How the British Empire's gay rights legacy is still killing people to this day

"For the most part, the criminalisation of homosexuality in Africa is a direct result of colonialism"

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

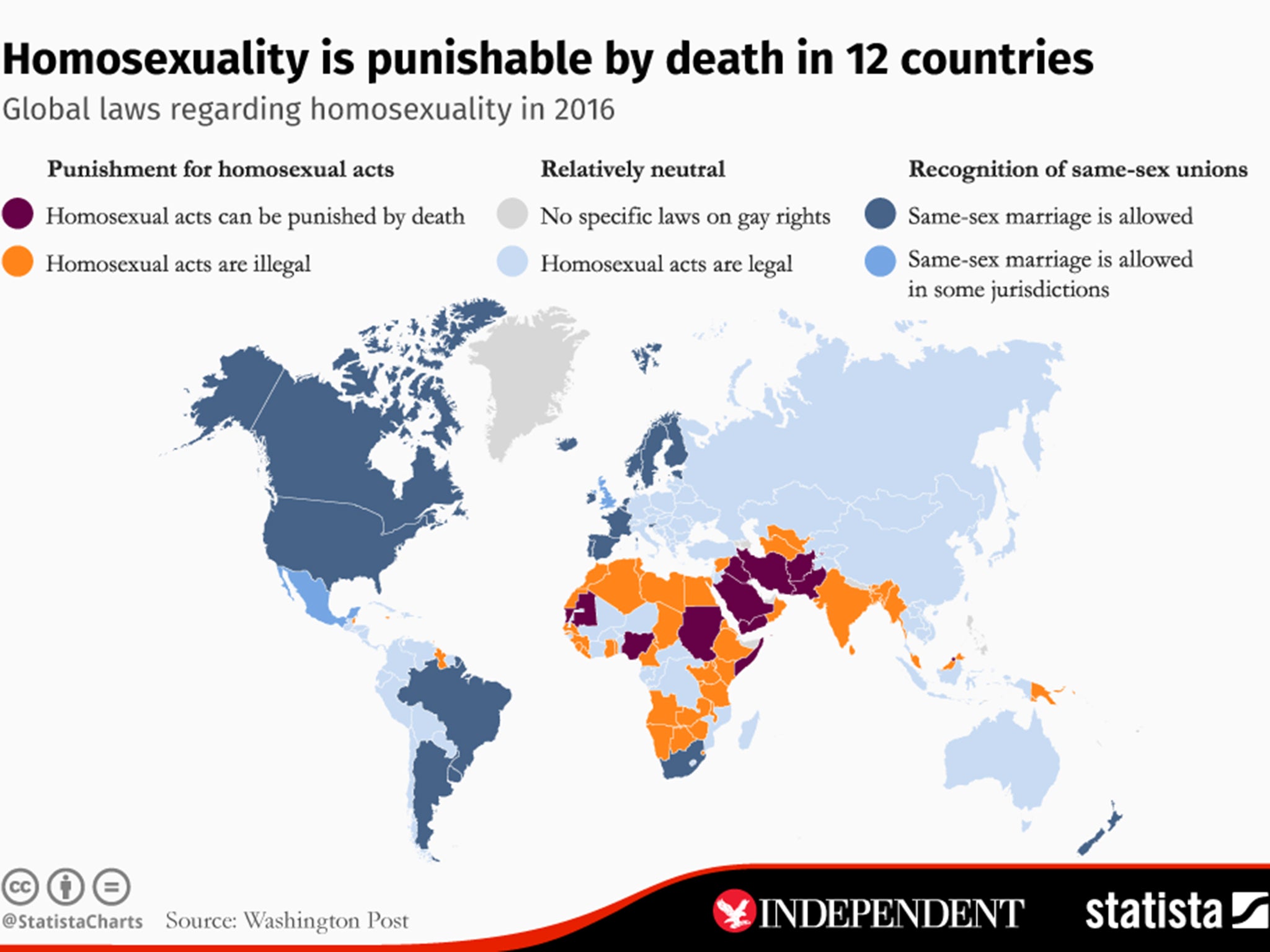

Your support makes all the difference.Homosexuality is illegal in 34 of Africa's 56 states. In Mauritania and parts of Nigeria it’s a crime punishable by death and in states such as Gambia, Sierra Leone and Tanzania it could mean up to life imprisonment. Only a handful of states have in place anti-discrimination laws protecting LGBT people. Same-sex marriage, legal only in South Africa, has been constitutionally banned by eight states.

For the most part, the criminalisation of homosexuality in Africa is a direct result of colonialism, with much of the anti-homosexual legislation introduced by European states still in place. But recently, political pandering and religious influence have seen countries such as Gambia and Nigeria introduce laws which further restrict the human rights of their LGBT populations.

The situation has garnered the attention of the Western media and, when President Obama made his historic trip to Africa in July last year, he called on the continent’s leaders to offer better protection to their LGBT citizens. Though an admirable interjection, his ability to talk openly about homosexuality in Africa, without fear of repercussion, is something of a privilege. Freedom of expression and freedom of association are integral in the fight for LGBT acceptance, but in many African states (and beyond) these fundamental human rights are heavily restricted.

The above article was created for The Independent by Statista

Before the continent’s activists can bring about the decriminalisation of homosexuality, they must first secure a platform for discussing the issue free from persecution. In countries like Uganda, that particular challenge is set to become much harder.

Though Uganda’s infamous Anti-Homosexuality Act (AHA) was nullified in early 2015, a new bill designed to stifle non-governmental organisations (NGO) operating across the country is set to come into law. The legislation will require NGOs to acquire government issued permits in order to operate. While the law is not a specific attack on the country’s LGBT population, they’re certainly a high profile target. For Dr Frank Mughisha, the country’s most high profile LGBT activist, it threatens the existence of his organisation, Sexual Minorities of Uganda (SMUG).

“Any organisation that's not in the public interest cannot exist, any organisation that is not a registered NGO cannot exist,” says Dr Frank Mugisha. “It will definitely affect a lot of other countries as well because many countries, including the UK, are providing development support to many NGOs in Uganda and some of those NGOs are also doing work on LGBT rights. So they'll be shut down.”

Despite the repeal of AHA, LGBT Ugandans still face persecution from local police forces, which carry out the arrests of those they perceive to be LGBT. While in custody, many of those arrested have been exposed to egregious human rights violations.

“What they do is carry out these very degrading examinations, to ascertain if someone had penetrative sex,” says Mugisha. “They do it with almost every suspect. They've told us that it's the only way to prove if someone had anal sex or not. So there are so many vulnerable LGBT people who get arrested by the police who go through all this ordeal without having proper representation.” If the latest NGO bill comes into play, as is expected, Mugisha’s SMUG will be unable to operate and even fewer will secure representation when they need it.

Botswana still has the anachronistic colonial laws which criminalise same-sex sexual activity in place. But, as is the case with many states across the continent, these aren’t actually enforced. There is even legislation in place protecting LGBT people in employment.

Despite this the country’s primary LGBT organisation, LEGABIBO (Lesbians, Gays and Bisexuals of Botswana), has had to take the government to court in order to secure the necessary registration to operate. Though a judge ruled that the government had been unconstitutional in rejecting the group’s administration, the decision was appealed.

“The reason why they refused to register us is that we are promoting actions that are illegal,” says Anna Chalmers, coordinator for LEGABIBO. “The government is not yet ready to openly say ‘yes LGBT can associate here’. The push to appeal our win at the higher court came directly from the cabinet, so there's quite a lot of opposition from the high places as well as from the society as well.”

With the case still ongoing, it’s indicative of how securing total freedom of expression is the first hurdle LGBT activists must clear in the struggle for greater equality. And while country’s like Uganda and Nigeria are restricting freedoms, elsewhere the green shoots of progress are starting to show.

In April last year, Kenyan activist Eric Gitari won his challenge against the government, with the Kenyan high court ruling that attempts to block LGBT groups from registering were unlawful.

“It was a first step towards recognition of the existence of sexual and gender minorities,” he says. “We felt there was need for the state to recognise our existence in the first place. We started seeking registration as early as 2012 and we were rejected six times. We noticed what was very consistent in all the rejections was that they were underlining or circling the words gay and lesbian in the proposed organisations name.” Gitari’s organisation, the National Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission, is now an officially registered charity.

In what could prove to be a similarly significant case, last year an activist in Zambia was acquitted by the national courts after he was originally charged for speaking about the need to recognise the rights of LGBT people on national TV. It could prove to be a landmark decision for human rights activists across the country.

“Even though same sex acts are criminalised it's not an offence to lobby for the decriminalisation of those acts,” says Anneke Meerkotter, litigation director at the Southern Africa Litigation Centre. “We’re trying to get the courts to very gradually make positive statements so that one day you can take a case to court specifically around getting rid of the offences themselves. For us the issue is more around looking at what you can win. And what you can win is arguments around freedom of association and freedom of expression.”

Despite signs of progress, LGBT people are still actively persecuted across the continent. As activists celebrate recent pro-LGBT court decisions in Botswana, Kenya and Zambia, those in Uganda, Nigeria and Gambia fear even further persecution, both from the government and society. For the LGBT populations living in these regions, ensuring they still have the space to speak about the issue and challenge criminalisation is essential.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments