Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This year’s general election was the most unfair to voters in Britain’s history, according to an analysis by an electoral group.

A new report by the Electoral Reform Society found that the result was "the most disproportionate in history" compared to the votes actually cast.

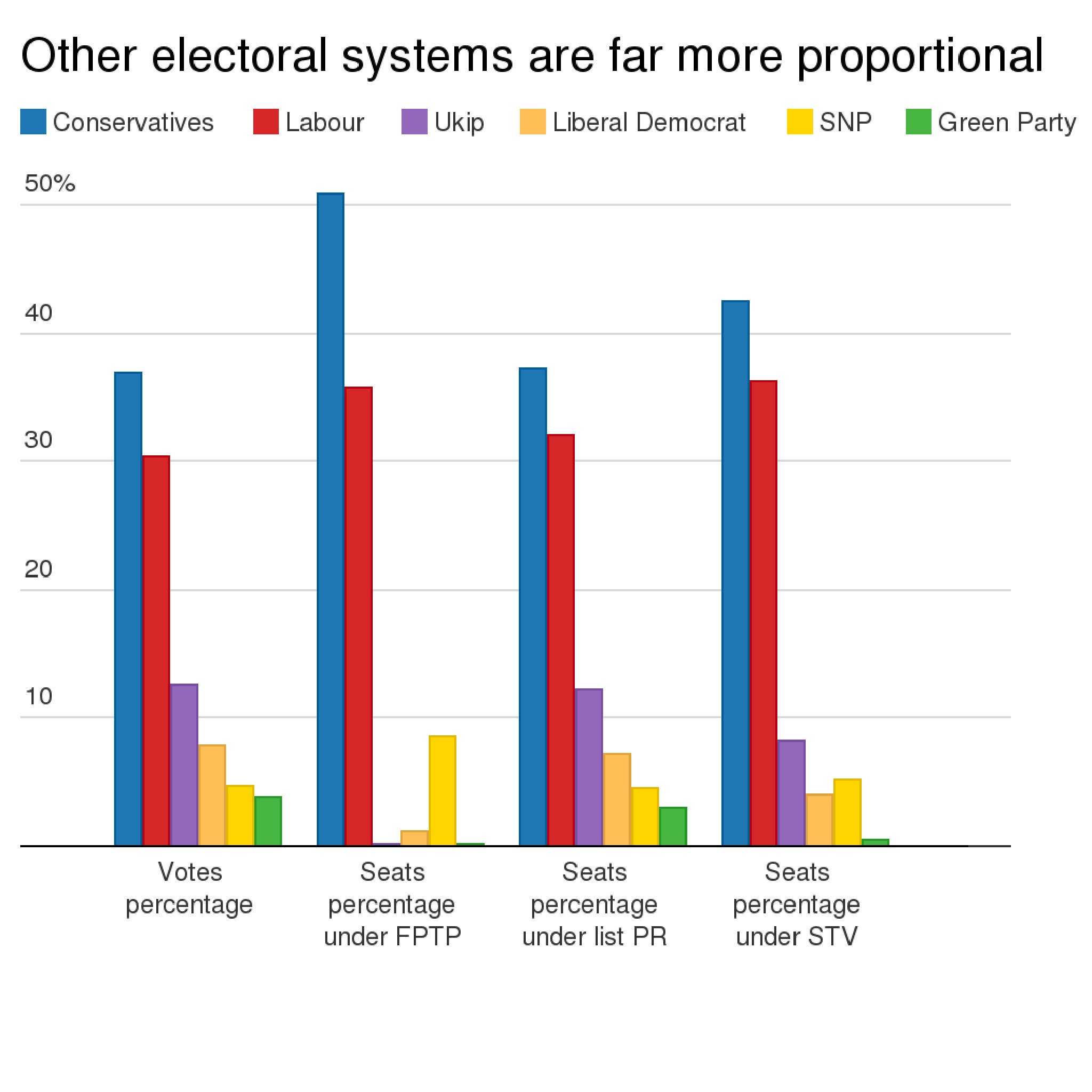

The chart below gives us a clue: for a variety of reasons FPTP doesn't translate votes into seats in a proportional way, and we didn't really get the parliament we voted for.

When looking at the overall result, not every vote is equal under Britain's electoral system, because so many voters are cast in areas where candidates do not win.

These votes are "wasted" and don't count towards the final result, which leads to huge disproportionality and a wonky looking result.

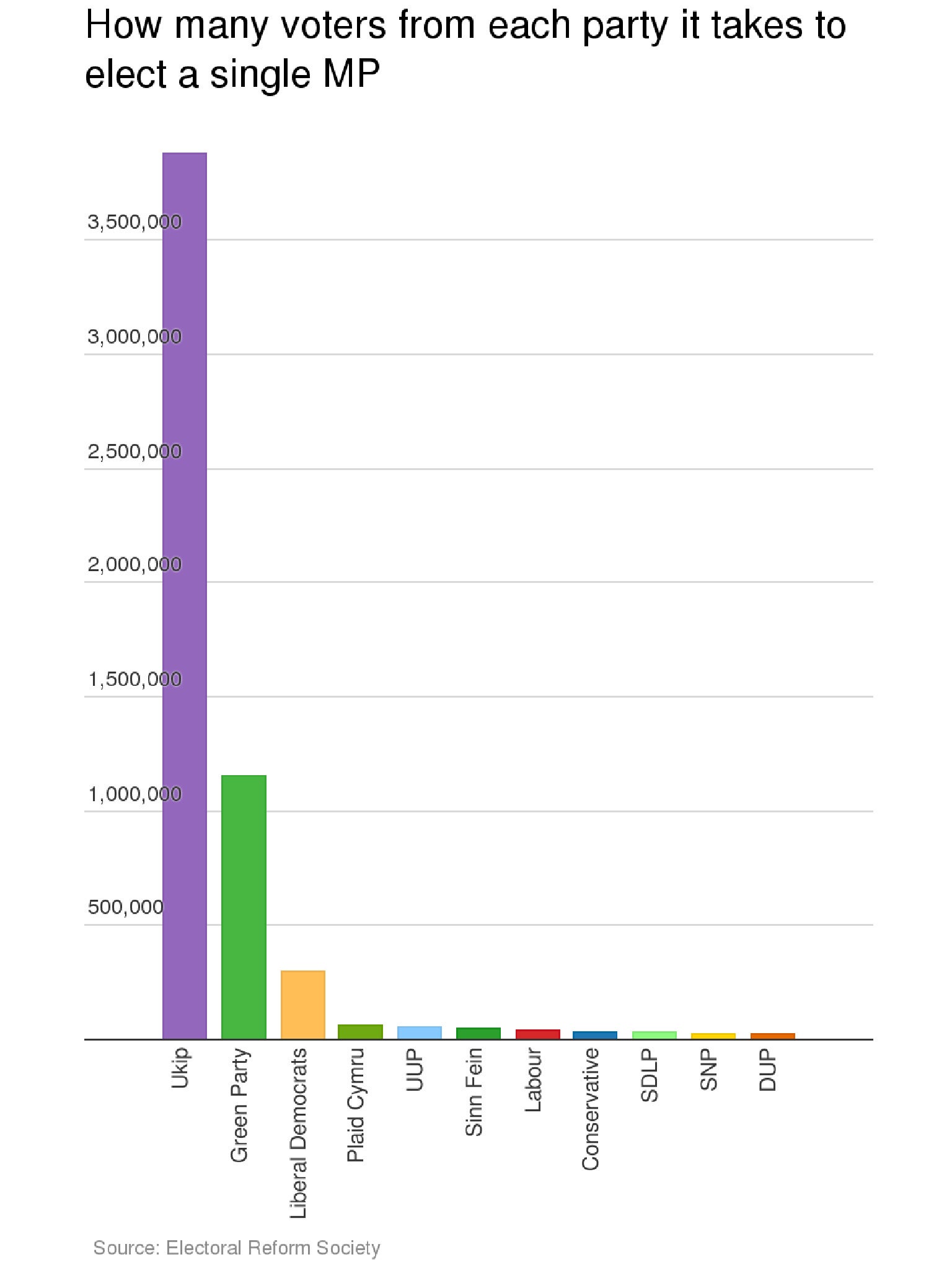

The effect of this disproportionality is most striking when stated in terms of how many voters from each party it takes to elect an MP.

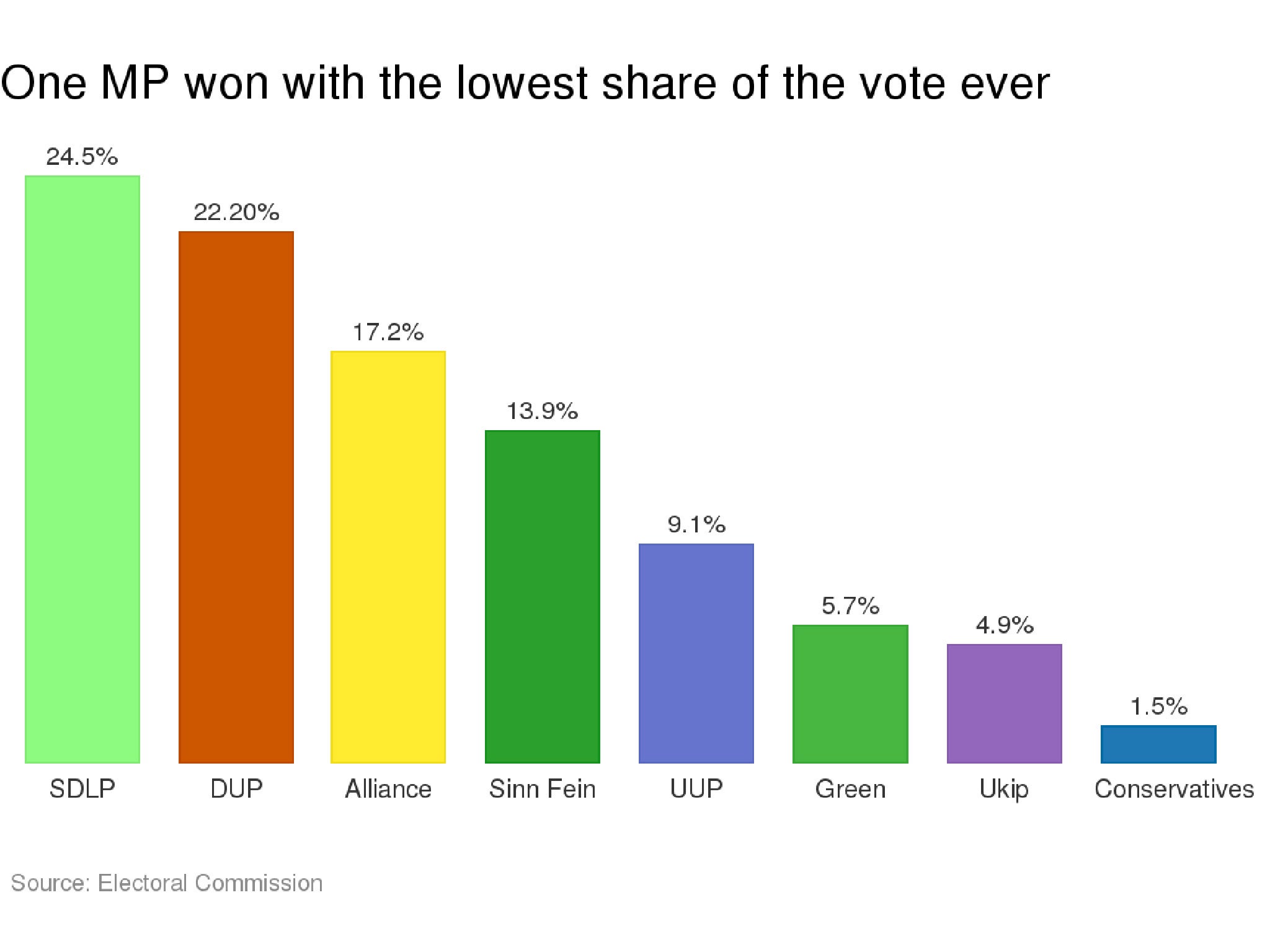

The constituency of Belfast South in Northern Ireland is a good example of the problem.

So many parties were competitive in the area that the vote ended up being split between them all, with six different parties getting more than five per cent of the vote - and four more than ten per cent.

As a result the area's MP Alasdair McDonnell, of the Social Democratic and Labour Party, won the seat despite receiving just 24.5 per cent of the vote.

This is the lowest share ever obtained by a winning candidate in a UK general election ever: 75.5 per cent of the MP's electorate didn't vote for him, but because 2 per cent more voted for him than the DUP candidate he still wins.

If this happened to the same extent all over the UK, 75 per cent of votes would be completely ignored in the result. In reality, the same effect did happen everywhere, to a slightly lesser extent.

The good news is that Britain doesn't have to use First Past the Post. Most European countries use more proportional electoral systems which are just as simple to use but produce much fairer results.

One option is list proportional representation, which produces highly proportional results but forces people to vote for parties rather than candidates. This variant is common across Europe and counts votes using the d'Hondt method, named after a Belgian mathematician.

Anther option favoured by British reformers is Single Transferable Vote. STV, which is already used in local government elections in Scotland and is favoured by the Electoral Reform Society and the Liberal Democrats, produces broadly proportional results, but keeps the link between voters and their local MP.

It works by using large multi member constituencies and ranking candidate in order of preference. Results are proportional within constituencies but the nationwide result can be slightly distorted - though nowhere near to the extent of our current system.

The chart below shows how the results the different systems would produce, according to the Electoral Reform Society's poll.

Reform could be a long time coming, however. The two biggest parties do very well out of the current system and have historically sought to block any attempt to change their privileged position.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments