Inside the murky world of Libya’s mercenaries

Investigation: Libya has morphed into the world’s newest proxy conflict and at its heart is a labyrinth of mercenary recruitment stretching across Russia, Syria and Turkey. Bel Trew and Rajaai Bourhan report

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Morale was so low among the ranks loyal to Libya’s recognised government, a clutch of fighters secretly planned on deserting the battlefield if they were forced to take on the Russians.

The highly-trained mercenaries – hired to support renegade general Khalifa Haftar in his bid to take Tripoli – had emerged from the snarl of Libya’s latest war as the most feared force.

For the malaise of Tripoli fighters, better acquainted with shooting Kalashnikovs in flip flops, the lethal accuracy of the Russians was terrifying. Their sniping capability had become legendary among the rank-and-file.

So when the orders came to march south on the enemy positions, a group of fighters huddled together to discuss how they might escape.

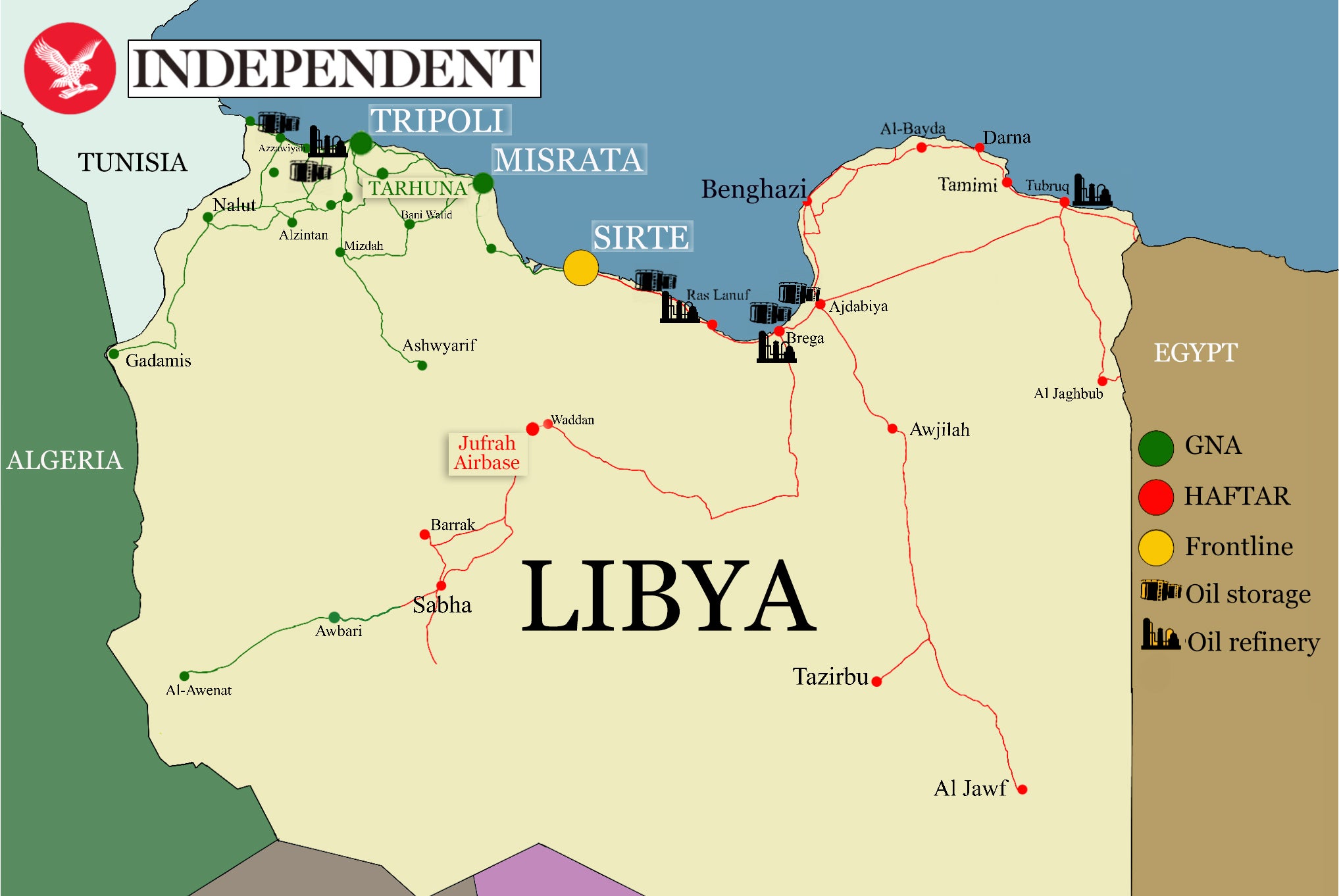

The target was Tarhuna, a crumbling one-street town 60km south of the capital Tripoli. With two tiny airstrips, the little-known backwater had morphed into a vital supply line for Haftar since he launched his offensive last April to take the capital from the Turkish-backed Government of National Accord (GNA).

If the town fell, the renegade general would lose his last foothold in west Libya and the GNA would likely win the war.

The problem was Moscow’s mercenaries in the way.

“We were planning on running away. We were very afraid of the Russians because of their target accuracy. They are incredibly professional in using artillery,” one government fighter admitted, with embarrassment.

“Our main goal was staying alive. It is hard to articulate the fear”.

But before the GNA fighters had even left Tripoli, footage was circulating online showing what appeared to be Russian combatants in trucks and cargo planes retreating from the frontlines.

When the fighters finally arrived in Tarhuna the mercenaries had melted away.

“That was the beginning of the collapse of Haftar’s house of cards,” said one GNA military official in Tripoli about Haftar’s loss of the town on 5 June.

“It was the main factor that led to Haftar’s forces withdrawal from the other places,” he added.

Haftar’s Libyan Arab Armed Forces (LAAF), now beating a hasty retreat hundreds of kilometres down the coast from Tripoli, deny any foreign fighters exist among its ranks. In interviews with The Independent, its commanders have repeatedly dismissed these allegations as “propaganda” and “lies spread by the GNA and terrorists”.

But UN investigators believe at least 1,200 Russians were hired by shadowy Russian private military companies like Wagner to help Haftar win his war against the GNA.

What caused hundreds of them to withdraw at such a crucial moment is the talk of the town back in Tripoli. Rumours abound of a last-minute deal struck between Ankara and Moscow to allow the mercenaries to exit the frontline unscathed, preventing a potentially deadly confrontation between the two world powers.

“Given the impact on the morale of Haftar’s soldiers, the withdrawal made us feel for sure there was a deal,” said one Syrian mercenary with the GNA.

“All the resistance we faced on all fronts vanished in one night.”

The concluding episode of Haftar’s disastrous attempt to take Tripoli is an illuminating snapshot of how mercenaries have steered victories and defeats in the latest chapter of Libya’s messy civil war.

With wealthy foreign patrons and thousands of soldiers-for-hire deployed on both sides, what was once skirmishes between squabbling fiefdoms of militias has morphed into the world’s newest proxy war.

It has altered the landscape of the country forever and set world super powers including Turkey, Russia, and the United Arab Emirates, against each other.

As one senior diplomat, involved in trying to enforce the UN’s arms embargo, put it: “Libya is the new Syria” – but this time on Europe’s doorstep.

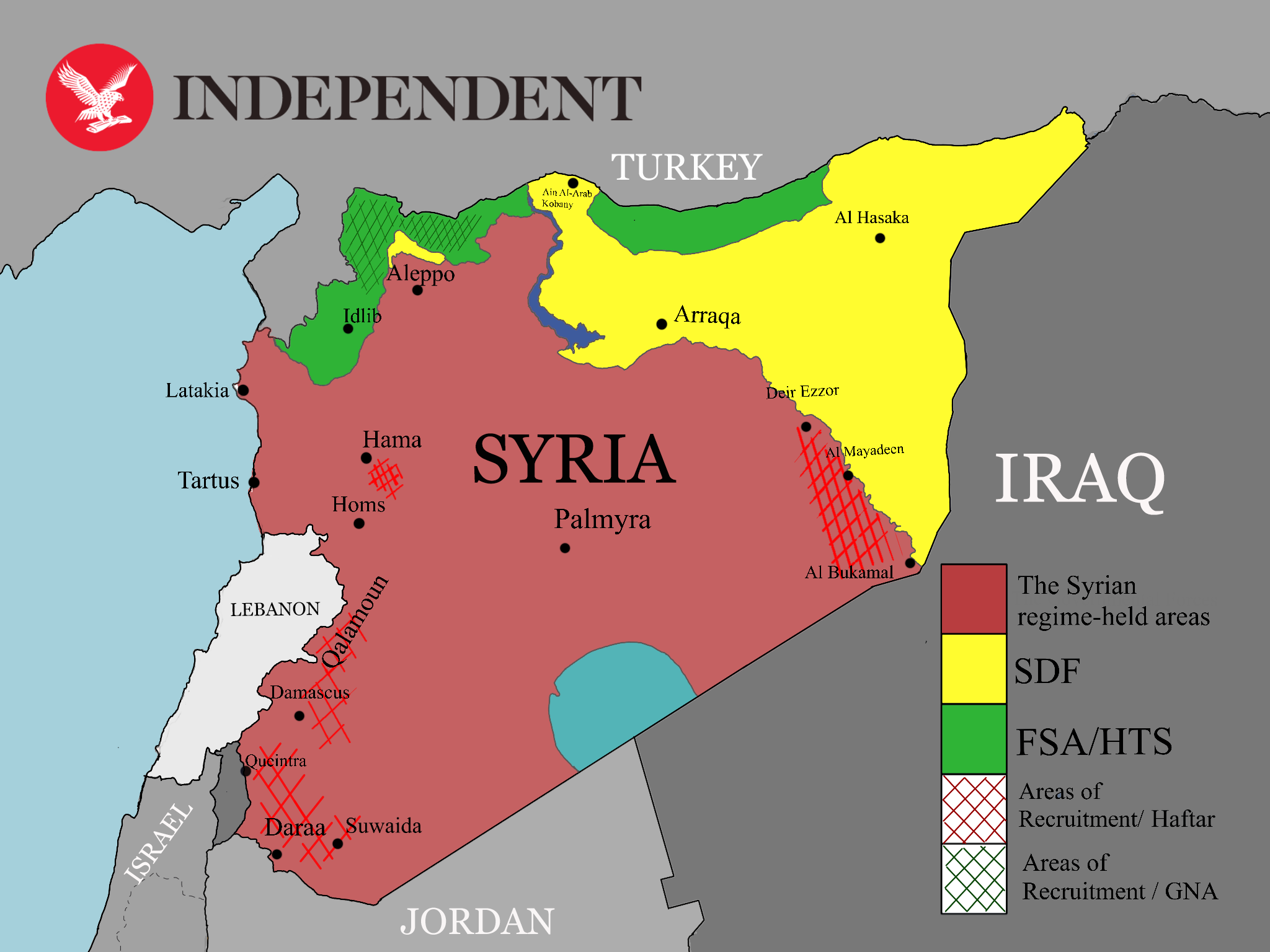

A month-long investigation by The Independent into this murky mercenary underworld shows a labyrinth of recruitment stretching from Moscow to Damascus from Idlib to Istanbul.

Interviews with western diplomats briefed on an ongoing UN probe into arms embargo violations, US military officials, Syrian and Libyan combatants, as well as over a dozen interviews with people across both countries, show the utilisation of the poorest Syrians at the heart of it.

Hired to fight on both sides in Libya, Syrians are once again battling each other – but this time over someone else’s war-wrecked capital thousands of kilometres from home.

April is the cruellest month

Last Spring, things in Libya were looking up.

The UN had scheduled a peace conference in the country’s stunning desert city of Ghadames.

The latest bouts of fighting had shuddered to a halt. In January of that year, police officers from the country’s rival governments had even met in Benghazi to discuss cooperation.

But in April, just days before the peace talks were due to start, the veneer of progress came crashing down. Backed by Emirati air power and later Russian boots on the ground, Haftar launched his ill-fated offensive to oust the Turkish-supported government from Tripoli.

Haftar, nominally linked to a rival administration in the east, has long rejected the GNA as being puppeted by Islamist groups like the Muslim Brotherhood, which he and his foreign backers, including Egypt and the UAE, deem to be terrorists.

The GNA, which is recognised by the UN but guarded by brigades of often unsavoury militias, has the support of countries including Turkey and Italy. It regards Haftar as a war criminal who would be king.

Increasingly alarmed, the UN has repeatedly and futilely warned that the flood of fighters and weaponry into Libya violates a UN arms embargo. The UN’s acting Libya envoy last month pleaded with the Security Council to stop “a massive influx of weaponry, equipment and mercenaries”.

It is hard to keep up with the tapestry of foreign operatives fighting for scraps of the country that has limped through multiple conflicts over the nine years since Muammar Gaddafi was killed next to a storm drain.

Territory is not measured in metres-squared but in footholds of influence across the region that can be played off each other. For the mercenary companies – like Russia’s infamous Wagner group – Libya is a seemingly bottomless purse.

Haftar started the war on Tripoli in April 2019 with the upper hand, making quick gains with powerful Wing Loong II drones, fighter jets and Pantsir defence systems that western diplomats believe were provided by the UAE and later Russia. Both countries repeatedly deny any allegations of involvement in the war.

On the ground the general’s forces were swelled by an injection of mercenaries, which a UN-commissioned probe says included some 1,200 Russian mercenaries and up to 2,000 Syrian fighters recruited from regime areas of Syria. (The Independent’s own investigation put the number of Syrians at closer to 800).

International diplomats briefed on the UN investigation told The Independent an additional contingent of over 2,000 Sudanese fighters, many of whom arrived during a surge of recruitment in November, also gave Haftar an edge.

But the tide turned with Turkey’s formal entry into the foray that was approved by the Turkish parliament in January despite it being a violation of the arms embargo.

“One of the things Turkey did by officially intervening in Libya is upgrade the weaponry. It’s like they fast-forwarded Libya a new generation,” Oded Berkowitz, deputy chief intelligence officer at Max Security, told The Independent.

Ankara not only deployed a few hundred of its own forces, but sent Bayraktar TB2 drones, Korkut air defence systems and – according to western military observers – at least three Gabya-class frigates, creating a vital air defence bubble protecting Tripoli and neighbouring Misrata.

At the same time, UN investigators estimate that Ankara recruited as many as 3,000 of its Turkish-backed Syrian combatants for Libya’s frontline.

Syrian fighters in Libya, however, told The Independent that the true number was closer to 6,000, due to a surge in recruitment over the last two months.

Even the arrival of the coronavirus pandemic in March did not slow the transfer of troops.

Sources on Syria’s border with Turkey told The Independent hundreds of Syrian fighters had crossed over, ready to be deployed to Tripoli this week. Although with the collapse of Haftar’s strongholds, that may not be necessary now.

On Haftar’s side, The Independent was able to confirm a surge in recruitment of pro-regime Syrian mercenaries up until at least mid-May.

Down in the southern desert of Murzuq, along the main smuggling routes from Libya’s porous border desert with Sudan, Libyan residents told The Independent Sudanese fighters in pick-up trucks were tearing their way through the desert to the front lines.

“There is regular movement since the borders are basically open. We have one car, or two, each week crossing the borders,” said one man called Mohamed.

A long way from home

Sitting hunched over his phone amid the pock-marked moonscapes of the Tripoli frontline, Abu Ahmed admitted Turkey’s Syrian mercenaries are miserable.

“Some are so desperate to go home, they shot themselves in the legs so they can get airlifted out,” the battle ravaged ex-rebel said.

Some are so desperate to go home, they shot themselves in the legs so they can get airlifted out

Like most of the Syrians he knows, the 27-year-old says he only agreed to fight in Libya because he assumed it was easy to catch a migrant boat to Europe. “It turns out it’s not,” he added bitterly. “All of the Syrians here for a long time advise: don’t trust anyone and just try to get home.”

After years fighting with rebel factions against Syrian regime forces, Abu Ahmed joined the Turkey-backed Syrian National Army last year as it spearheaded Ankara’s incursion into Kurdish-held northern Syria.

He was first deployed to Tripoli on the GNA side in February 2020. Over the last month of messaging The Independent his mood has gone from bad to worse.

He described how the Syrians’ unruly behaviour – including looting, and stealing weapons – has angered several Libyan brigades, worried about the optics of foreigners fighting their battles. He recalled how one Syrian friend captured a Syrian on the rival side, painting a poignant vignette of the pointlessness of it all.

“Here in Libya they treat us like if we were a sack of money. The Libyans hate us and don’t trust us at all. We just want to go home,” he continued.

Abu Ahmed’s story echoes thousands of other Syrians caught up in the region’s proxy wars. He was just 17 and working in his parent’s shop when the Syria civil war broke out in 2011. He never finished secondary school and so nine years later, to survive, he fights for whoever will pay the most.

That ended up being the GNA, which, with Turkish support, was promising $2,000 a month for four months: a considerable pay rise from his monthly salary of 500 Turkish lira ($70) fighting Turkey’s offensives in northern Syria.

In fact Ankara entrusted top commanders of the Turkish-backed Syrian brigades with their recruitment drive. According to multiple fighters in Libya and civilians in northwest Syria the likes of Fehim Isa, who leads Sultan Murad brigade and “Abu Amsha”, from Suleiman Shah, have done lucrative stints in Libya with their men.

The journey from northeast Syria to Tripoli takes roughly one week. Abu Ahmed described crossing the Hawar Kilis border point, boarding military aircraft from the southern Turkish town of Gaziantep to Istanbul and then flying commercial onwards to west Libya.

Another GNA fighter, who was among the first dispatched in January and is back in Syria, told The Independent the Syrians he was fighting alongside were quickly disillusioned. Even the money promised was not that good.

Omar (not his real name) explains $200 of their monthly salary is siphoned off to their brigade. “The situation in Libya is like in Syria, we fight without any planning,“ Omar added, describing mutinies among the Syrian factions, absent battle strategies and frosty welcomes from disgruntled Libyan militiamen.

“Some Syrians were so depressed they threatened that if they weren’t sent home they’d kill anyone standing in their face.”

He said the Syrians cannot escape home by themselves as it requires transiting through Turkey and so the approval of their commanders.

This disgruntlement began to filter back through the ranks to Syria. A well-placed international diplomat told The Independent the GNA was originally promised up to 9000 fighters but had “recruiting challenges”.

Back in Syria, one man from Afrin, a town on the Syria-Turkey border, said that recruiters, finding it increasingly hard to sign up fighters, targeted civilians. He was approached to help recruit from IDP camps.

“I was offered 200$ for each civilian I could recruit to Libya. It is difficult getting fighters who want to go to Libya,” he told The Independent.

Fighting to feed yourself

Despite these difficulties, by May, Haftar would realise he was losing the war.

In the weeks before, it was already apparent that Turkey’s fraught recruitment efforts were translating into military successes. With GNA forces recapturing territory, Haftar’s international backers also looked to Syria to plug a manpower shortfall.

Libya’s eastern administration linked to Haftar even opened an embassy in Damascus in March, announcing they would fight Turkey-backed militant groups together with Syrian president Bashar al-Assad.

And so, as Abu Ahmed was busy signing up in Idlib near Turkey’s border in February, hundreds of kilometres south in the regime-held areas of Douma, Daraa and Suweida, Kremlin-linked private military companies sent recruiters to villages to convince young men to join Haftar’s side.

UN experts, investigating arms embargo violations, believe that between 1 January and 10 March there were 33 Cham Wings flights from Damascus to Benghazi, likely transporting Syrian mercenaries. (The Syrian airline was sanctioned by the US in 2016 for providing financial support to the Assad regime and transporting Syrian troops.)

The same UN probe said in January this year Russian recruiters were first sent to Douma offering $800 a month. With little pick up, the salaries promised were increased to over $1000 and recruiters moved to a small pocket in Suweida, a centre of Syria’s Druze religious minority.

In March, recruiters shifted their focus to Daraa, a region close to Syria’s border with Jordan. There, according to three people whose friends and family were approached to sign up, they started tapping into brigades of reconciled ex-rebels that made up a special branch of the “Fifth Assault Corps” one of the premier Russian-backed formations in Syria.

These young men were easier to convince. Ex-rebels who pledge allegiance to Assad typically earn less than $30 a month as regime soldiers.

They are often harassed by regime security forces who are distrustful of them and so impose harsh restrictions on the jobs they can secure and their movement.

Omran Musalmah, a Syrian activist from Daraa, who is in close contact with villages targeted by the recruitment drive, said Wagner-organised recruiters not only promised to pay the reconciled fighters $1,200 a month, but to stop that harassment.

“They were told the mission would be securing oil fields and Russian facilities. If they agreed, the security forces would stop the abuse against them,” Musalmah said.

“But when they reached the training camps in Homs they learned they were going to fight with Haftar against the government in Tripoli. Most went home.“

By April, the story repeated itself in Quneitra, an area close to the border with Israel. There Elizabeth Tsurkov, a Syria expert at the Foreign Policy Research Institute who spoke to community members, said the men signed up because their families “were going hungry”.

“This is only happening because of immense need,” Tsurkov told The Independent.

“They have no alternatives”.

As Haftar’s offensive began to stall his recruiters ramped up their efforts.

By June, he lost the strategic Wattiya airbase, at least nine multimillion-dollar defence systems and Tarhuna, his chief re-supply line.

In the weeks prior, Russian recruiters trawled Syria’s southern Hama countryside, areas of neighbouring Homs, as well as the eastern province of Deir Ezzor, according to local sources.

The process was fraught. In southern Hama, residents of villages told The Independent it took a month to convince anyone to sign up.

“A hundred eventually made it to Khmeimim, [Russia’s main airbase in Syria] on 8 May ready to be deployed to Libya days later,” said one man, whose family still lives in the area. He asked to remain anonymous.

The Independent was told by multiple sources they likely boarded a 11 May Cham Wings flight from Khmeimim airbase in Latakia to east Libya.

Maritime observer Yoruk Isik, who tracks Cham Wings flights between the two countries using open source software, watched that particular flight with interest.

He told The Independent it was one of the first and only times Cham Wings had left a transponder along that route. The planes usually vanish from tracking apps above Benghazi.

But this time the plane quietly descended on Khadim – an east Libyan base UN investigators claim was set up by the UAE . It’s an odd destination for a commercial airline.

Little is known about exactly where the fighters end up. Diplomats briefed on the UN investigation said as soon as they board planes, after a final phone call back home, their mobiles are confiscated.

On arrival, they are issued “burner” phones – with no access to the internet – so they can communicate with each other but not with the outside world.

Moscow’s mercenary men

On Haftar’s bases across Libya, disagreements are notoriously frequent.

The problem is, one international military observer said, the general has limited foreign advisers that he rarely listens to.

It didn’t help that “he and his staff do not understand modern warfare,” the official added. Tensions between his command and Wagner have reportedly soared.

Russian mercenaries first emerged in east Libya in 2018 repairing military vehicles. Most, including UN investigators, point the finger at Wagner – nicknamed Russia’s Blackwater.

But Neil Hauer, an independent expert on the group, said Wagner is actually a catchall phrase for a number of “nebulous arms-length private military companies” that have emerged over the last few years with ties to Russia’s Ministry of Defence.

Wagner was created in 2014 during Russia’s war in Ukraine and first deployed in Syria two years later. But it had “its wings clipped” in February 2018 after a messy shoot-out with American forces in Syria upset the Kremlin, according to Hauer and international diplomats.

And so, UN investigators said alongside Wagner multiple smaller private military companies were deployed to Libya.

Whoever is responsible for the recruitment of Russian combatants, they first appeared on the west Libya frontlines in September, according to international diplomats.

Russian identity cards and personal items, apparently left behind during a retreat, were discovered in the battlefields around Tripoli.

At some point the Russia military deployed its own forces to Libya, possibly in advisory roles.

A BBC investigation found that the first Russian commissioned officer died in Libya in February. The 27-year-old soldier was later buried in his Russian hometown in a heavily policed funeral.

The Russian defence ministry did not reply to a request from The Independent for comment.

Russian president Vladimir Putin has vehemently denied the accusations that Russia is funnelling fighters and equipment to Libya. When asked in January about Wagner, he replied that if there are Russians in Libya, they do not represent the Russian state.

But as one western diplomat put it, it is safer to deploy a group like Wagner than the military, “it is a lot of strategy for not many roubles”.

That was echoed by US Africa Command, which confirmed to The Independent Russia has flown a mix of 14 MiG-29 fighters and Su-24 fighter-bombers to Jufrah, Haftar’s main airbase in central Libya.

A spokesperson said Washington believes that Russia was employing Wagner in Libya as part of a Kremlin strategy to “expand its influence across the Mediterranean and the African continent”.

“Russia employs state-sponsored [mercenaries] in at least 16 African countries to obfuscate Moscow’s direct role and to afford plausible deniability,” the spokesperson added.

Who’s paying the bills?

Back in Tripoli, speculation about the Russian mercenary salaries is rife.

“They must get a huge amount,” one GNA fighter wrote on WhatsApp. “Otherwise why would they agree to fight?”

A three-month contract in Libya for all the fighters is estimated to cost nearly $175m, according to UN investigators. No one believes Haftar can finance that on his own.

Some allege Russian businessman Yevgeny Prigozhin, who is nicknamed “Putin’s chef” for his Kremlin catering contracts, is the shadowy financier of Wagner.

Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdogan, meanwhile, has accused Abu Dhabi of bankrolling the enterprise in a fiery speech where he dismissed Haftar as a “desert lord”.

UN investigators have long accused the Emirates of providing material support to Haftar’s forces. As early as 2017 a panel of experts report said the UAE had sent drones, planes, attack helicopters and armoured vehicles to Libya, stationing them at Khadim, an airbase Abu Dhabi built up.

The UAE authorities did not respond to The Independent’s request for comment on Libya. But the Emirates have repeatedly denied funnelling weapons to Libya and maintain they are supporting a “peaceful political solution” to the crisis. Last week they once again rejected claims by the GNA they were involved in Haftar’s military operations.

There were, however, Dubai links to a botched attempt last year by Haftar to hire western mercenaries, including five Brits.

A recent confidential UN probe found that, in the middle of the battle for Tripoli, Haftar paid a team of 20 foreign mercenaries, upwards of $120,000 to create a marine strike force to prevent Turkish-supplied weapons reaching the GNA.

The western soldiers-of-fortune arrived in Libya last June but fell out with Haftar and fled the country by boat just days after they arrived.

Two diplomats briefed on the probe said two Dubai-based companies were named as allegedly masterminding the deals. Both companies denied their involvement in a statement to The Independent.

The future

Whoever is footing the bills, Haftar’s stunning defeat has dealt a crushing blow to his foreign backers who are scrabbling to renegotiate their positions.

“They are quickly realising it is not that easy. Throwing some contractors into the mix will not see Haftar sweep to victory,” said analyst Hauer.

Egypt, which had taken a back seat in Libya, appeared to return to the ring hosting one-sided peace talks in Cairo last weekend. There Haftar agreed to a unilateral ceasefire provided – ironically – the GNA sends its foreign mercenaries home.

This was roundly rejected by the recognised government who instead declared a new offensive to take Sirte and Jufrah airbase, over 500km southeast of Tripoli.

As bloody battles have raged in Sirte, videos have appeared online this week allegedly showing Egyptian military build up along its border with Libya, which some have read as a warning sign to the GNA to back down.

Throwing some contractors into the mix will not see Haftar sweep to victory

Jalel Harchaoui, a Libya expert at the Clingendael Institute, said that under the alleged deal between Ankara and Moscow, Sirte was not supposed to be taken by force. West Libyan forces have marched too far east.

“Cairo is under tremendous pressure on the part of the UAE and to some extent Saudi Arabia to take a firmer stand,” he added.

Cairo, reportedly unhappy about the Tripoli offensive in the first place, is likely waiting for the outcome of the rumoured Turkey-Russia deal.

That may be determined by movement of forces on the ground. Officials within the GNA’s interior ministry told The Independent they would not stop until they had taken Sirte and Jufrah and were even mulling marching on the Haftar-held oil crescent too.

The UN has said that the warring parties had agreed to restart ceasefire talks but ongoing fighting undermines that.

Trapped in the middle are the mercenaries. Fresh Syrian recruits for the GNA’s new offensive are due to land early this week, according to multiple sources.

Syria was killing me, Libya was the only way out

Abu Ahmed’s fighting contract, however, is due to end in the coming days.

Over the last month he has come full circle and is now debating whether to stay in Libya where there are better chances of finding a job than in Syria, ravaged by a crushing financial crisis. It is also easier and cheaper to get to Europe from Libyan shores.

“Syria was killing me, I needed to leave in any way possible but had no chances. Libya was the only way out,” he says his voice thick with regret.

“My only thought about coming here was that I could make some money and cross the sea to Italy which I still want to do.”

“Europe is my only hope.”

Read the first part of the Soldiers of Misfortune series here: Libya’s beleaguered general Haftar swindled out of millions by western mercenaries and businessmen

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments