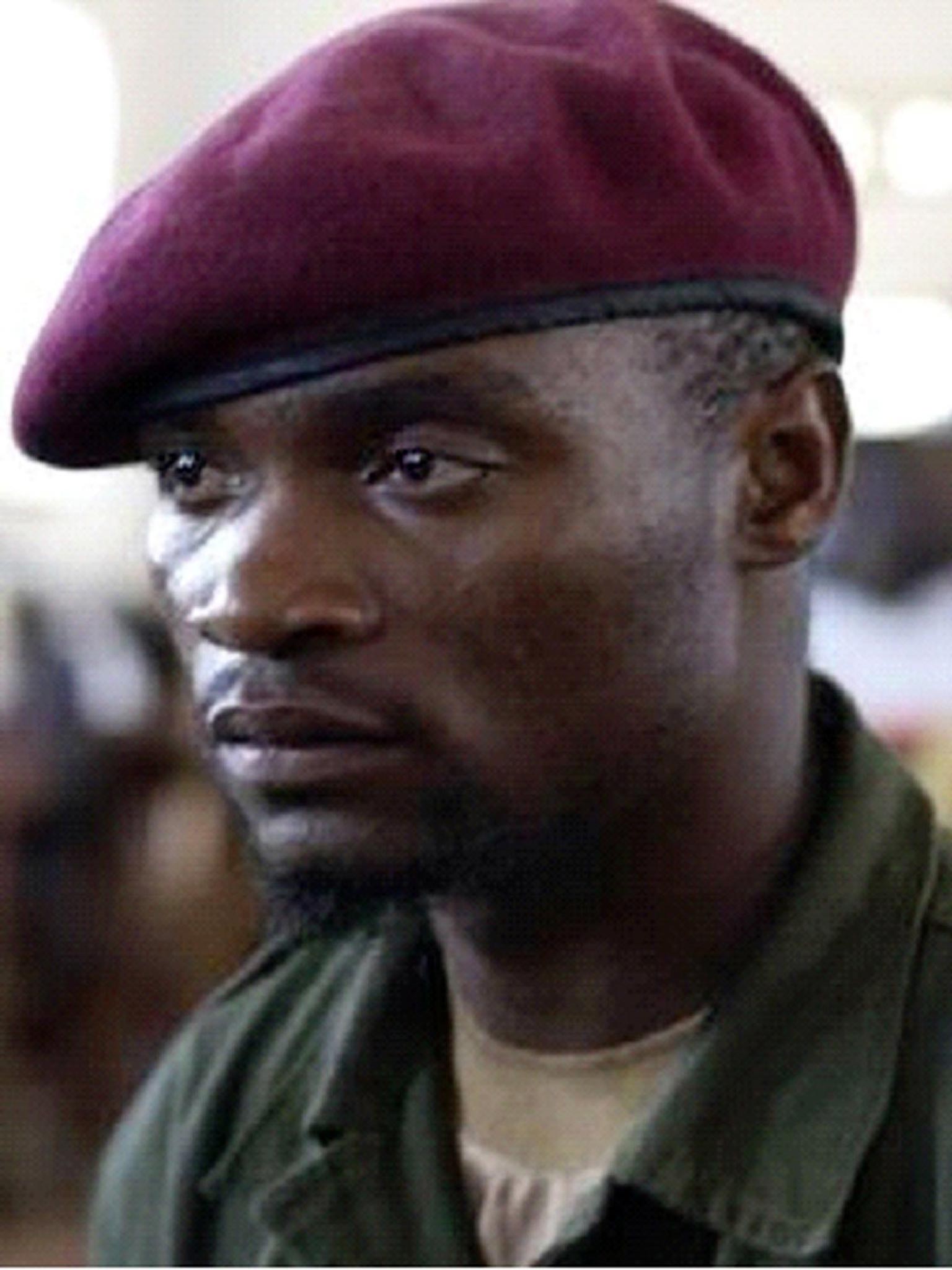

Germain Katanga: Guilty of war crimes, the brutal warlord who terrorised the Democratic Republic of Congo

Steve Crawshaw reports from The Hague on a landmark moment for the International Criminal Court

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The former warlord once known as “Simba” rose to his feet at the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague, at the end of an hour-long summary of the charges and findings against him.

Germain Katanga stood impassive and motionless as the judge read the final judgment summary, where he was pronounced guilty on five counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Today’s judgment marked a small moment of history. It was only the second conviction since the ICC was created 12 years ago and comes at a time when the court is under greater pressure than ever before.

Katanga was a militia leader in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where millions died in the war in the east of the country. The crimes he has been convicted of relate to a massacre in the village of Bogoro in 2003.

The court heard vivid descriptions of the horror, as “part of an operation to wipe out the civilian population”.

Today’s judgment emphasised that rape and sexual slavery, documented by the prosecution, amounting to war crimes and crimes against humanity had occurred – but found insufficient evidence to link Katanga directly to those crimes.

More than 300 victims participated in the case and the judge yesterday paid tribute to some of them individually because of their important contribution. (The witnesses were named by registration numbers only because of the risks they still face.)

As in many other conflicts around the world, perpetrators in the DRC felt confident they would never face justice. Eight years ago, I visited the site of another massacre which was also blamed on militias linked to Katanga. More than 1,200 died in Nyakunde during a killing spree which lasted for days. Fourteen people hid in the ceiling of the hospital operating room, until the killers found them there.

Four years after that massacre, the psychological wounds were raw. As I reported in an article for The Independent at that time, the Mayor talked of aspirations for killers to be held to account: “It is important that they should be judged and brought to justice so that this can’t happen again.”

But if victims have welcomed the ICC, some African governments have become critical, now that the court has begun to show its strength.

African governments played a key role in the formation of the court. But the argument that this is an “anti-African” court is widely heard. Certainly, all the cases now before the court come from Africa, not least because of the failure of the UN Security Council to refer other situations, like Syria, to the court.

An arrest warrant has been issued for Joseph Kony, in connection with the crimes of the Lord’s Resistance Army in northern Uganda. Laurent Gbagbo, the former President of Ivory Coast, is now in pre-trial detention in The Hague, in a case referred to the court by the Ivorian government. President Omar al-Bashir of Sudan, still in power in Khartoum, has been charged with genocide in Darfur.

Most notably, the court has charged Kenyan leaders, including President Uhuru Kenyatta and his deputy (and former opponent) William Ruto in connection with violence in the aftermath of the Kenyan elections of 2007, which cost more than 1,200 lives. Kenya has threatened to withdraw from the court itself. For its opponents, the ICC is “imperial” in its vision. Leaving aside the fact that the chief prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, is Gambian, the Court’s role is to bring to justice those who have committed war crimes and crimes against humanity against their fellow citizens – hardly an imperial aspiration.

For those most directly affected by the crimes of Katanga, the court can help bring closure, which until a few years ago seemed unachievable.

In eastern Congo, the leader of a local human-rights organisation – who has received death threats because of his work for justice – told me in 2006, in words that remain relevant today: “People are forced to choose between peace and justice. But you can’t have peace without justice. The people who are dead are dead. But if you try to compromise peace for justice, that doesn’t help.”

One Congolese activist said today, in response to the news from The Hague: “For those who lost their possessions, their mothers, their homes, this judgment provides some relief. Today people here see some satisfaction. In the end, everyone must answer for his actions.”

Steve Crawshaw is director of the Office of the Secretary General at Amnesty International

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments