My summer of doom: From horrible jobs and broken hearts to a brush with death, four writers remember the year it all went wrong

The worst job ever

By Katy Guest

Fifteen-year-old Brooklyn Beckham was justly praised a few weeks ago for getting a job in a coffee shop instead of living off his parents. Lucky him. For students in the 1990s, paid work as rewarding as serving coffee was impossible to find, which is how come I spent my summer holidays from Cambridge University ironing Sisyphean piles of tablecloths in a hotel laundry in Plymouth, and scrubbing mould off slippers in Derby.

These, however, were Pulitzer-level tasks compared with the worst summer job in the world: selling roses in the bars and clubs of the West Country. Yes, reader, I was that idiot in the smock who interrupted your fun evening to try to flog you a wilting flower out of a bucket. I'm sorry. I had to do it, to buy books.

It was a good summer in 1994, but I lived mostly by night. Each Thursday, Friday and Saturday afternoon, a mini-van would come to collect young women from our houses, already dressed in our uniforms: a tubular piece of floral cloth with elastic around the top and a pinny around the middle, which made sexual harassment so much easier for the drunken punters. (You try holding your clothes on when you've got a bucketful of soggy flowers in one hand and a bag of money in the other.) I know that men applied for the jobs, too – my boyfriend and brother did – but somehow they never made it to the interview process.

We were driven to rose-selling HQ, off an A-road just outside the very middle of nowhere, and were assigned our area and driver for the evening. Those who got Torquay would whoop. The less proficient sellers were sent to Truro. That summer, I got to know Truro's grottier nightspots very well. Not surprisingly, many girls blew their puny wages on amphetamines to see them through to the next day, when they'd finally be driven home.

For each rose sold for £2, we received 20p – though if I had 20p for every man who asked me for sexual services in return for his purchase, I could have quit in July. Many lost their rag when I explained that I was a rose seller, not a prostitute. Many more told me, sulkily, "Cindy always used to do it." But the mythical Cindy (not her real name) had apparently run away to join the circus after one golden summer of rose-sales supremacy.

I did once agree to eat a rose for a man who bought two, and ate the other himself. I tucked the petals into my cheek and spat them out in the ladies', but the girl who got Truro the following week never forgave me for setting the precedent. One colleague dined out on the story of the Bristol Ritzy nightclub, where she had interrupted a guy in the middle of receiving a… Cindy Special… and persuaded him to dig his hand in his pocket for two quid. His friend carried on. She deserved more than flowers.

I finally quit on the last day of my vacation, when the boss asked me retrospectively to sign a contract waiving his responsibilities for tax and National Insurance contributions. I was driven home in disgrace. It was a learning curve, but the smell of roses still makes me feel sick.

The bad romance

By Rosamund Urwin

I met him in the summer term of my first year of university, on the sticky dancefloor of a nightclub affectionately known as Filth. I had drunk so many WKD Blues that my tongue was the colour of cornflowers, and my sense of judgment long gone. I was smitten – so smitten I ignored a mutual friend's warning that he'd just come out of a relationship. The next night, we went home together.

Alex, as he wasn't called, was two years older than me, witty, sophisticated and smart. I fell in love with him instantly; he was a modicum above indifferent to me. Whenever I saw him, I felt the butterflies of cliché, but with a dull ache behind them too – the knowledge that the egg-timer on our relationship was already turned over and when the sand ran out, he'd leave.

It was supposed to be a summer of Pimm's, punting and garden parties – Brideshead Regurgitated. Instead, it was three months of being strung along and of rapid weight gain as I ate my feelings. There was one warm night – lying in the grass on the cricket pitch together, laughing over our inability to identify anything other than Venus and Orion – where I felt euphoric, sure I was winning him over at last. But then I waited five days for the next text message, with only the verdant stains on my skirt reassuring me that it hadn't all been a dream.

I became the Helena to his Demetrius, a pathetic spaniel who couldn't pull away. Eventually though, in a nightclub, I found the strength to tell him to "give a fuck or fuck off". He claimed he cared, but I'd put my handbag down to make my demand, and someone stole it. The bouncer (who may just have been a sadist) told me that thieves often dump bags in sanitary-towel bins. So I sat in the ladies' rifling through them, one hand mummified in loo paper, the other holding my nose. It wasn't there, so I was forced to wait until the club closed, sobering up as everyone snogged drunkenly around me. Alex had gone home at the first mention of a lost bag.

Somehow, we made it to the end of term. Alex was going to Italy but promised to call on his return. He didn't, of course. The kindest way to break up with someone is the swift approach, like ripping off a plaster. Instead, I was given the slow peel: left in limbo and allowed to hope that he'd just been hit by a truck rather than the infinitely worse scenario in which he simply didn't love me.

My 19th birthday came and he didn't call. He didn't even ring to break up with me when he promised he would. So by the time we spoke in mid-August, I was on holiday with my parents. I remember standing in the rain in a Cornish car park as my heart was pulverised. I pretended it was amicable, but was secretly hoping he'd catch gonorrhoea in a public loo. The rest of the summer was spent moping and writing lousy heartbreak poetry, the kind that reads like bad U2 lyrics.

When we returned for the new term, I pretended not to care. Then Alex kissed another girl in front of me, and it wasn't so much salt in my wound, as sulphuric acid.

The nightmare tour

By Rhodri Marsden

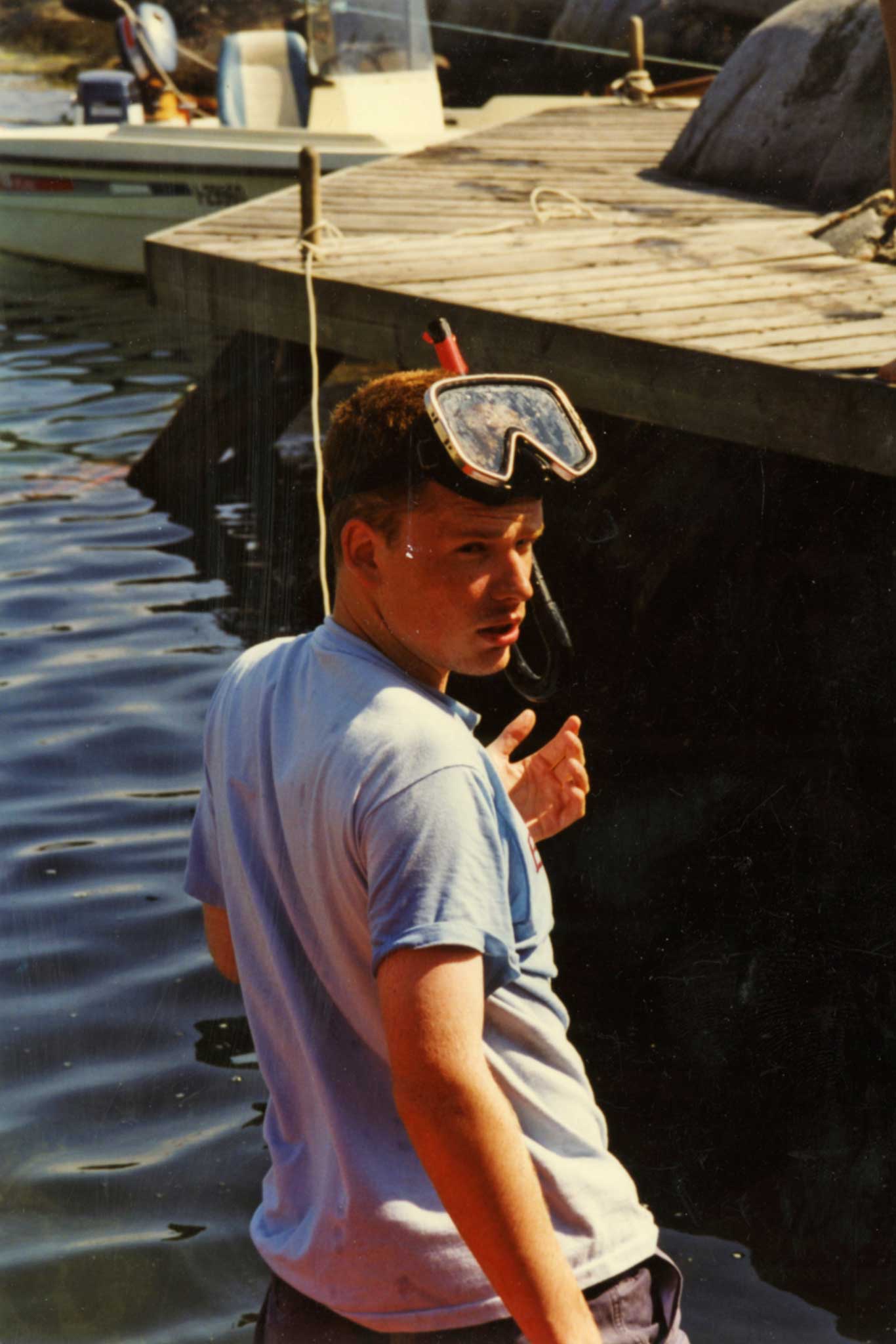

I dreamt of rock stardom, but the summer of 1991 put paid to all that. The idea of spending July and August touring Europe for the first time with my band, the Keatons (below, with Marsden centre), playing our painstakingly crafted brand of high-concept indie rock (ie a noisy shambles perpetrated by drunk men) held great appeal. But those weeks were strewn with scenes of high drama and abject misery, beginning on day one when our singer decided he didn't want to go. We went anyway. I was obliged to sing, not because of any natural charisma but more because I knew all the words. We set off in a rusting heap of a van with no wing mirrors and an old sofa chucked in the back. It was driven by a friend of a friend who we later realised was a porn addict with unpalatable views on immigration. Within 15 minutes the back door had fallen off and we'd run out of petrol on the outskirts of Welwyn Garden City.

We ran out of petrol a lot, because money was scarce. We had pooled all our spare cash to get us on to the ferry in the desperate hope that the gigs would pay enough money to get us back home again. Meals were skipped and considerable weight was shed, although there always seemed to be enough cash for cigarettes, which I, as a non-smoker, deeply resented. It was a hot summer, and the van came to resemble a large stove full of rotting humans belching noxious fumes. Every night someone had to sleep in this foul ashtray to ward off potential burglars – as if continental thieves would be remotely interested in our equipment, which only worked sporadically and was largely held together with gaffer tape.

We traversed the continent subsisting on a constipation-inducing diet of bread and cheese and leaving a swirling vortex of bad feeling in our wake. We depended on the kindness of strangers for hospitality, and showed our appreciation by breaking things and leaving a rancid smell. The driver became ever more erratic and unpleasant, culminating in a furious physical altercation between him and me on the hard shoulder of a motorway outside Reutlingen. The gigs themselves were beyond chaotic; in Paris we played a squat that was more like a building site, and mid-song I received a powerful electric shock that left me lying on the stage in tears. In Maastricht we had to play instrumentals only as we'd offended the man who was supposed to lend us a PA. A gig in Perigueux was stopped by the police for excessive noise. On the one occasion where the band was vaguely impressive, a girl called Frederika gave me her number but I lost it in a hedge.

We rounded off the tour by breaking down on the Paris ring road in rush hour. As we were ferried to safety in a police van, our bass player tried to lighten the mood by offering a gendarme a copy of our latest EP. The look of contempt on his face summed up the way an entire continent evidently felt about us. It was a sobering moment. We did go on tour again, but that summer taught me to expect the worst, and be relieved when things turned out to be merely dreadful.

The holiday disaster

By Mike Higgins

It was when I saw Jo floating, face down, unconscious in the water beneath a low midnight sun that the night quickly turned dark. But let's go back to the start of that evening in late July, the end of our week-long holiday: I can't recall what we had to eat, but I do remember someone had made vodka jelly, and boy was that going down easily after plenty of wine. But the setting was enough to get you tipsy: a tiny, rocky island half a mile off the coast of Sweden, deserted except for one low wooden house, no electricity, no hot water, no phones and the seven of us, in our mid-twenties, lolling about under the Baltic sun.

It was 11pm before someone, inevitably, suggested we all take a dip. And still light enough for us to pick our drunken way 50 yards across the island's tumble of steep, sharp rocks to the boulder we liked to jump from. What could go wrong in that apparently endless twilight? So in we went, of course, naked, one after the other, over and over. Until I saw Jo, vomit bubbling up around her hair, drifting away so prettily. I jumped in, and dragged her back to shore, the others by now aware that Jo had passed out in the water. As people say, you sober up instantly in moments such as these. Except you don't. You're just scared as well as hammered.

Did I check Jo's pulse? I don't know. But she was moaning as I cleared vomit from her mouth. Still half-conscious, she bit down hard on my fingers. Around me, unlikely rescue plans were hatched about how to get Jo back to the house – we were in no state to carry her. "I'm gonna get the motorboat," shouted Harry, who could stand, but only just. "No you're f*****g not," someone shouted more loudly. Harry stayed put. The late hour decided that argument – it was gone midnight, and too dark for any boat, and cold too. So Maggie decided to get blankets and clothes – except that as she scrambled up a steep rock, she lost her footing and fell back about five feet, on to her shoulder, with a horrible crack. Nothing was broken, it seemed, but with another person down came the realisation that we were almost too drunk to help one another.

"Where's Ben?" said another voice out of the gloom. Gone to get some hot drinks someone thought, though how would those drinks get back across that field of boulders? Another person appeared with blankets for Jo, and Maggie volunteered to sit with her until dawn. I stayed with them for a bit, then I returned to the house not long after the others. My girlfriend told me they had returned to fumes of gas, and Ben passed out on the sofa with a cup of tea in front him.

Appropriately enough, the sun didn't rise the following morning as we waited for a taxi boat to take us back to the mainland. Shame and hangovers thickened the atmosphere. Jo, at least, was back in the house, conscious but speechless. Maggie was moving gingerly. All eyes were downcast. Each time Ben went looking for forgiveness, his girlfriend hissed that she was not speaking to him. It wasn't yet August, but there was more than a hint of autumn in the air.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks