Love story: Jan Morris - Divorce, the death of a child and a sex change... but still together

Nearly 60 years ago, the writer James Morris married Elizabeth Tuckniss. Their relationship endured divorce, the death of a child – and his sex change. Now they have cemented their partnership with a civil union

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

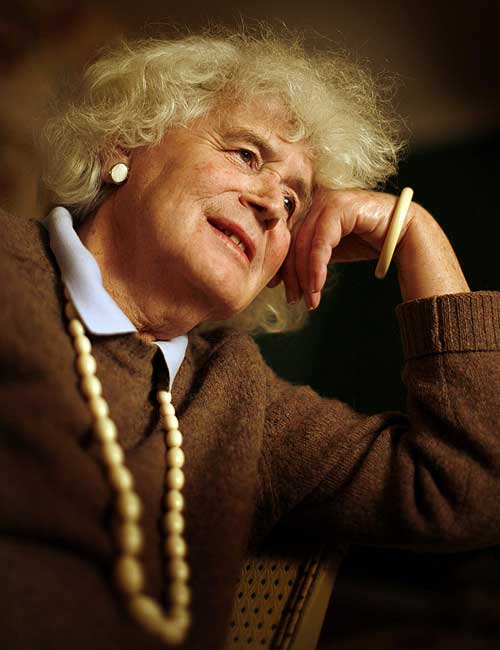

Your support makes all the difference.James Morris was one of the most successful young journalists of the Sixties generation; Jan Morris is one of the finest travel writers and historians in Britain. Now, late in life, Jan (formerly James) has gone through a civil ceremony with the woman he married nearly 60 years ago.

But then, Jan would say, nothing important changed in their relationship except that detail she refers to as ,"this sex-change thing – so-called". Their enduring partnership is perhaps one of the most remarkable of modern times.

The first time that Elizabeth Tuckniss walked down the aisle, in 1949, her groom was a dashing undergraduate. This month, her civil partner was an elderly lady recently voted the 15th greatest British writer since the war.

In reality, the couple have never been apart. In a touching story of constancy, they stayed together after Morris's trip to Morocco in 1972. He went as a man, and came back as woman. The law, then, did not allow same-sex marriages, so the couple were obliged to go through an amicable divorce. Morris used to describe her as her "sister-in-law", but on BBC Radio 4's Bookclub yesterday, she revealed that the relationship was closer and more enduring than that implied.

"I haven't told this to anybody before," she said, "I've lived with the same person for 58 years, I married her when I was young and then this sex-change thing – so-called – happened and so we naturally had to divorce, but we've always lived together anyway. I wanted to round this off nicely so last week Elizabeth and I went to have a civil union."

The ceremony was held at the council office in Pwllheli on 14 May, in the presence of a couple who invited them to tea at their house afterwards.

"I made my marriage vows 59 years ago and still have them," Elizabeth told the Evening Standard. "We are back together again officially. After Jan had a sex change we had to divorce. So there we were. It did not make any difference to me. We still had our family. We just carried on."

The ceremony was "quite private" and "very nice". They had to read out a promise to each other, which was probably superfluous after so many years. They then signed their names, and were offered tea or biscuits. The only ominous detail was a small notice, in standard use at civil ceremonies, which warns that this is a legal proceeding, and giving false information is an offence.

More than half a century ago, James Humphrey Morris was the most famous newspaper journalist in Britain. He was assigned by The Times to cover John Hunt's expedition to Everest in 1953, a job that required physical fitness and courage. It also led to a comic conversation with the Queen, at a meeting in Buckingham Palace of representatives of the British Book World many years later, which Jan Morris told to The Independent.

She asked the Queen: "Do you remember when they climbed Everest for the first time, and the news came to you on the day before your coronation?"

"Yes, of course I remember," the Queen replied, to what she obviously thought was a foolish question.

"Well," said Jan, "I was the person who brought the news back from Everest so that it got to you on time."

This left the bemused Queen wondering how this grey haired woman, or any woman, could have been the first with such dramatic news. Morris watched her reaction.

"Her eyes went cold," she said. "I felt sorry for her because she always has people to explain things, and there was nobody around to put her straight. She suddenly found herself in totally unknown territory."

Even before the Everest trip, James Morris had had a varied life. There was a Somerset childhood, a Welsh father and an English mother she has never discussed, boarding school in Lancing College, where the boy became convinced that he was in the wrong body – not homosexual, just "wrongly equipped".

Then there was a brief spell as a cub reporter in Bristol, military training at Sandhurst, and service as a teenage intelligence officer with the 9th Queen's Royal Lancers in the final throes of the war, which took him through Italy and Palestine. Demobilised in 1949, he went to Christ Church College, Oxford, to read English, and in the same year, married the daughter of a tea planter from the island then known as Ceylon. She has said that she "always" knew of her husband's belief that he should have been born female. It did not stop them having five children, one of whom died at the age of two months.

In 1960, he published a cultural history of Venice, which established him as a major writer, and which has never been out of print. Its success brought in enough money for a switch from journalism to writing books full time. She has published about 40, including the trilogy, Pax Britannica, about the rise and fall of the British empire. It was begun when she was a man and completed when she was a woman, in 1978. Morris regards that as her best work. There was also a satirical novel, Our First Leader, about an independent Wales established after a Nazi invasion, and dozens of highly regarded and widely read travel books.

The trip to Morocco in 1972 was possibly the bravest thing the former James Morris ever did. Doctors warned him that a sex change could have unforeseen effects upon his personality and literary talent, but he defied them and started taking female hormones during the early 1960s, and finally had surgery at the age of 46 in Casablanca. She described the transition in the 1974 book Conundrum, the first book she published under her new name.

Such open discussion of what was then a very unusual operation created waves of social embarrassment and unwanted publicity. She once wrote: "I do not doubt that when I go, the event will be commemorated with the small back-page headline 'Sex Change Author Dies'."

The television interviewer Alan Whicker said later that he did not know whether to shake her hand or kiss, to offer to buy beer or cucumber sandwiches. There was an infamous television interview in which Robin Day tried to ask her whether she was having a "full sex life". She was furious, and complained to the director general. He later admitted that he had found it all excruciatingly awkward.

However, she gave herself the best advice on how to deal with life's irksome problems, in her autobiographical book Pleasures of a Tangled Life. Travelling, she wrote, "can be done well or badly, conscientiously or with a slovenly disregard of detail and nuance". Doing it well means putting up with irritants like being overcharged or robbed, because the miseries of travel are "the salt that gives them flavour".

Jan and Elizabeth have been together now for just under half a century, with most of those years spent in the Welsh village close to where Jan's father grew up. They have specified that when they die, their headstone will say, in Welsh and English: "Here are two friends, at the end of one life".

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments