Ebola outbreak: 'Plague villages' set up to contain virus emulate methods of medieval Europe

Emergency measures implemented include medical roadblocks similar to those used against Black Death

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The rapid spread of Ebola has led to affected countries creating quarantined villages, medical roadblocks to halt the spread of the infection to cities, and military operations forcing people ill with the disease to stay in their homes, creating a modern-day version of the “Plague villages” created in medieval Europe, and demonstrating the extent of West Africa’s suffering under the outbreak.

Liberia has quarantined remote villages at the epicentre of the virus in an effort control the epidemic, shutting them off from outside world and evoking the medieval methods deployed to deal with disease hundreds of years ago.

With few food and medical supplies getting in, many abandoned villagers face a stark choice: stay where they are and risk death or skip quarantine, spreading the infection further in a country ill-equipped to cope.

In Boya, in northern Liberia's Lofa County, Joseph Gbembo, who caught Ebola and survived, says he is struggling to raise 10 children under five years old and support five widows after nine members of his family were killed by the virus.

Fearful of catching Ebola themselves, the 30-year-old's neighbours refuse to speak with him and blame him for bringing the virus to the village.

"I am lonely," he said. "Nobody will talk to me and people run away from me." He says he has received no food or health care for the children and no help from government officials.

Aid workers say that if support does not arrive soon, locals in villages like Boya, where the undergrowth is already spreading among the houses, will simply disappear down jungle footpaths.

"If sufficient medication, food and water are not in place, the community will force their way out to fetch food and this could lead to further spread of the virus," said Tarnue Karbbar, a worker for charity Plan International based in Lofa County.

Ebola has killed at least 1,145 people in four African nations, but in the week through to August 13, Lofa county recorded more new cases than anywhere else - 124 new cases of Ebola and 60 deaths.

The World Health Organization and Liberian officials have warned that, with little access by healthcare workers to the remote areas hidden deep in rugged jungle zones, the actual toll may be far higher.

In the ramshackle coastal capital Monrovia, which still bears the scars of the brutal 14-year civil war that ended in 2003, officials say controlling the situation in Lofa is crucial to overcoming the country's biggest crisis since the conflict.

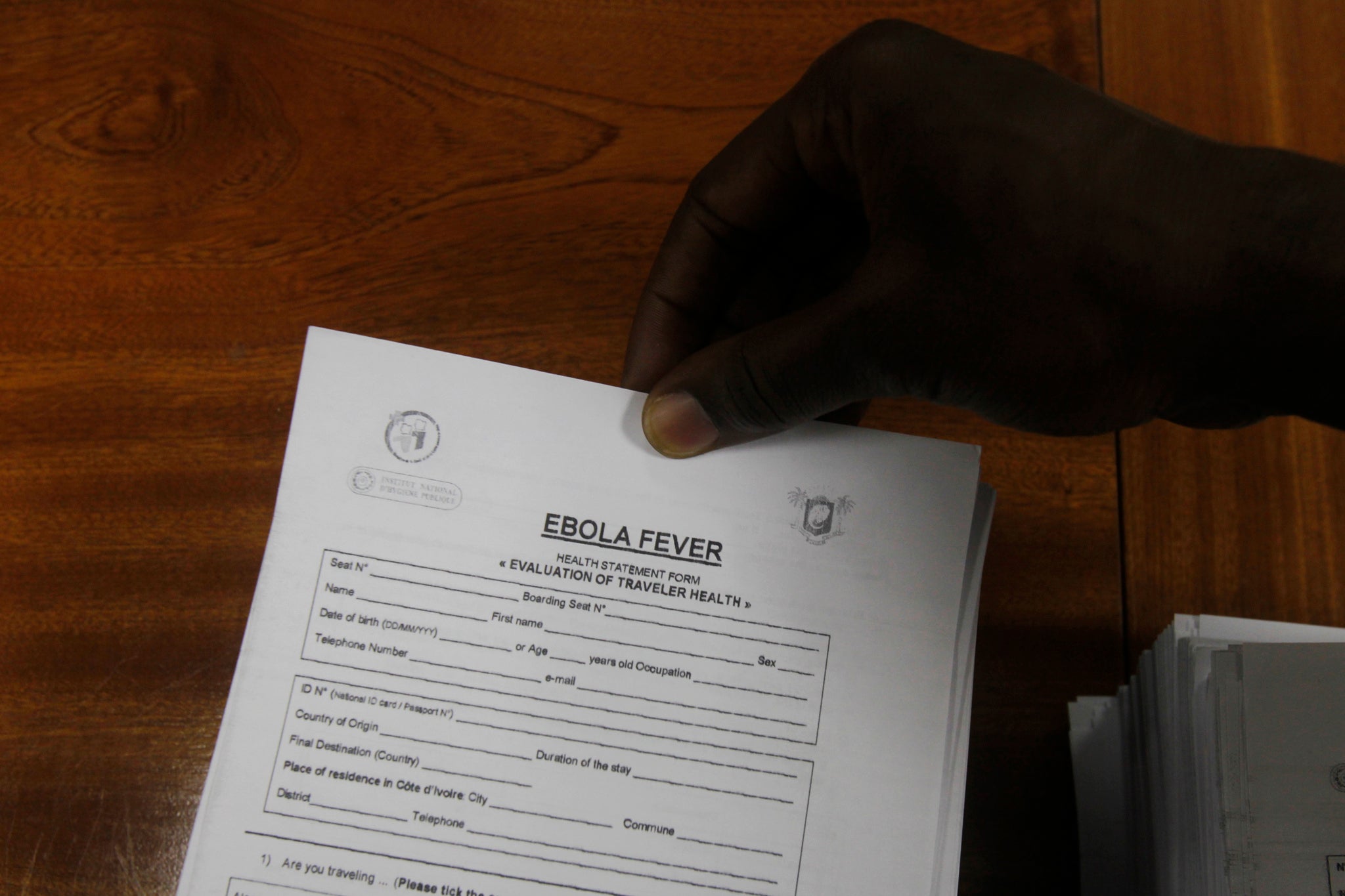

With her country under threat, President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf has imposed emergency measures including the community quarantine and a "cordon sanitaire" -- a system of medical roadblocks to prevent the infection reaching cities, widely used against the Black Death in Medieval times.

Troops have been deployed under operation "White Shield" to stop people from abandoning homes and infecting others in a country where the majority of cases remain at large, either because clinics are full or because they are scared of hospitals regarded as 'death traps'.

A crowd attacked a makeshift Ebola quarantine centre in Monrovia on Saturday, throwing stones and looting equipment and food, and, according to one health worker, removing patients from the building.

"There has to be concern that people in quarantined areas are left to fend for themselves," said Mike Noyes, head of humanitarian response at ActionAid UK. "Who is going to be the police officer who goes to these places? There's a risk that these places become plague villages."

Aid workers say the virus reminds them of the forces roaming Liberia during the civil war, making it a byword for brutality.

"It was like the war. It was so desolate," said Adolphus Scott, a worker for U.N. child agency UNICEF describing Zango Town in the jungles of northern Liberia, where most of the 2,000 residents had either died of Ebola or fled.

Elderly people sat in the doorways of their homes, gazing at a dirt street empty but for a few roaming goats and skinny chickens, he said. "Ebola is like a guerrilla army marauding the country."

The Ebola virus, never previously detected in poverty-racked West Africa, is carried by jungle mammals like fruit bats. It is thought to have been transmitted to the human population via bush meat as early as December in remote southeastern Guinea.

Initial symptoms like fever and muscular pains are difficult to distinguish from other tropical illnesses such as malaria, meaning the outbreak was not detected until March. By the late stages of the disease, victims are at their most contagious, bleeding from eyes and ears, with the virus pouring out of them.

Countries like Uganda in east Africa have tackled previous rural outbreaks through online reporting systems and rigorous surveillance, said Uganda's Director of Community and Clinical Services Dr. Anthony Mbonye. But in the West of the continent, weak healthcaresystems were unprepared.

Liberia, one of the world's least developed nations, has poor Internet and telecommunications, and only around 50 doctors for a population of over 4 million. Traditional funerals, where family members bathe and dress highly contagious corpses, have expedited Ebola's spread to 9 of the country's 15 counties.

In recognition of the region's inability to cope, the World Health Organization this week declared Ebola an international health emergency - only the third time in its 66-year history it has taken this step.

Neighbours Guinea and Sierra Leone have placed checkpoints in Gueckedou and Kenema, creating a cross-border quarantine zone of roughly 20,000 square km, about the size of Wales, called the "unified sector".

Within this massive area, Information Minister Lewis Brown described more intense quarantine measures in Lofa county, ring fencing areas where up to 70 percent of people are infected.

"Access to these hot spots is now cut off except for medical workers," he said in an interview this week.

Reaching the sick in isolated villages there is critical because the county's main Foya health centre is full. The site was run by U.S. charity Samaritan's Purse until it pulled out after two of its health workers contracted the virus in Monrovia.

Medical charity MSF, which has now stepped in, says 137 patients are packed into the 40-bed site.

Health workers hope to train locals to create isolation units in schools and churches within their own communities.

"Quarantines expose healthy people to risk - which is why the effectiveness of states is so important in supporting preventive measures that will minimise this," said Robert Dingwall, specialist in health policy responses to infectious diseases at Nottingham Trent University.

Such measures include prevention education, crematorium facilities and protective equipment, he said.

But Liberia's response team is struggling to keep up.

The main health care centre in Lofa is "overwhelmed" by new patients, a health ministry report said. A total of 13 health care workers have already died from Ebola in the county while its surveillance office lacks computers to manage cases.

Liberia's Brown also acknowledged the risk: "We can establish as many checkpoints as we want but if we cannot get the food and the medical supplies in to affected communities, they will leave."

Even if the resources arrive, help might be chased away.

Unlike in other areas of the country, where Ebola awareness campaigns are helping to draw people out of hiding, in this isolated border region, far from the otherwise ubiquitous 'Ebola is Real' government billboards, denial is still strong.

According to a local rumour, merchants dressed as health workers are taking people away in order to sell human organs, provoking violent reactions from locals, Karbarr said.

In late July, an ambulance was stoned in the Kolahun district as it tried to take a body for burial. In the same area, a group of hand pump technicians were told to leave or have their vehicle torched. The police arrested a man this week for Ebola denial.

Brown said that people in unaffected counties in Liberia's east have so far welcomed the quarantine, but sentiment could swing if supplies start to run short.

The Italian roots of the word quarantine - meaning 40 days - refers to the isolation period for ships arriving into Venice from plague regions. But Liberia's operation could go on for three months or more, creating the need for a long-term plan.

As well as increasing the feelings of isolation and criminalisation felt by those in quarantine, the duration of the quarantine risks creating national supply disruptions. Already the price of oil and rice has doubled, residents say.

While those in Lofa are located within the country's sweet potatoes and palm fruit-growing food belt, the unaffected eastern counties cannot feed themselves.

The World Food Programme intends to distribute food to more than 1 million people living in the cross-border quarantine zone, but there are not yet plans for the unaffected counties.

"My worry is how the southeast will get food. You could have trade with Ivory coast but they might not want to for fear of the virus," said UNICEF'S Scott, referring to the landlocked River Gee and Maryland counties.

The early signs suggest this is happening already.

Aboubacar Barry, who sells rice and sugar in the Ivorian town of Danane, says his businessis a fifth of what it was before the de facto closure of the Liberian border.

Yacouba Sylla, the driver of a motorbike taxi in the border area, also complained of a slump in his business.

"Ebola hasn't arrived here, but it is going to kill us anyway before it gets here, as we will die of hunger," he said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments