Schools concrete crisis: A timeline of crumbling infrastructure, chances missed and warnings ignored

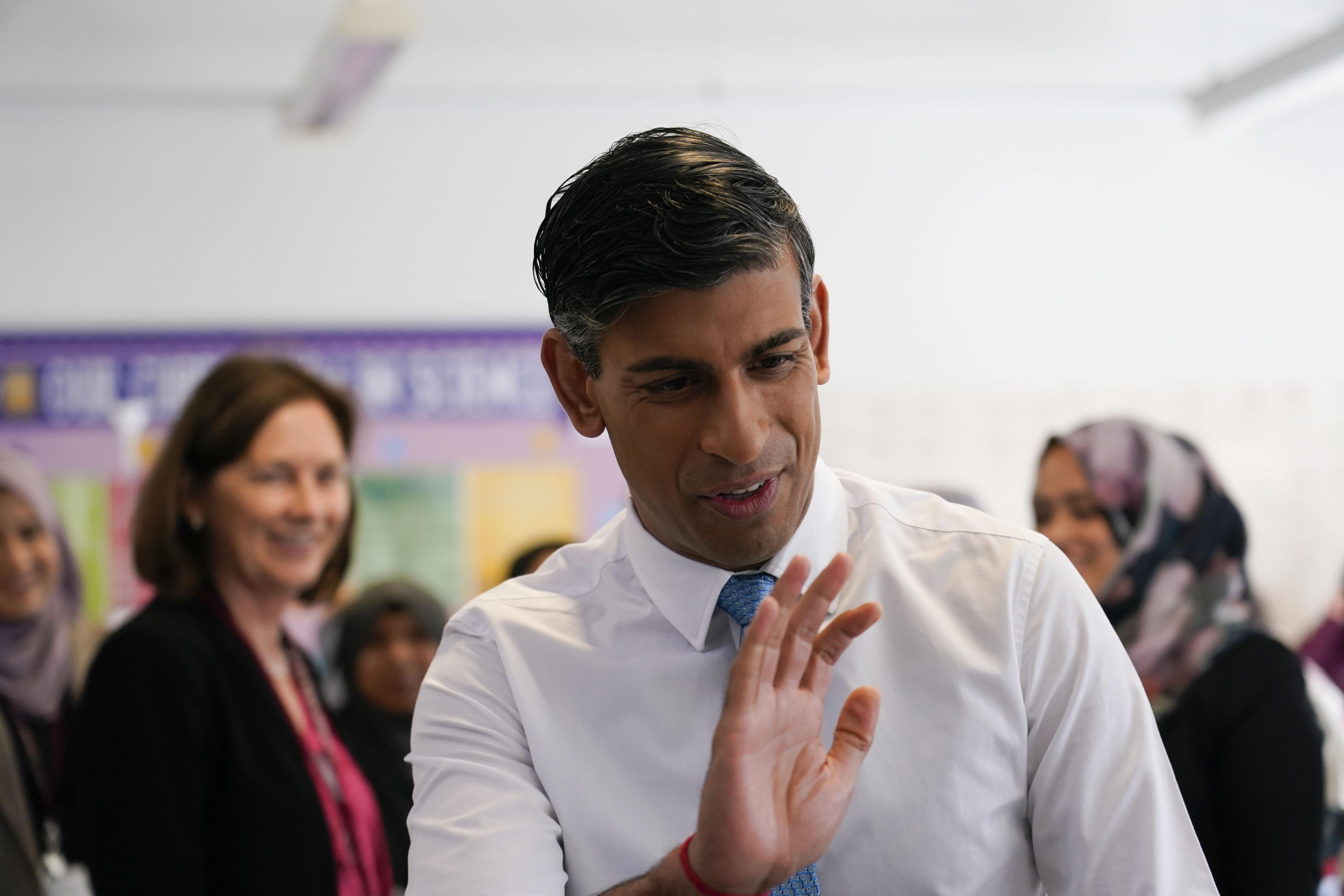

‘Cowboy builders’ Rishi Sunak and Gillian Keegan under fire as government publishes list of 147 institutions of concern over the use of sub-standard material in their construction

Rishi Sunak’s government is under intense pressure to act as the crumbling concrete crisis leaves Britain’s schools in a state of disarray just as the new academic year gets underway, with more than 100 institutions forced to shut either partially or entirely over safety concerns.

Education secretary Gillian Keegan has provoked further ire by telling school leaders to “get off their backsides” and address the structural problems their institutions face from the historic use of reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (Raac) in their construction, a material now considered unsafe, while headteachers have accused the government of “dumping” them with the issue after years of neglect.

Geoff Barton, head of the Association of School and College Leaders, told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme on Wednesday that it would take 440 years to fix the issues in Britain’s schools under Mr Sunak’s plan to rebuild 50 per year, which has so far seen only four refurbished in the last two years.

He also accused Ms Keegan’s predecessor Michael Gove of “gleefully” scrapping Labour’s £55bn Building Schools for the Future programme during the David Cameron years, which would have refurbished 700 schools but was rejected as too costly in favour of the Conservative’s own (cheaper) Priority Schools Building Programme.

The situation, Mr Barton said, had left “headteachers scrambling around trying to identify bits of concrete that might look like Aero bars when they should be focusing on children’s learning”.

New defence secretary Grant Shapps also warned that Raac will be found in “virtually all” public sector estates, with the same concerns also likely to apply to the material’s use in nurseries, colleges, hospitals and care homes.

The government then published a list of 147 schools believed so far to be affected, just ahead of Prime Minister’s Questions in the House of Commons, where Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer likened his opposite number to a “cowboy builder” and said the fiasco was the “inevitable result of 13 years of cutting corners, botched jobs and sticking plaster politics”.

Here’s a timeline of how Raac came to be so widely used across the British construction sector and what warnings were issued when.

1950-79

Raac, a steel-reinforced version of the autoclaved aerated concrete that was first developed in Sweden in the 1920s, begins to be used as standard in the construction of public premises during the rebuilding boom that followed the destruction wrought by the Second World War.

The material was regarded at the time as a cheap, lightweight, fire-resistant alternative to conventional concrete with good thermal properties and was widely adopted for use in new schools, hospitals and offices

1980-2000

Problems with Raac begin to become apparent over the course of the 1980s, with multiple roof collapses resulting from corrosion reported at around the time the material’s approximate 30-year lifespan expired in some of the earliest buildings erected since the war.

Demolitions are carried out in some cases while inspectors deem the steel reinforcement beams used in many instances to be inadequate.

In 1996, UK government body the Building Research Establishment (BRE) publishes a paper in which it warns that Raac roof planks are particularly prone to weaknesses like deflections and cracking and should not be used in future construction.

2002

A further BRE report reiterates the danger inherent in older buildings in which Raac is found to be present.

2017

The Standing Committee on Structural Safety (SCOSS) is asked to investigate the suitability of the material.

2018

A flat roof built using Raac at Singlewell Primary School in Gravesend, Kent, suddenly collapses in July. Fortunately, no one is hurt as the accident occurs at the weekend when no pupils or staff members are on site, although computers, toilets and furniture are damaged.

That December, the Department for Education (DfE) and the Local Government Association urges schools to check their roofs, walls and floors “as a matter of urgency”, stating that the Gravesend case had proved that the old assumption that visual evidence of deterioration was sufficient warning “could no longer be relied upon”, given that the collapse happened less than 24 hours after the first signs of stress were noticed.

2019

The SCOSS issues a safety alert on the failure of Raac planks in May and recommends that all installed before 1980 should be replaced “as they are now past their expected service life”.

2021

Another classroom ceiling collapses in November, this time at the private Rosemead Preparatory School in Dulwich, London, during a handwriting lesson with teacher Margaret Rautenbach and 15 of her Year Three pupils, who were treated in hospital for injuries ranging from fractured limbs to heavy bruising and left shaken by the experience.

“There was a huge noise, suddenly, like a thunderous kind of noise”, Ms Rautenbach says afterwards. “The whole ceiling appeared to be flashing with lights, and we saw the roof just about to fall on top of us.”

One mother says her daughter “looked like a zombie from a horror movie” when she was rescued from the rubble.

The Thurlow Educational Trust, which administers the school, is subsequently fined £80,000 and its chairman Nick Crawford states that the institution has “taken significant steps since the incident to ensure that its health and safety arrangements are as robust as they can be”.

The DfE publishes a guide for schools on how to spot deteriorating Raac, advising them to look out for a “bubbly” appearance and report any such citings so that inspectors can be called in to investigate.

2022

The DfE sends out a questionnaire to all responsible educational bodies, asking them for more information to help understand the extent of Raac’s use in schools across the country.

An inspectors’ report in November meanwhile identifies structural concerns at three primary schools in West Lothian – Knightsridge Primary in Livingston, Our Lady’s in Stoneyburn and Windyknowe Primary in Bathgate – causing pupils to be relocated and the council to approved £10m in funding for the repairs the following February.

2023

Seven education unions demand urgent action over the “shocking state” of school buildings at the risk of collapse at a time when teachers are already at odds with the DfE and staging strikes over pay.

By May, the DfE identifies 572 schools in England that might contain Raac and therefore represent cause for concern but admits a further 8,000 educational sites still need checking.

A month later, the DfE tells four schools in Essex and the north east of England to close and teach pupils remotely or relocate them elsewhere after Raac is discovered in their ceilings.

Just days before the beginning of the new school term in September, the DfE announces that 104 schools and colleges will need to partially or fully shut down buildings because of the risk posed by Raac.

A number of education unions come together to put their names to an open letter to the government demanding answers in which the signatories write: “Our members are managing the anxiety of parents and carers on behalf of government. The least they are entitled to know, with confidence, is how they ended up in this situation when the government knew of the risks long ago.”

The row then deepens as the scale of the problem becomes apparent, with NHS England calling for an urgent review of its hospitals, the head of the National Audit Office adding his voice to the criticism of the government’s approach to repairs and Ms Keegan antagonising headteachers and being accused of “finger-pointing”.

Mr Sunak finds himself forced to defend 13 years of Conservative leadership that appears to have taken little action after becoming personally embroiled when a former civil servant at the DfE tells the BBC the now-PM had known about the need to rebuild between 300 and 400 schools a year during his tenure as chancellor of the exchequer.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks