Kenya still haunted by murder of Catholic priest 15 years ago as Pope Francis arrives as part of African tour

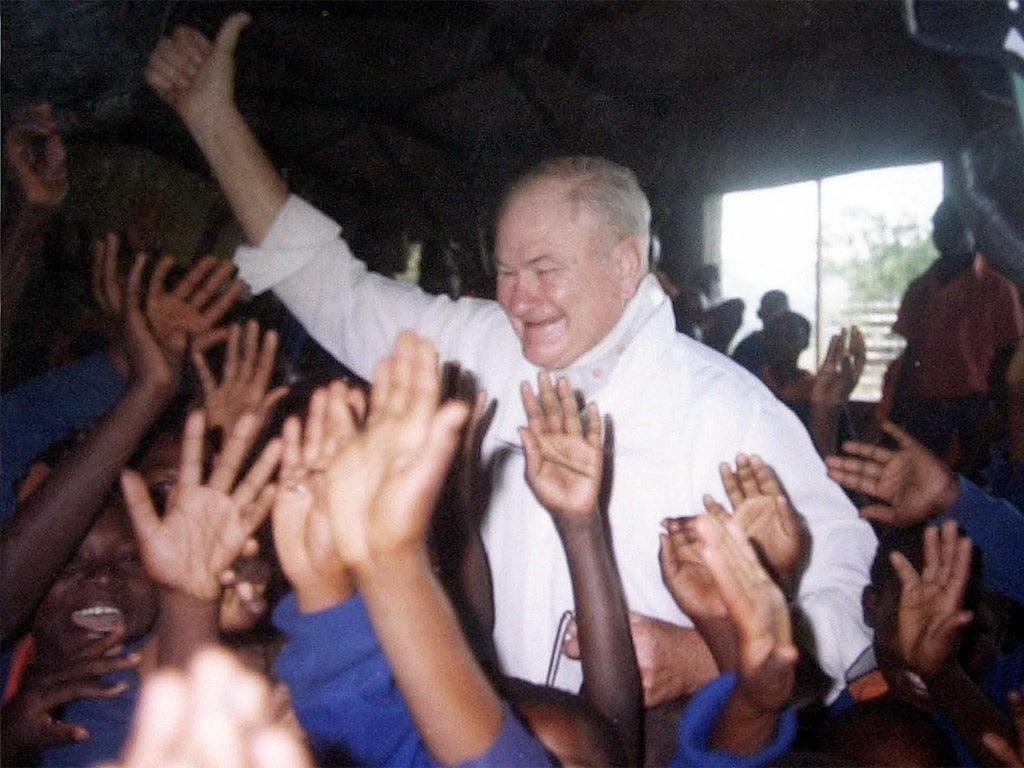

US-born missionary Father John Kaiser - an outspoken critic of the government of President Daniel arap Moi - was found in a ditch with a gunshot wound to the back of his head, and some believe the Church has failed to take a stand in the search for justice

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.His office tucked away in a shabby block just yards from one of Nairobi’s busiest thoroughfares, Mbuthi Gathenji, a bespectacled lawyer in his 50s, has spent the best part of a decade trying to unravel a complex web of political intrigue in Kenya that lies at the heart of the murder of a troublesome Catholic priest.

Fifteen years after Father John Kaiser, a US-born missionary, was found in a ditch, blood still oozing from a gunshot wound to the back of his head, Mr Gathenji is still struggling to get justice for the man who campaigned for the voiceless and was a thorn in the side of the government.

As Pope Francis arrives in Nairobi on Wednesday, on the first leg of an African tour that will take in Uganda and the Central African Republic, the incident continues to haunt Kenya’s Catholic Church, which once positioned itself as the conscience of the nation but is now, some argue, a moral force in decline.

Appealing to the Pope to put pressure on the Kenyans to reopen the case, Mr Gathenji said it was time for the Church to “show leadership”. “Why is Fr Kaiser’s murder not being followed up?” he asked. “Why is there nobody strong enough to say ‘this has taken too long’? Witnesses are dying, memories are fading.”

It was a little after dawn when a butcher, on his way to market along the Naivasha-Nakuru highway, came across a white man, his head blown away, a shotgun by his side.

The man was quickly identified as Fr Kaiser, 67, an outspoken critic of the government. Born in Minnesota, he came to Kenya as a simple parish priest, but he took on a more political role when he was sent in 1993 to Maela refugee camp, sheltering Kenyans ousted from their homes in fierce clashes after elections the previous year. He accused the government, including President Daniel arap Moi, of inciting the violence as part of a land grab.

More immediately, he was helping two young girls bring a rape case against a young politician and one of Mr Moi’s most trusted advisers, Julius Sunkuli. It was, said Mr Gathenji, just the beginning. Fifteen women in all would come forward – although Mr Sunkuli faced only the two rape charges, which he denied and were later dropped.

Few doubted it was an assassination. “You could see he was going to be killed,” said Mr Gathenji, who became friends with the priest in the years before his death. “Death was always near if you were against Moi or any of his ministers.”

In the last hours of his life, the missionary appeared edgy, scared for his life, according to friends. Detectives from the FBI, called in to lend credibility to the investigation into his death, would later make much of his disturbed state and declare it suicide.

But those who knew him challenged it: Kenya, after all, had a history of assassinations disguised as accidents. Before his death, the priest wrote that he would be murdered. “I want all to know that if I disappear from the scene, because the bush is vast and hyenas many, that I am not planning any accident, nor, God forbid, any self-destruction,” he wrote.

Independent post-mortems concluded that the shot was fired from three feet away, an impossible feat for the priest to have carried out.

It was only when Mwai Kibaki was swept into power in 2002 that the Church was able to challenge the suicide findings and demand an inquest. In 2007, a magistrate ruled it murder, and ordered an investigation into four named suspects. Mr Sunkuli, who denied having a motive to kill Fr Kaiser, was not one of them.

The investigation never took place. The Church believes this was because the office of public prosecution was, and is, headed by Keriako Tobiko, the lawyer who represented Mr Sunkuli at the inquest. “It’s likely he is going slow because he was the lawyer and is now the prosecutor,” said Bishop Philip Anyolo, head of the Kenya Conference of Catholic Bishops. “We want to take it further. It’s a case that should be brought to a conclusion.” The prosecutor’s office did not respond to request for comment.

Fr Kaiser’s former colleagues at St Joseph’s Missionary Society of Mill Hill (formerly London-based, now in Maidenhead, Berkshire) have abandoned their own efforts to push for an investigation. “If the political will is not there, you’re fighting a losing battle,” said one missionary, who asked not to be identified for security reasons.

Critics say that is defeatist talk, considering that churches campaigned against the brutal excesses of the Moi regime and were instrumental in bringing about multi-party rule in 1992.

When Mr Kibaki, a practising Catholic, took power, the Church relinquished its role as critic of the government. “There was a sense of ‘job done’,” said Ben Knighton, a lecturer at the Oxford Centre for Mission Studies. Kibaki’s election, he said, “was regarded as a great victory for the Roman Catholics. They have been on the government’s side ever since”.

Now both Catholic and Protestant churches have lost much of their moral authority, he said, because neither had taken a firm stand since then “against abuse of power”.

The Vatican declined to comment, but Catholic officials expressed doubt that the Pope would single out Fr Kaiser’s case during his visit. Nevertheless, he is expected to call for reconciliation in a country blighted by tribal tensions and Islamist extremism. His message is a powerful counterweight to what critics say is an increasingly partisan Catholic Church in Kenya that did not call to account the perpetrators of the ethnically charged post-election violence in 2007-08, and campaigned against Kenya’s landmark new constitution.

Even when the Catholic church was at its most outspoken, Mr Gathenji says that Fr Kaiser cut a lonely figure. “He would always say: ‘I’m alone in what I’m doing. My colleagues are afraid’,” he recalled. They would urge him not to provoke Moi, to drop his opposition to the state. “But Fr Kaiser would reply: ‘Then who else?’”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments