Censored 16th century anatomy textbook could be root of vagina taboo

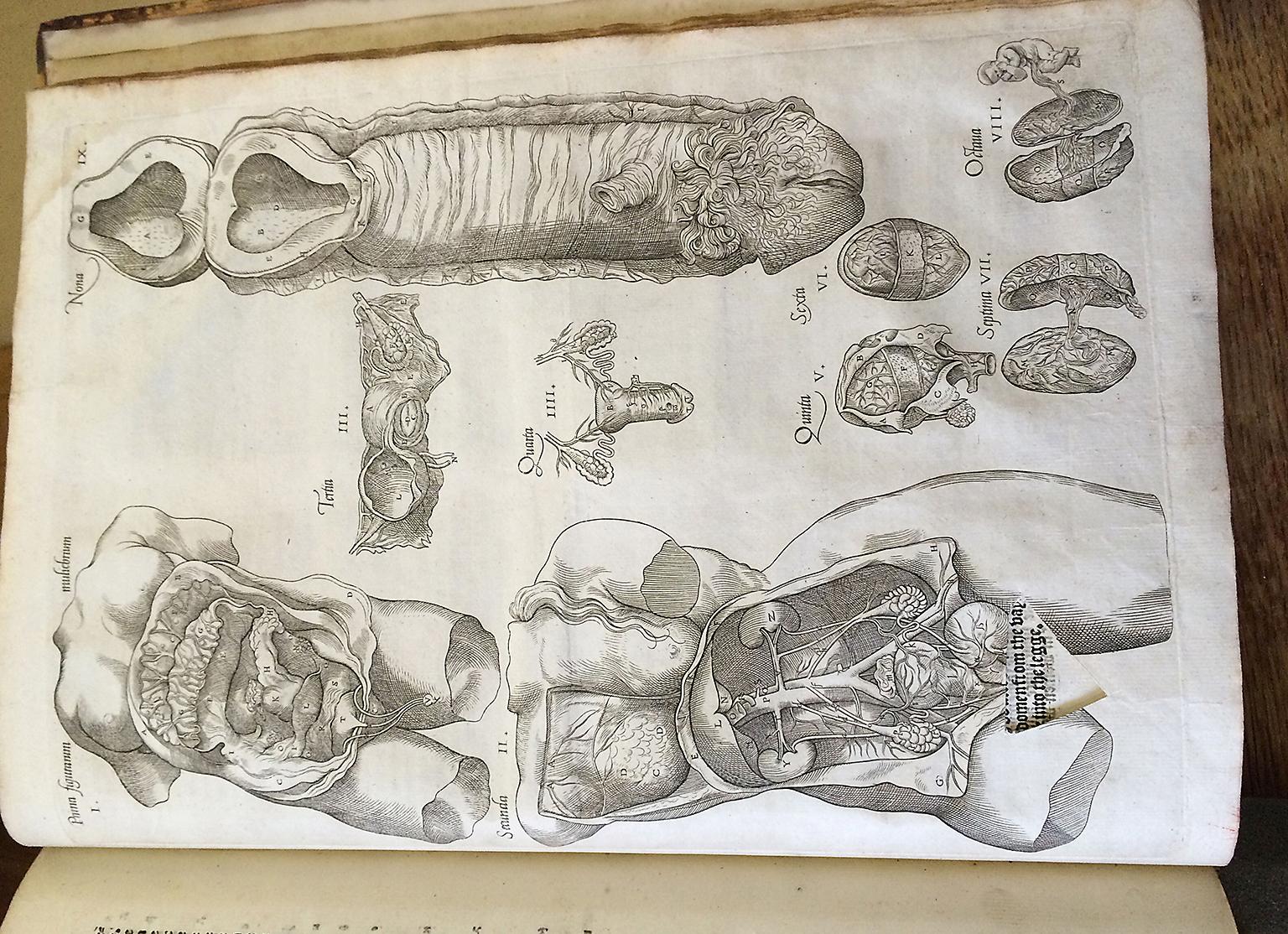

The book's original owner has cut away a neat triangle of paper on which the vagina would have been drawn

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A censored 16th century anatomy book may provide evidence that taboos slowed the development of knowledge of the female genitals, researchers have said.

The 1559 edition of Thomas Gemini's Compediosa Totius Anatomie Delineatio features a depiction of a semi-dissected female torso, and the book's original owner has cut away a neat triangle of paper on which the vagina would have been drawn.

It will be displayed in an exhibition at St John's College at the University of Cambridge, and curator Shelley Hughes said it may offer clues as to why knowledge of the female anatomy lagged behind that of the human body as a whole.

She said the book's original owner was “disturbed by its depiction of a semi-dissected female torso. We know this because the offending part, a neat triangle of paper on which the vagina would have been drawn, has been carefully cut away.”

She added: “Sin and female flesh were held in close association in 16th century society with naked women often portrayed as the servants of Satan. Perhaps Christian Europe would have to overcome its shame over the female reproductive organs in order to discover more about their structure.”

Before the 16th century, many European academics believed that female genital organs were simply lesser versions of male organs, turned inside out.

This dated back to classical medical authorities such as Galen in the 2nd century, who had been prohibited by law in Ancient Rome from cutting up human corpses.

The 16th century was a time of medical revolution, with pioneering researchers such as Andreas Vesalius challenging accepted views on anatomy, with evidence gathered from human dissections and direct observation experiment.

But there was still a reluctance to take on some foundational beliefs in science.

The display shows how an evidence-based knowledge of the structure of the body emerged as superstitious and religious barriers weakened.

The exhibition, to be displayed on Saturday, is called ‘Under The Knife At St John's: A Medical History Of Disease And Dissection’

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments