The Austerity Issue: don't panic

Amid the bewildering complexities of the global financial crisis, one simple fact stands out: the little we have left needs to go a lot further. Fear not! We'll show you how to endure the forthcoming recession with a bit of grit, some nous and the wise advice of our post-war forebears. And you never know, you might have a laugh or two along the way... To begin our special issue, a celebration of the true heroine of austerity Britain: the housewife

We are living on the cusp of unprecedented times – or unprecedented for the past half-century, anyway. Of course there has been the odd painful blip, such as the oil shock of the mid-1970s or the quite sharp recessions of the early- 1980s and early-1990s, but broadly speaking the pattern has been one of growing prosperity and an ever-rising standard of living. Now, in a mood of palpable apprehension, we face something perhaps entirely different. But there are lessons we can learn – the lessons of austerity Britain.

"No sooner did we awake from the six years' nightmare of war and feel free to enjoy life once more, than the means to do so immediately became even scantier than they had been during the war," lamented Anthony Heap, a local government officer living near St Pancras, London, in his diary at the end of 1945. "Housing, food, clothing, fuel, beer, tobacco – all the ordinary comforts of life that we'd taken for granted before the war, and naturally expected to become more plentiful again when it ended, became instead more and more scarce and difficult to come by." Little did he, or anyone else, imagine the hard, stony road that lay ahead. It would be another nine years before rationing was finally ended in 1954, nine long years of attritional discomfort and privation.

Rationing and shortages affected almost every area of everyday life. Coal, petrol, cars, clothes, footwear, furniture, bedding, toys – all were hard to come by, being either strictly rationed or near unobtainable. "The greatest disaster is the inability to buy a handkerchief if one has sallied forth without one," bitterly complained one middle-class housewife to the research organisation Mass Observation; another objected that the fuel shortage "entails poor lighting on railways, in waiting rooms etc, with consequent eye strain and depression". But for most people, there was during these bleak years one supreme, overriding obsession: food.

Rose Uttin, a Wembley housewife, listed in December 1947 the miserable state of play in a diary kept for for Mass Observation: "Our rations now are 1oz bacon per week – 3lbs potatoes – 2ozs butter – 3ozs marge – 1oz cooking fat – 2ozs cheese & 1s meat – 1lb jam or marmalade per month – lb bread per day." And, she added forlornly: "My dinner today 2 sausages which tasted like wet bread with sage added – mashed potato – tomato – 1 cube cheese & 1 slice bread & butter. The only consolation no air raids to worry us." Some four years later, with the Tories returned to power after defeating Clement Attlee's Labour government, the ' new prime minister asked his Minister of Food to show him an individual's rations. "Not a bad meal, not a bad meal," Winston Churchill said when the exhibit was produced. "But these," nervously explained the minister, "are not rations for a meal or for a day. They are for a week."

Not surprisingly, the nation grumbled. "Oh, for a little extra butter!" wailed Vere Hodgson in west London in her 1949 diary, just after it had been announced that the meat ration was to go down again. "Then I should not mind the meat. I want half a pound of butter a week for myself alone... For 10 years we have been on this miserable butter ration, and I am fed up. I NEVER enjoy my lunch..."

The housewives, responsible every day for putting food on the family table, were on the front line, among them Judy Haines of Chingford. "This shopping!" she exclaimed in her diary in 1946 after a wonderful set-piece account of the sheer time-consuming tensions and frustrations involved in trying to procure a rabbit from her local butcher. "All housewives are fed up to the eyebrows with it."

It was not a situation that brought out the best in everybody. "Considering the rationing of the people she certainly looked well fed," rather unkindly reflected Mary King, a retired teacher in Birmingham, after the visit of the Queen (the future Queen Mother) to that city in November 1945, while the following summer, when Mass Observation asked people in Chelsea and Battersea whether they would be willing to give up some of their food for those starving in Europe, the reply of one working-class woman – "I wouldn't go short on half a loaf to benefit Germany" – was all too typical.

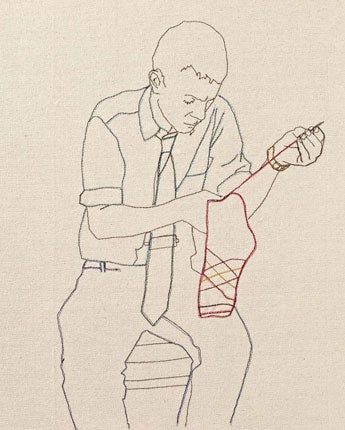

Even so, what I found striking – and reassuring – as I went through the diaries and other contemporary records was the extent to which people, above all women, simply got on with things, often through the application of much resourcefulness. "The ration this week, of chops, contained some suet," noted Haines soon after VE Day. "Good! Chopped it and wrapped it in flour for future suet pudding." Or take the equally indomitable Marian Raynham in Surbiton on a Wednesday in July 1947: "Had a good & very varied day. Went to grocers after breakfast, then on way home in next door, then made macaroni cheese & did peas & had & cleared lunch, then rest, then made 5lbs raspberry jam, got tea & did some housework, listened to radio & darned... In bed about midnight."

For many, whether they liked to admit it or not, part of the coping involved a covert use of the black market. Here there was a fascinating change of attitude as the dreary years went by. At first, as a legacy of the war, the general sense of a shared national purpose, involving equality of sacrifice, meant it was demonised, along with the spivs who ran it, even if sometimes there was no alternative but to use it. But by the late-1940s, as the peacetime rationing and shortages continued interminably and that sense of shared purpose waned, so the spiv became an increasingly acceptable figure – epitomised by the rising variety and radio star, Arthur English, "The Prince of the Wide Boys", with his white suit, huge shoulder pads and flowery kipper tie. "Sharpen up there," ran his catchphrase, "the quick stuff's coming," and a weary nation at last found something funny in austerity.

Two fundamental, timeless lessons emerge from the whole experience. First, that most people will broadly accept straitened times if they are genuinely convinced of their necessity and that there is no alternative. Second, that social cohesiveness during such an unwelcome turn of events will rest to a large degree on the extent to which the pain is administered on an equitable, transparent basis. Even so, should the economic downturn prove severe, it is still likely to be a psychic shock for anyone under, say, the age of 40, for whom the austerity years are not even a folk memory. The process will be a huge challenge to the legitimacy of our democratic political system, though not inconceivably may do wonders to strengthen and reaffirm that rather frayed legitimacy.

Personally, I have one modest hope. Snoek (pronounced "snook") was a vaguely mackerel-type South African fish imported in huge quantities in 1947-1948 by the Ministry of Food and given a huge publicity campaign, including a recipe for a concoction to go with salad immortally called snoek piquante. So disgustingly dry and tasteless did almost everyone find it, however, that millions of tins were left unsold, eventually used as pet food. Should snoek make a comeback, I would welcome the chance to try it – once, anyway.

'Austerity Britain, 1945-1951', by David Kynaston,is published by Bloomsbury at £25

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks