is visible in the video holding down Jespersen’s head while Ejjoud cuts her throat.

Khayali, the suspect who left the group, has been separated from his family for more than five months. He was in prison when his wife gave birth to their third child, another son, in March.

On one recent night, three generations of women in Khayali’s family gathered in a room lit by a single, dangling bulb on the outskirts of Marrakesh. Among them were his mother, who is in her fifties, his grandmother, who is in her eighties, and his wife and aunt.

His mother said she felt sympathy for Ueland and Jespersen, but spoke of her son as if he had been drawn against his will into a terrorist cell and was somehow also deserving of sympathy. “The girls were victims like my son,” she said. “This is what God has written.”

When told that Khayali had sworn allegiance to the Isis, his wife shook her head in disagreement. “That is what people say,” she said. “I don’t believe that this information is true.” When a reporter began playing the allegiance video on a cellphone, the four women reluctantly turned their eyes towards the screen. As the recording started, Khayali’s wife noted with a measure of vindication that “only one guy” – Ejjoud – “is talking”.

But as all four men’s voices rose and recited the pledge to Baghdadi, the women buried their faces in their hands and sobbed – another audience that the four men had failed to anticipate.

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments