Ebola crisis: How deadly is the virus, where will the outbreak spread to next – and how can it be stopped?

Cases continue to spread around the world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

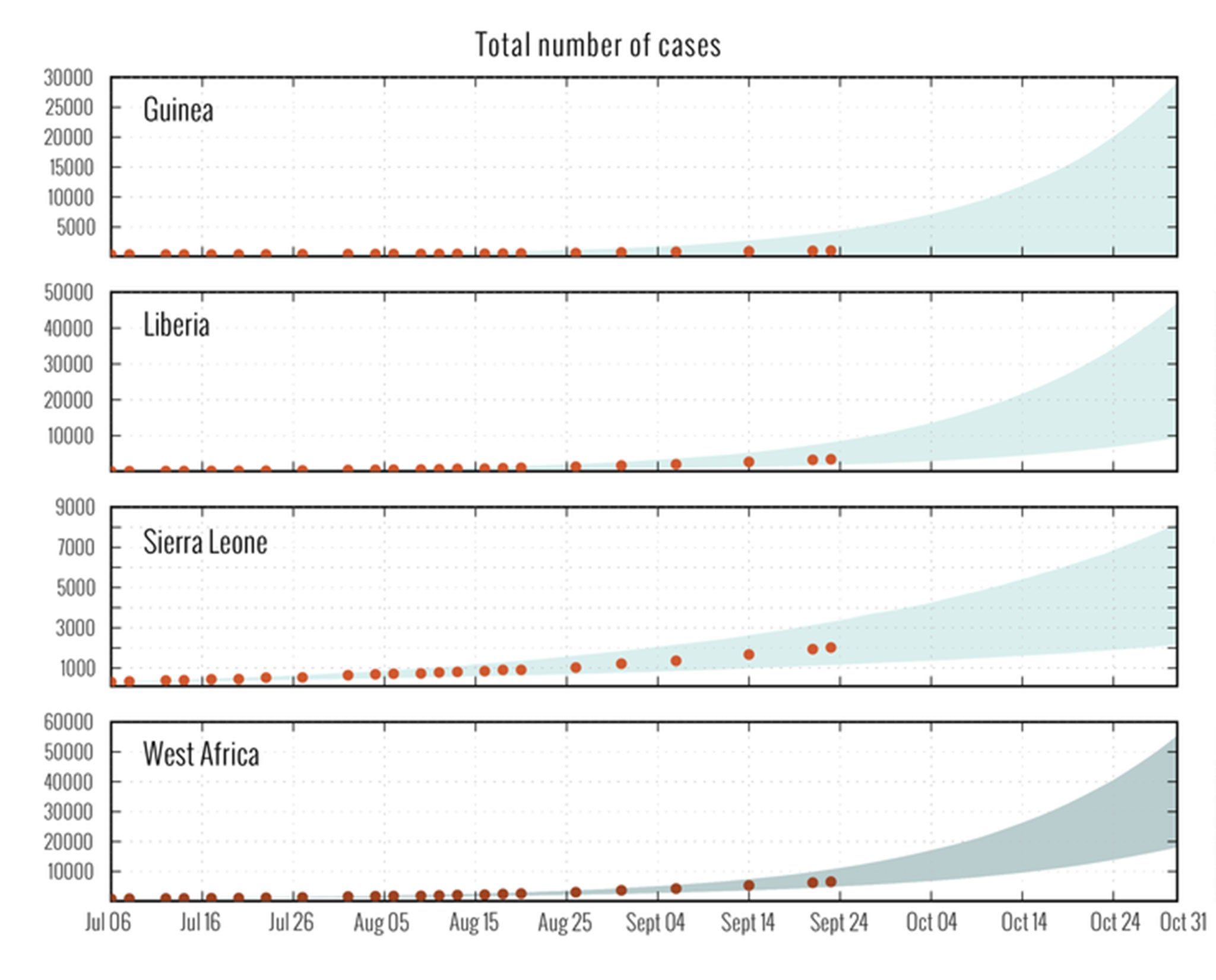

Your support makes all the difference.The world is facing an unprecedented outbreak of the Ebola virus, with more than 3,400 deaths so far and an estimated five new cases being reported every hour in Sierra Leone.

Infections and potential cases have now been reported as far afield as the Australia, Spain and the US – which this week also suffered its first death.

Philip Hammond, the Foreign Secretary, has warned that the virus will become “much more widespread” and claim “many, many more victims” if more is not done to bring it under control, and experts say we need to address the possibility of cases arriving in the UK.

But as the Government resists calls for major British airports to follow the American lead and start screening incoming passengers for the disease, just what are the risks to Britain, West Africa and the rest of the world?

Just how deadly is the Ebola virus?

The strain of the Ebola virus involved in the current outbreak in West Africa has a mortality rate of 50 per cent – though rates for the outbreaks since 1976 have varied from 20 to 90 per cent.

The disease was at its deadliest when it was first discovered – in part at least because no one knew the best way to deal with it.

Since then, we have developed strategies of barrier nursing, quarantine, protective equipment and contact tracing – and we know that these are enough to contain outbreaks if they are employed early enough.

That’s because of the way Ebola is spread. Though highly contagious if it is given the chance to enter the body, it can only do so through the direct transferral of bodily fluids such as vomit, sweat or blood – making it much easier to contain than air-borne viruses like avian flu.

Click to enlarge | Infographic by statista.comThe reason the current outbreak has become so vast is simple – it was left unchecked for at least three months before being reported to the World Health Organisation.

The fact that it has been allowed to get a major foothold in West Africa – sprouting up in countries without the medical infrastructure to deal with it – is the reason it has become such a deadly prospect there.

But there is no risk of something similar happening in the UK, Europe, the US or anywhere where systems of isolation and treatment are more established and – now – alert to the danger.

Where will it spread to next?

While we know how to stop Ebola from killing more than a handful of people if it is caught early, now that there have been more than 7,000 cases reported in West Africa it is inevitable that some cases will be carried further afield.

Dr Edward Wright, a senior lecturer in Medical Microbiology at the University of Westminster who has been working to develop harmless versions of viruses like Ebola for the past 10 years, admits that “we have no experience of dealing with anything like this before”.

He says that it is “likely” Ebola will arrive in the UK, but that it is almost impossible to predict a precise timeframe – or even a particular point of entry.

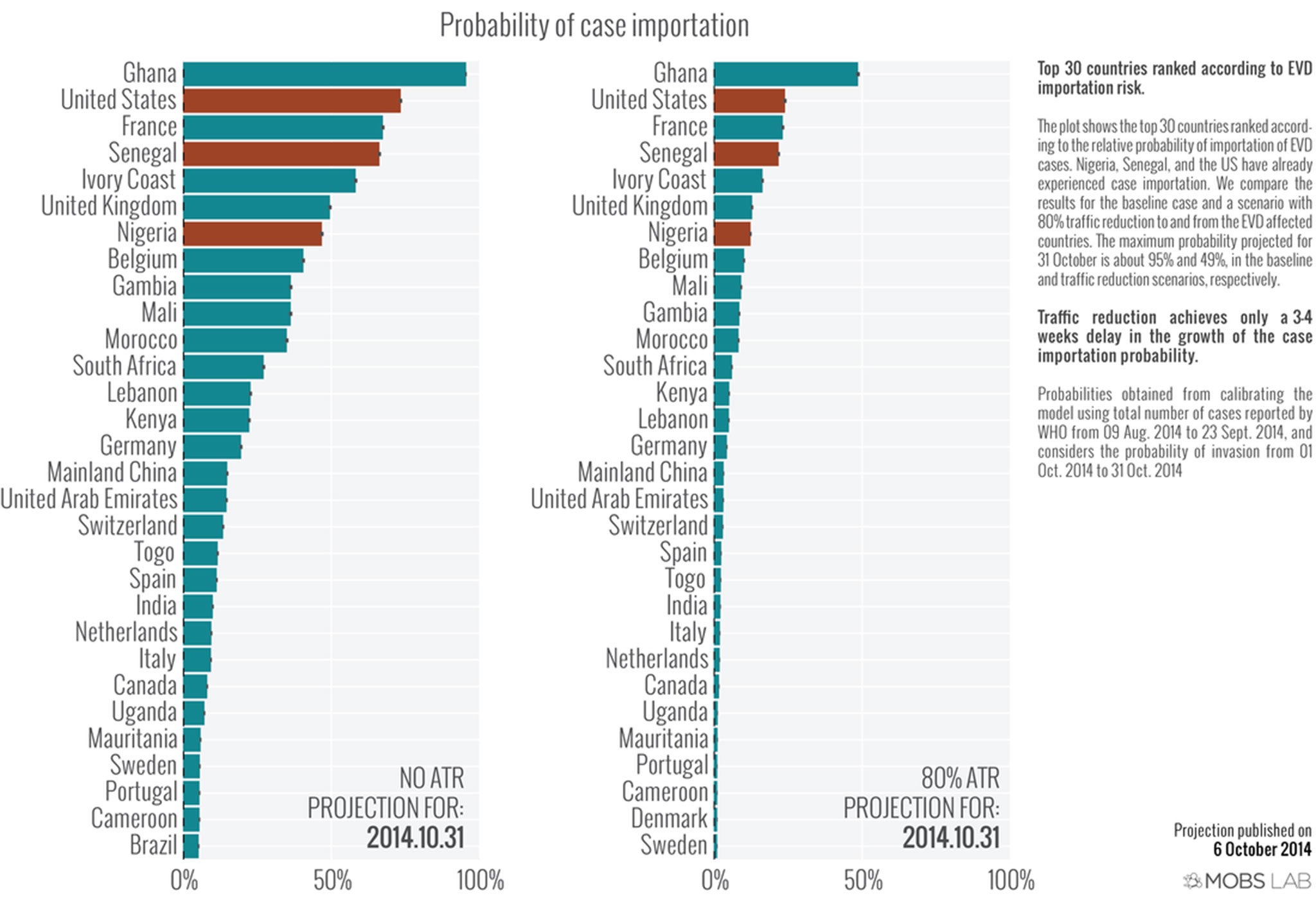

“A US university said that based on global travel patterns and London being a hub for international flights, there is a 15 to 50 per cent chance of a UK Ebola case by the end of this month.

“But that same report said on 23 September that there was a 10 per cent chance of a case in the US – and on 24 September Thomas Duncan arrived from Liberia carrying the disease.

“I think it is likely there will be a UK case – but it’s very difficult to predict when or even where.”

Dr Wright says that, now that cases have been confirmed in the US and Spain, outside Africa the UK is the next country after France in terms of the most likely places the disease will spread to next.

“It’s right to be concerned about this,” Dr Wright says, adding that a strong level of public awareness is “a very strong way to limit the disease’s impact”.

“But our Government has been fortunate in that we have had several months to prepare and put in place the necessary measures – and from what I’ve seen they have been put in place – so that we can deal with these cases when they arrive,” he says.

How can it be stopped?

The reason Ebola has been able to spread from the affected region in West Africa – and one of the reasons why screening on arrival at UK airports would probably not be effective – is that the disease has a relatively long incubation period.

A recent study by the New England Medical Journal found that the average time it takes between infection and the appearance of symptoms is 11 days – though experts say it can range between four days and a number of weeks.

“There is definitely a concern that people can get further in that time,” Dr Wright says – pointing out that Thomas Duncan “felt fine for three or four days” after he arrived in the US from Liberia.

He says that the issue of the disease spreading within Spain to a nurse only highlights the dangers faced by health workers – the body carries an exponentially increasing amount of the virus up until the point of death – rather than a concern for the general public.

“What is promising is that in Nigeria a man flew in with Ebola, developed symptoms there, the virus was passed on to 19 other people – and then it was controlled using basic prevention strategies.”

But while we can be confident about stopping outbreaks outside West Africa, Dr Wright says the disease has likely got beyond the point where traditional strategies alone can stop the virus in the affected region – and that’s where vaccines and drugs come in.

Dr Wright is one of a number of scientists around the world working on producing a drug that can provide antibodies to help fight the disease, similar to the ZMapp treatment already being used in a limited number of cases.

But he says that we are some way from making these widely accessible, and that a more likely solution will be the rolling out of a vaccine for health workers – potentially as early as the start of next year.

Three weeks ago, Sarah Gilbert and a team at Oxford University started human trials on a vaccine developed from a virus that originates in chimpanzees.

After a series of high profile UN and WHO meetings, the regulations governing their research and that of a similar team in the US have been fast-tracked, meaning they will be allowed to carry out a limited roll-out if the data from the first phase of their research is positive.

“From speaking to Dr Gilbert, we can say they are anticipating this end data by the start of December,” Dr Wright says.

Ultimately, the only way to stop Ebola cases emerging around the world is to tackle it at source in West Africa. Britain has just sent around 750 soldiers and officials to help bolster the infrastructure required – and Dr Wright says “feet on the ground” is probably the best way we can help tackle the disease right now.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments