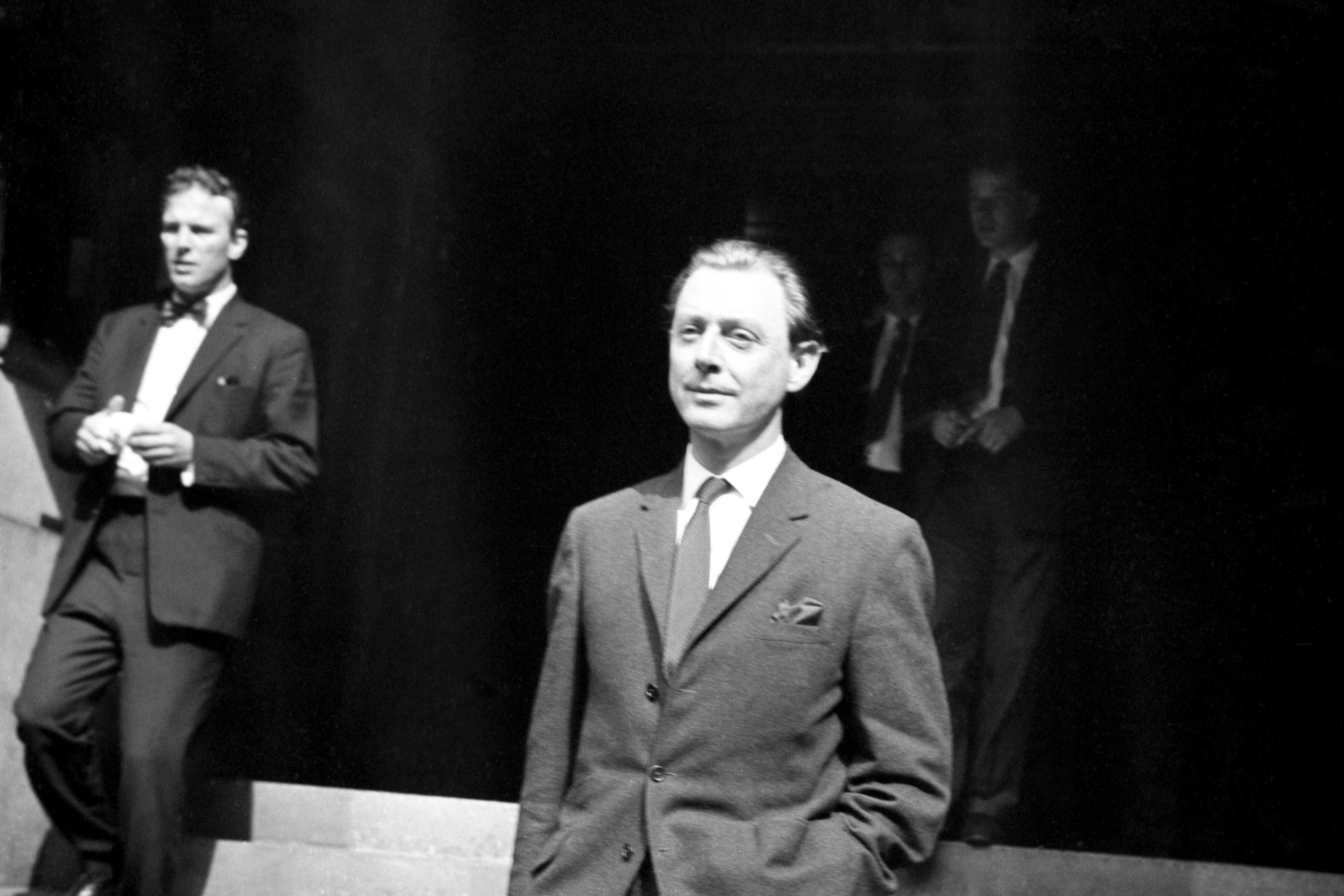

Society artist Stephen Ward felt he was ‘being assassinated’ in Profumo scandal

Newly-released MI5 files give an insight into Ward’s state of mind, in a situation where some have claimed he was made a scapegoat.

The society osteopath and artist involved in the Profumo affair told how he felt he was “being assassinated” in the midst of the sex and spies scandal which engrossed 1960s Britain.

Stephen Ward was convicted of living off the immoral earnings of prostitutes, but died before he could be sentenced, having taken a drug overdose during his trial.

The scandal had centred on John Profumo, Secretary of State for War, who lied in the House of Commons about having an affair with former showgirl Christine Keeler.

The revelation ended the minister’s political career and was seen as the catalyst which would bring about the downfall of the Conservative Government soon after.

Ward had introduced Keeler to the politician, who resigned after claims she had also slept with Russian intelligence officer Eugene Ivanov, at the height of the Cold War.

A newly-released batch of MI5 files give an insight into Ward’s state of mind around that time, in a situation where some have claimed he was made a scapegoat for his role in the scandal.

He wrote to then-Opposition leader Harold Wilson from prison to plead innocence two months before killing himself, documents show.

The handwritten letter, on Brixton Prison notepaper and dated June 1963 to then-Labour leader and future Prime Minister Mr Wilson complained of untrue claims against him that “gravely affect my present position”.

In the letter – among a release of documents newly-digitised by the National Archives – Ward rejected the suggestion he had been a “Soviet intermediary” in his dealings with Ivanov, or that he had asked for a police inquiry into the matter to be called off.

There can be no hope of the truth ever coming out if these and comparable errors are allowed to stand uncorrected

He said comments about him in Parliament had been “most unfair and prejudicial to my legal position”.

Ward wrote: “May I appeal to you earnestly to look into these matters which gravely affect my present position.”

He added: “There can be no hope of the truth ever coming out if these and comparable errors are allowed to stand uncorrected.”

An MI5 report dated May 1963, noted that a source who visited Ward thought him to be “ill-at-ease” and possibly “not far from a nervous collapse”.

In a conversation with the Prime Minister’s Principal Private Secretary, the documents show, Ward told him “if you were in my position you would feel as if you were being assassinated at this moment”, adding that the situation was “bad” and that the stories in the newspapers were “not quite the truth”.

In 2017, the Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) said it had found no evidence the prosecution was politically motivated, but that had Ward lived, he could have sought to challenge his conviction at the Court of Appeal on other grounds.

It said there was “considerable force” in the argument that prosecution witness Keeler’s subsequent conviction for perjury and possibly prejudicial media coverage at the time of Ward’s trial could have affected the safety of the conviction.

The documents, released by the National Archives, are available to view in digitised form at www.nationalarchives.gov.uk.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks